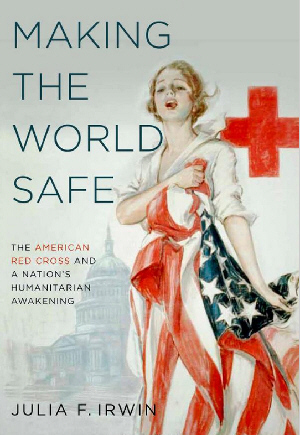

Making the World Safe:

The American Red Cross and a Nation's Humanitarian Awakening

By Julia F. IrwinPublished by Oxford University Press, 2013

Popular contemporary images of the American Red Cross depict it as a gigantic relief agency that swoops in during times of catastrophe to provide cups of hot coffee, bags of plasma, and plastic ponchos. We associate it with natural disasters, house fires, and life saving classes. But as this new, scholarly account deftly shows, the ARC is firmly rooted in a tradition of global humanitarianism.

Founded by Clara Barton in 1881 as a chapter of the International Red Cross, the American organization expanded its scope to include the humanitarian needs of all citizens, not just wounded soldiers. By broadly defining its mission, Barton hoped to win over the support of the general public to a program of relief at home and abroad and in peacetime as well as during war. According to Irwin, a history professor at the University of South Florida, success of the organization "would require further transformations in American understandings of the world and the part U.S. citizens and their government should play in it."

|

For historians of the Progressive Era and World War I, this study goes far in explaining the growing American involvement in overseas crises, the shift from voluntarism to professionalism in social reform, and the philosophical belief in the power of human intervention. The American Red Cross (ARC) first ventured into foreign civilian relief during the Spanish American War when workers, including Clara Barton, arrived in Cuba to distribute supplies. Although the U.S. military resisted their aid, calling ARC nurses "encumbrances", the McKinley administration publicly declared the ARC the agency that would carry out the government's international humanitarian aid. The U.S. Congress officially supported this position in 1900 by granting it a charter as the official relief organization of the country and requiring the organization to submit annual financial reports thereby creating a unique private-governmental partnership.

By the time of the U.S. entry into the Great War, the ARC had cemented its relationship with the U.S. government and had secured lucrative private sources of funding establishing an endowment of over $1 million. However, the board understood that its mission had to be embraced by American society for it to be a truly "national" organization. U.S. mobilization and entry into the war took care of that. By the Armistice in 1918, approximately one-third of the country's population (33 million Americans) were dues-paying members of the Red Cross. The U.S. public raised over $400 million for the organization and increased its endowment by 150 percent.

The mission of the American Red Cross during World War I was four-pronged-to provide care to wounded soldiers, assistance to American and Allied troops, aid to prisoners of war (as a member of the Geneva Convention), and help European civilians displaced by war. According to the author, "To an extent never before matched in U.S. history, Americans in the Great War years voluntarily elected to give their time and money to ameliorate the suffering of unknown children, women, and men in distant lands." Through the effective use of propaganda, both the ARC and the government equated support of civilian relief with patriotic duty. If a citizen supported the war effort, they were encouraged to donate their time and money to the ARC. In turn, if one supported humanitarian relief abroad, he or she was promoting an important arm of American diplomacy in Europe.

The ARC had its critics. Other organizations such as the Salvation Army, the YMCA, and the American Fund for the French Wounded were engaged in similar activities, but they did not enjoy the same level of government endorsement. This book spends little time looking at the complex web of humanitarian relief during and after the war because that is not its focus or scope. This study is not a history of the American Red Cross or a history of social service during the period but rather an examination of the hearts and minds of the American people while they grappled with the new world order. It makes a well-documented and convincing case. A fine piece of scholarship, Making the World Safe should be read by all those interested in the relationship of the state and society during the early twentieth century.

Margaret Spratt

By the time of the U.S. entry into the Great War, the ARC had cemented its relationship with the U.S. government and had secured lucrative private sources of funding establishing an endowment of over $1 million. However, the board understood that its mission had to be embraced by American society for it to be a truly "national" organization. U.S. mobilization and entry into the war took care of that. By the Armistice in 1918, approximately one-third of the country's population (33 million Americans) were dues-paying members of the Red Cross. The U.S. public raised over $400 million for the organization and increased its endowment by 150 percent.

The mission of the American Red Cross during World War I was four-pronged-to provide care to wounded soldiers, assistance to American and Allied troops, aid to prisoners of war (as a member of the Geneva Convention), and help European civilians displaced by war. According to the author, "To an extent never before matched in U.S. history, Americans in the Great War years voluntarily elected to give their time and money to ameliorate the suffering of unknown children, women, and men in distant lands." Through the effective use of propaganda, both the ARC and the government equated support of civilian relief with patriotic duty. If a citizen supported the war effort, they were encouraged to donate their time and money to the ARC. In turn, if one supported humanitarian relief abroad, he or she was promoting an important arm of American diplomacy in Europe.

The ARC had its critics. Other organizations such as the Salvation Army, the YMCA, and the American Fund for the French Wounded were engaged in similar activities, but they did not enjoy the same level of government endorsement. This book spends little time looking at the complex web of humanitarian relief during and after the war because that is not its focus or scope. This study is not a history of the American Red Cross or a history of social service during the period but rather an examination of the hearts and minds of the American people while they grappled with the new world order. It makes a well-documented and convincing case. A fine piece of scholarship, Making the World Safe should be read by all those interested in the relationship of the state and society during the early twentieth century.

Margaret Spratt

No comments:

Post a Comment