Quick Facts About the Meuse-Argonne Offensive:

Where: Northwest and north of Verdun

When: 26 September 1918 – 11 November 1918

Allied Units Participating: U.S. First Army commanded by General John J. Pershing until 16 October; then by Lt. General Hunter Liggett. Three U.S. corps plus one French corps; 23 American divisions rotating were involved.

German Forces: Approximately 40 German divisions from the Army Groups of the Crown Prince and MH General Max Carl von Gallwitz participated in the battle, with the largest contribution by the Fifth Army of Group Gallwitz commanded by General Georg von der Marwitz.

Memorable for:

Largest battle in American history by casualties and ground forces involved.

Learning ground for American military for the rest of the 20th century. Numerous future Army Chiefs of Staff and Marine Corps Commandants participated in the battle.

Gave America its largest overseas cemetery.

Source of many legends and traditions, including the Lost Battalion, Sgt. York, Balloon Buster Frank Luke.

When: 26 September 1918 – 11 November 1918

Allied Units Participating: U.S. First Army commanded by General John J. Pershing until 16 October; then by Lt. General Hunter Liggett. Three U.S. corps plus one French corps; 23 American divisions rotating were involved.

German Forces: Approximately 40 German divisions from the Army Groups of the Crown Prince and MH General Max Carl von Gallwitz participated in the battle, with the largest contribution by the Fifth Army of Group Gallwitz commanded by General Georg von der Marwitz.

Memorable for:

Click on Image to Expand

Left: Area of the Offensive

Right: Opening Attack

Brief Operational Description:

The area between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest was chosen for the U.S. First Army’s greatest offensive of the war because it was the portion of the German front which the enemy could least afford to lose. The lateral communications between German forces east and west of the Meuse were in that area and they were heavily dependent upon two rail lines that converged in the vicinity of Sedan and lay within 35 miles of the battle line. The nature of the Meuse-Argonne terrain made it ideal for defense. To protect this vitally important area, the enemy had established almost continuous defensive positions for a depth of ten to twelve miles to the rear of the front lines. The movement of American troops and materiel into position the night of 25–26 September 1918 for the Meuse-Argonne attack was made entirely under the cover of darkness. On most of the front, French soldiers remained in the outpost positions until the very last moment in order to keep the enemy from learning of the large American concentration. Altogether, about 220,000 Allied soldiers were withdrawn from the area and 600,000 American soldiers brought into position without the knowledge of the enemy.

Following a three-hour bombardment with 2,700 field pieces, the U.S. First Army jumped off at 0530 hours on 26 September. On the left, I Corps penetrated the Argonne Forest and advanced along the valley of the Aire River. In the center, V Corps advanced to the west of Montfaucon but was held up temporarily in front of the hill. On the right, III Corps drove forward to the east of Montfaucon and a mile beyond. About noon the following day, Montfaucon was captured as the advance continued. Although complete surprise had been achieved, the enemy soon was stubbornly contesting every foot of terrain. Profiting from the temporary holdup in front of Montfaucon, the Germans poured reinforcements into the area. By 30 September, the U.S. First Army had driven the enemy back as far as six miles in some places, but the advance was bogged down due to inexperienced units and commanders, poor logistics due to lack of transport, and non-existent roads and a lack of coordination between artillery and infantry.

The First Army had to learn while continuing the attack. General Pershing brought in experienced divisions and more combat engineers, and eventually appointed his best senior general, Hunter Liggett, to command First Army. George Marshall was giving the job of operations officer and new corps commanders were brought in. A new approach was prepared and a renewed general offensive was prepared.

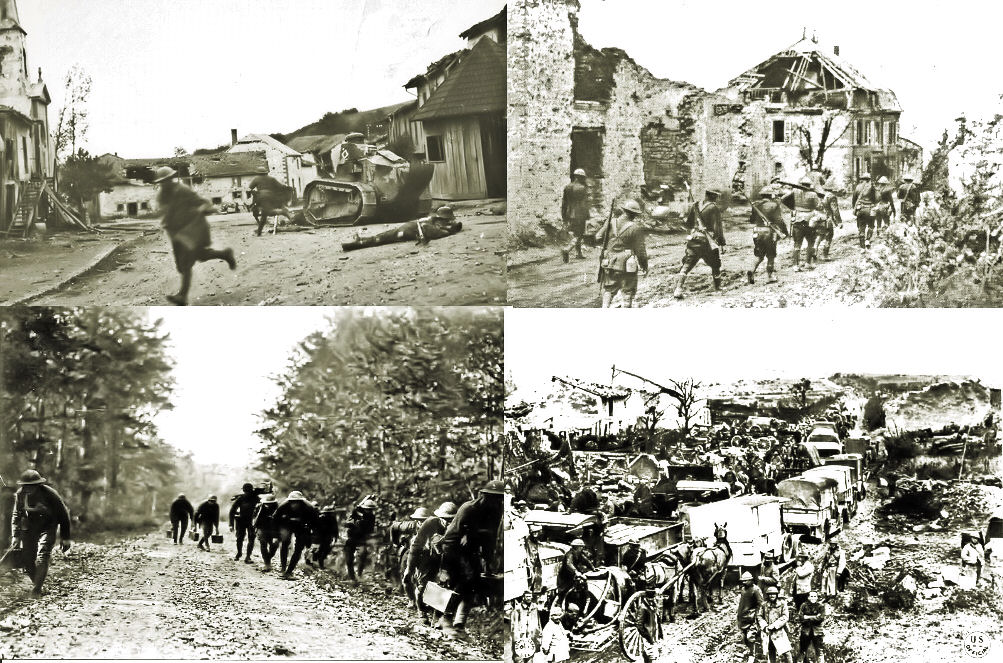

Click on Image to Expand

U.S. Troops in the Early Stages: Under Fire and Advancing in Villages; Advancing Down a Forest Road; Traffic Jam in Esnes

End Game of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

The final chapter of the great offensive by the U.S. First Army began at daybreak on 1 November after a two-hour concentrated artillery preparation. It would be the most important and successful American operation of the Great War.

The key roles in the assault were played by the III and V U.S. Corps, commanded by two future Army Chiefs-of-Staff, John Hines and Charles Summerall, respectively. They were supported by more artillery than ever assembled by the United States military. Tactics emphasized mobility and supply techniques were improved to support a rapid advance. The lessons of the earlier battles had been absorbed and corrections made. Its progress exceeded all expectations.

The final chapter of the great offensive by the U.S. First Army began at daybreak on 1 November after a two-hour concentrated artillery preparation. It would be the most important and successful American operation of the Great War.

The key roles in the assault were played by the III and V U.S. Corps, commanded by two future Army Chiefs-of-Staff, John Hines and Charles Summerall, respectively. They were supported by more artillery than ever assembled by the United States military. Tactics emphasized mobility and supply techniques were improved to support a rapid advance. The lessons of the earlier battles had been absorbed and corrections made. Its progress exceeded all expectations.

Click on Image to Expand

Last Phase of the Offensive as Executed

Note: Units on Right Shifting Axis Eastward

By early afternoon of 1 November, the formidable last Hindenburg Line position on Barricourt Heights had been captured, ensuring success of the whole operation. That night the enemy issued orders to withdraw west of the Meuse and the battle turned into a rout, sometimes with U.S. forces racing north faster than the retreating Germans. By 4 November, after an additional crossing of the Meuse by the U.S. First Army, the enemy was in full retreat on both sides of the river. Three days later, when the heights overlooking the city of Sedan were taken, the U.S. First Army gained domination over the German railroad communications there, ensuring early termination of the war.

Attention was shifting to the next U.S. strategic objective, Metz to the northeast, as the entire First Army began shifting their axis of attack in that direction. Meanwhile, the Second U.S. Army was renewing action down on the temporarily quiet St. Mihiel Sector. The Armistice ensued, however, before further major offensives could be mounted.

Firsthand Account – Thursday 26 September 1918:

That evening, about dusk I saw an unforgettable sight...I am lying down in the field...In front of me to my left I see the Hill and the battered town and fortress of Montfaucon. An attack is in progress. Soldiers are advancing up the hill with rifles and fixed bayonets in hand. They are filtering through the ruins, slowly but steadily. Shells are falling and crashing among them. Smoke and flying debris dot the hill. It is a gripping scene, a dramatic war picture, and here I am actually seeing it.

Sgt. Maximilian Boll, 79th Division

Firsthand Account – Tuesday 15 October 1918:

On October 15th, 1918, we were charging machine guns and men were being cut down like grass all around me. Then I was hit and fell, and couldn't get up. I laid there on the battlefield for three days and was assumed dead. Some man came by and said: Fields, what the hell are you doing laying there? The man picked me up, put me on his shoulder, and carried me three miles to the aid station.

Gangrene had already set-up, and they amputated my leg just below the knee. I was passing in and out of consciousness during the whole time and never recognized the man that carried me to safety. How he recognized me I'll never know because I was unshaven and was a mess. I've always regretted never knowing the man that saved my life.

Pvt. Clifton R. Fields, 32nd Division

Gangrene had already set-up, and they amputated my leg just below the knee. I was passing in and out of consciousness during the whole time and never recognized the man that carried me to safety. How he recognized me I'll never know because I was unshaven and was a mess. I've always regretted never knowing the man that saved my life.

Pvt. Clifton R. Fields, 32nd Division

Firsthand Account – Monday 11 November 1918:

While we were getting ready to take our wounded man to the rear, a runner appeared with the official news that an Armistice had been signed. Most everybody let out a few healthy yells, but I did not. For one reason, didn't feel much like yelling. I had some difficulty getting three more fellows to help me carry the stretcher.

Pvt. Clarence Richmond, 5th Marines, 2nd Division

Pvt. Clarence Richmond, 5th Marines, 2nd Division

Click on Image to Expand

American Column Advancing During Last Phase; German Prisoners; 11 November Celebration.

Sources: ABMC, Doughboy Center Website

Excellent recap. The theme for the high school academic decathlon is WWI, this blog is a wonderful introduction for the students to the Great War. This brief recap of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive is excellent. This battle was so important that after the war Hindenburg said the British food blockade and the American blow in the Argonne decided the war for the allies.

ReplyDeleteYou might want to consider adding a couple of outstanding memoirs to your students' reading list:

Delete(1) What I consider to be the best memoir written by a combatant, Pvt. Elton E. Mackin's "Suddenly We Didn't Want to Die: Memoirs of a World War I Marine," with an introduction by George B. Clark and a foreword by Lt. Gen. Victor B. Krulak, USMC (Ret.) (Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1993).

Mackin was a runner in the 5th Marines who first saw action as a replacement rifleman at Belleau Wood and was in the line to the bitter end, including the night river crossing of the Meuse on 10-11 Nov. 1918. He was awarded both the Navy Cross and the Army Distinguished Service Cross as well as two Silver Star citations.

(2) Almost equally compelling, in my opinion, is Lt. Hervey Allen's "Toward the Flame: A Memoir of World War I," with an introduction by Steven Trout (Lincoln: Univ. of Neb. Press, 2003).

Allen's narrative covers his 28th Division unit's march from the French coast beginning about 1 July 1918 and participation in the Second Battle of the Marne in the summer of 1918. It ends abruptly with the near annihilation of his company in the disastrous battle at Fismette on the Vesle River on 14 August.