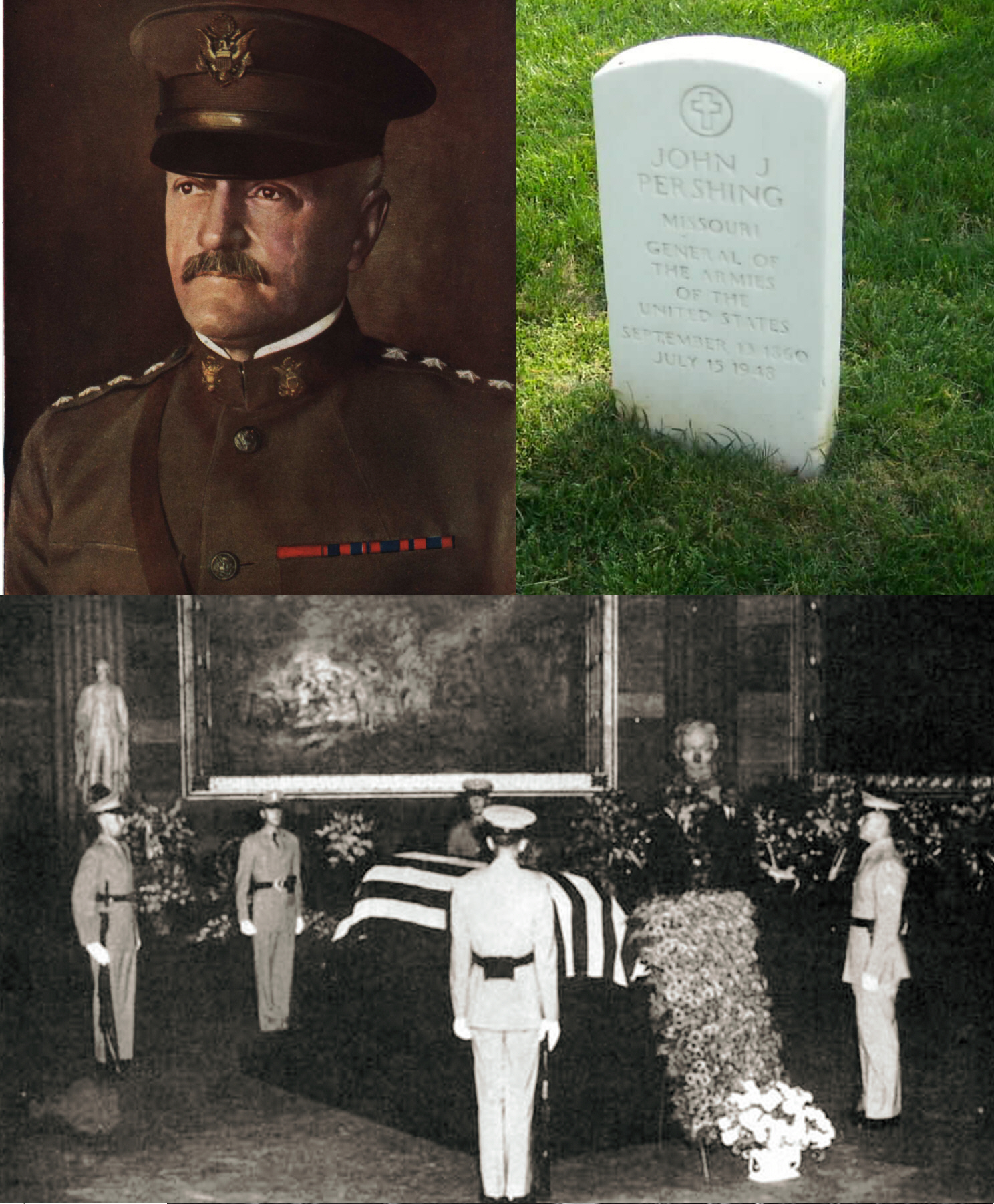

The name Passchendaele has become synonymous for waste of life and pointless orders to continue the attack irrespective of the ground conditions.

Tony Noyes, Battlefield Guide Par Excellence and Friend

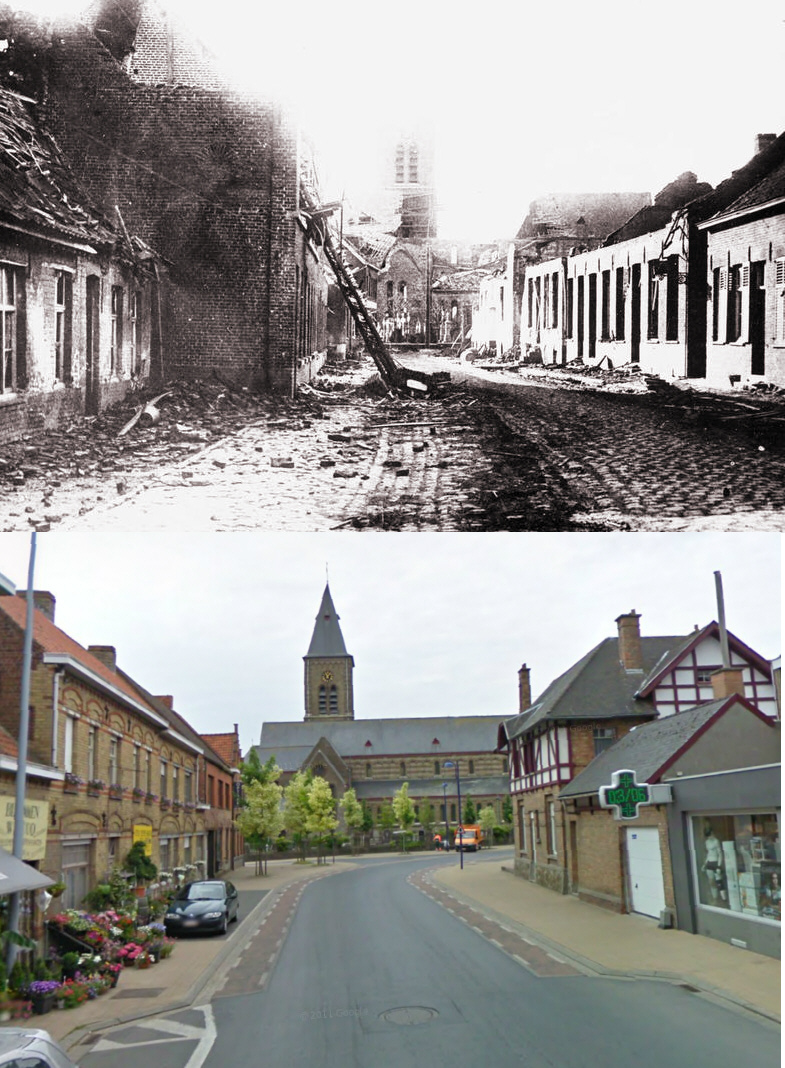

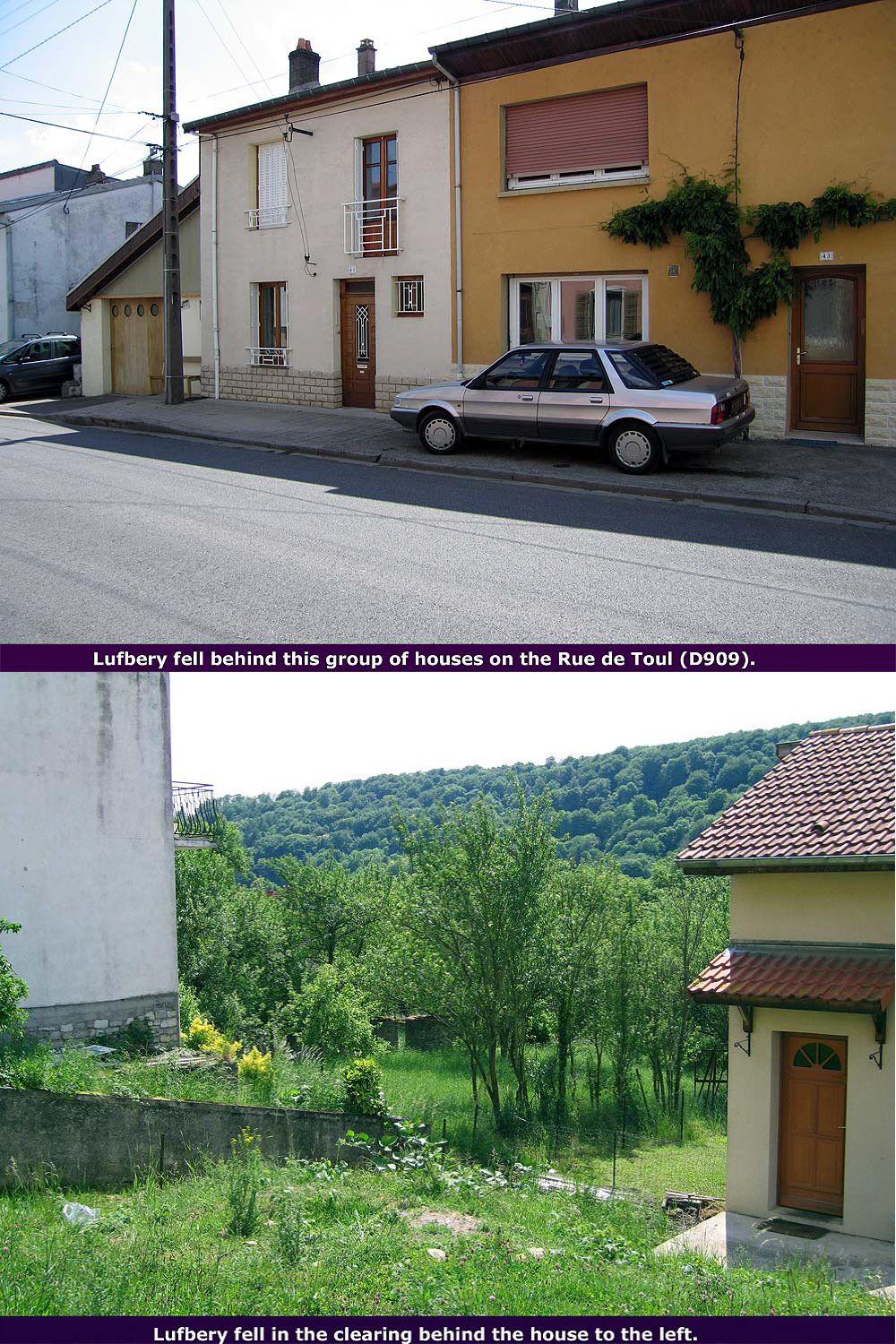

Pilckem Ridge Area: When the Rain Began and Today

Click on Image to Expand

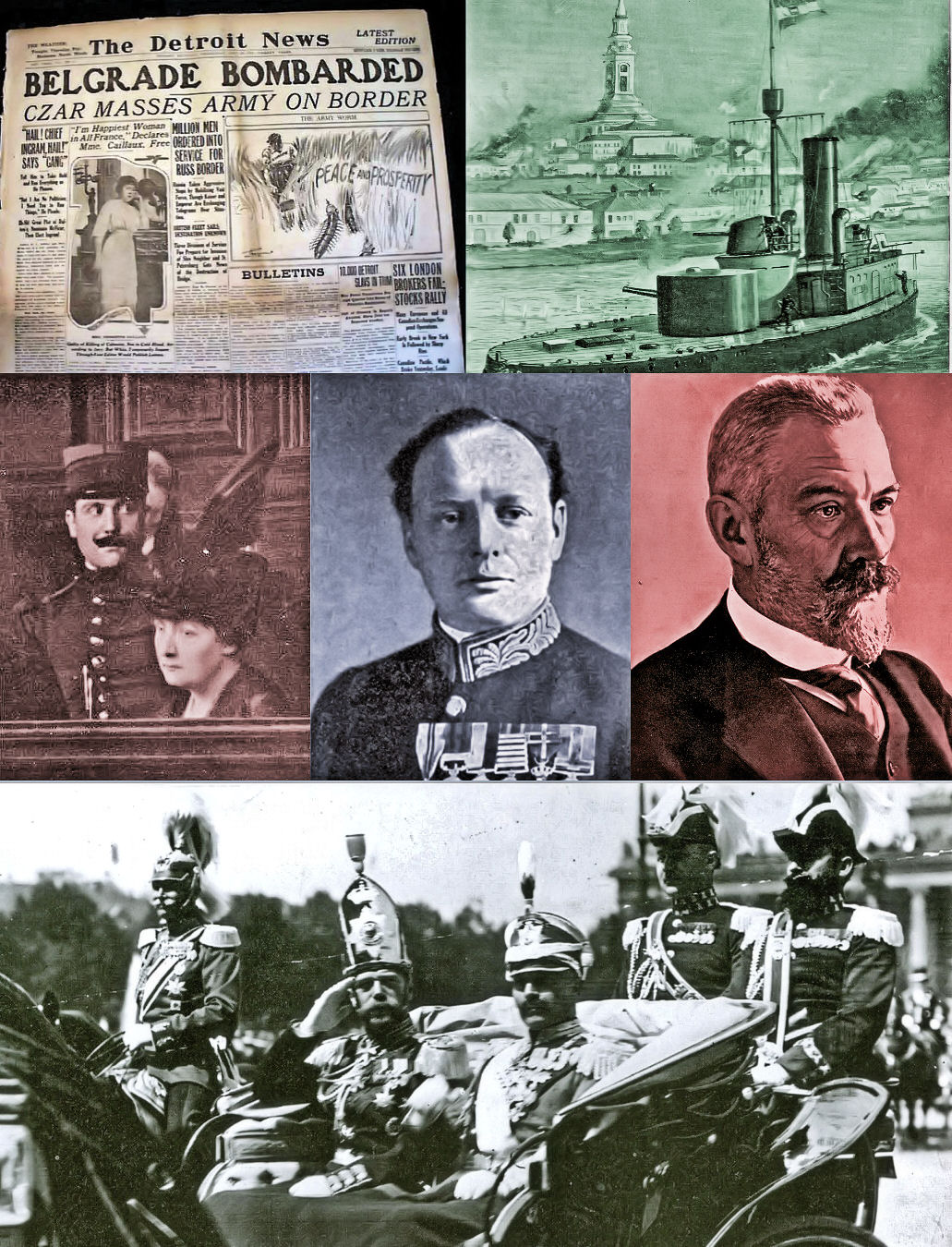

The horrendous losses to the French in their part of the Allied offensive of April 1917 had led to widespread mutinies during the summer. As a result, the

burden of continuing the attack on the Germans in the fall of 1917 fell to the British forces. Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander-in-chief, chose the

Ypres salient as the site for his new offensive. He believed this area offered the greatest scope for a breakthrough, and the Royal Navy supported him, hoping

that the army could capture the ports on the Belgian coast that the Germans were using as bases for their submarine offensive against Britain's seaborne

trade.

The offensive began on 31 July 1917, but made disappointingly small gains. The British artillery bombardment, which was needed to shatter the enemy's defensive trench system, also wrecked the low-lying region's drainage system, and unusually rainy weather turned the ground into a wasteland of mud and water-filled craters. For three months, British troops suffered heavy casualties for limited gains.

The offensive began on 31 July 1917, but made disappointingly small gains. The British artillery bombardment, which was needed to shatter the enemy's defensive trench system, also wrecked the low-lying region's drainage system, and unusually rainy weather turned the ground into a wasteland of mud and water-filled craters. For three months, British troops suffered heavy casualties for limited gains.

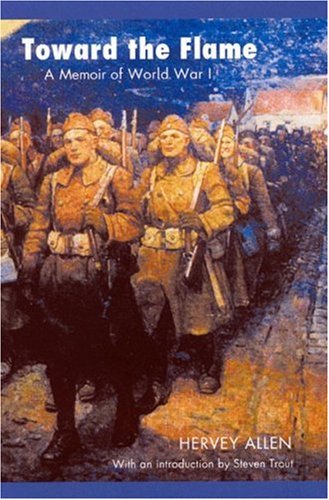

[Hooge] Chateau Wood: October 1917 and Today

Click on Image to Expand

On 16 August the attack was resumed, to little effect. Stalemate reigned for another month until an improvement in the weather prompted another attack on

20 September. The Battle of Menin Road Ridge, along with the Battle of Polygon Wood fought by the Australians on 26 September and the Battle of

Broodseinde on 4 October, established British possession of the ridge east of Ypres.

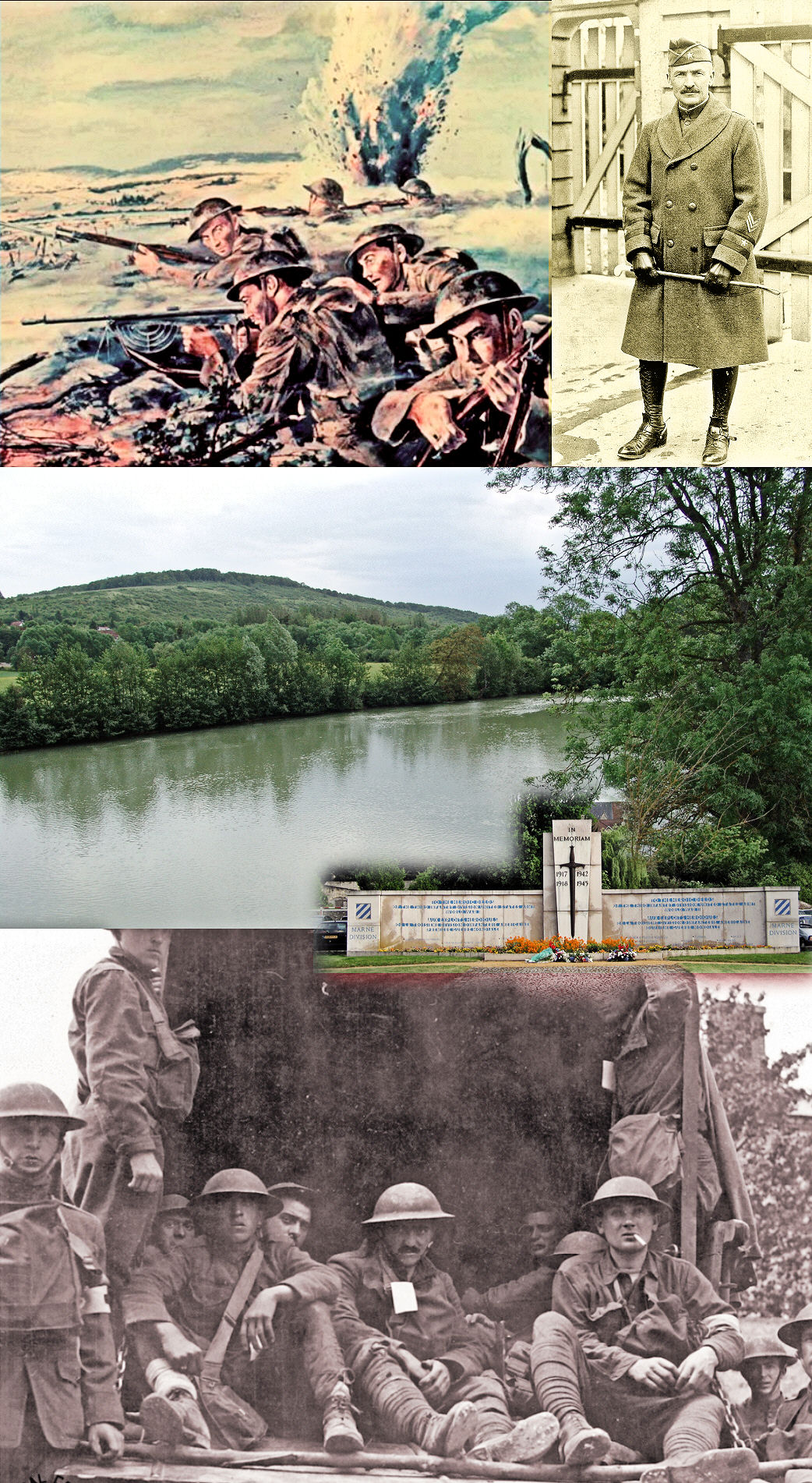

In October, the Canadian Corps, now commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Currie, took its place in the front lines. On 26 October the 3rd and 4th Divisions launched the first Canadian assault, in rain that made the mud worse than ever. Three days of fighting resulted in over 2,500 casualties, for a gain of only a thousand or so yards (1 km). A second attack went in on 30 October. In a single day, there were another 2,300 casualties — and only another thousand yards (1 km) gained. On 6 November, the 1st and 2nd Divisions launched a third attack that captured the village of Passchendaele, despite some troops having to advance through waist-deep water. A final assault on 10 November secured the rest of the high ground overlooking Ypres and held it despite heavy German shelling. This marked the end of the Passchendaele offensive.

In October, the Canadian Corps, now commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Currie, took its place in the front lines. On 26 October the 3rd and 4th Divisions launched the first Canadian assault, in rain that made the mud worse than ever. Three days of fighting resulted in over 2,500 casualties, for a gain of only a thousand or so yards (1 km). A second attack went in on 30 October. In a single day, there were another 2,300 casualties — and only another thousand yards (1 km) gained. On 6 November, the 1st and 2nd Divisions launched a third attack that captured the village of Passchendaele, despite some troops having to advance through waist-deep water. A final assault on 10 November secured the rest of the high ground overlooking Ypres and held it despite heavy German shelling. This marked the end of the Passchendaele offensive.

Passchendaele Village after the Battle and Today

Click on Image to Expand

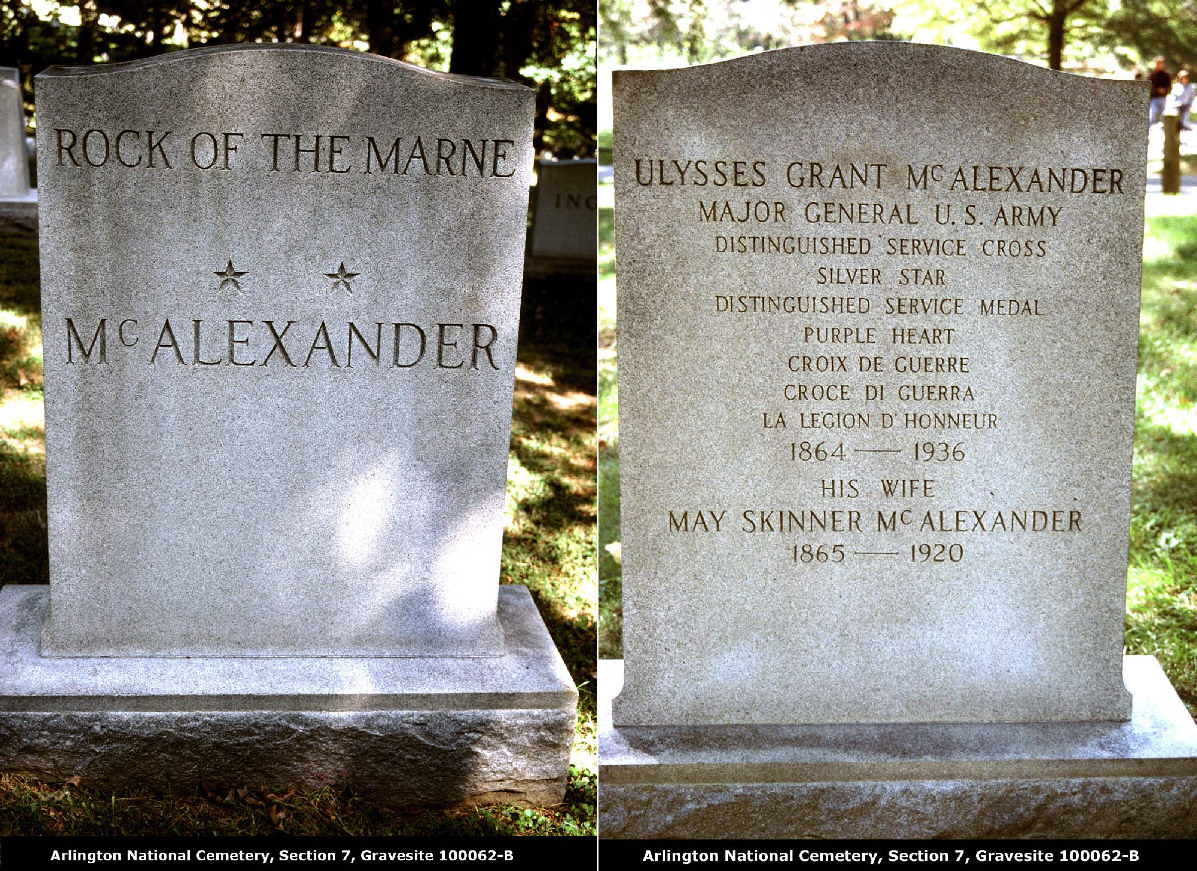

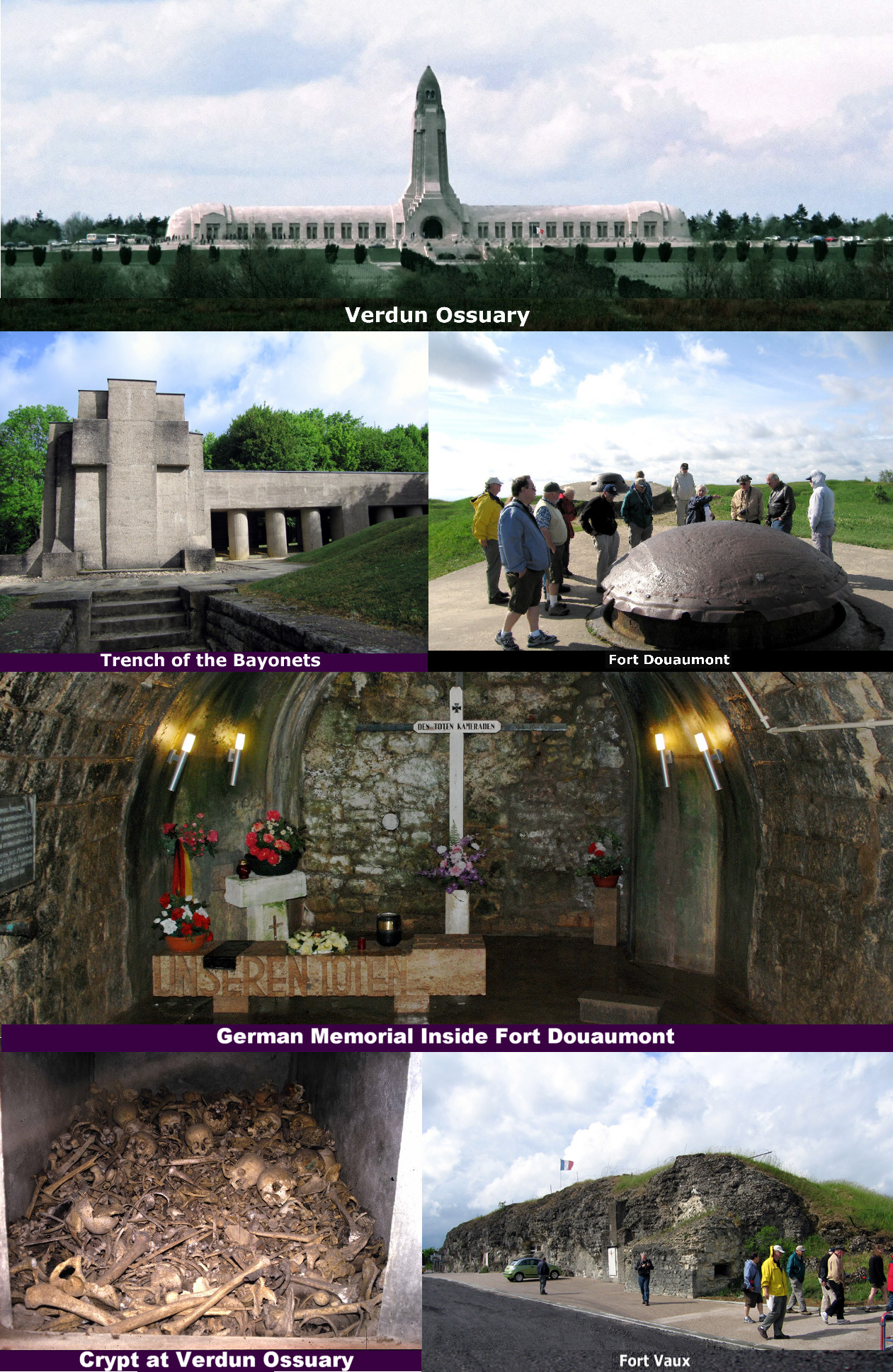

Passchendaele was one of the war's most futile battles. The unspeakable conditions led to terrible losses — nearly 260,000 British casualties, including over

15,000 Canadians killed and wounded. This suffering had produced no significant gains (though it did help wear down the German army). Passchendaele

has come, perhaps more than any other battle, to symbolize the horrors of the First World War.

Sources: Imperial War Museum, Library and Archives of Canada and BBC Website

Sources: Imperial War Museum, Library and Archives of Canada and BBC Website