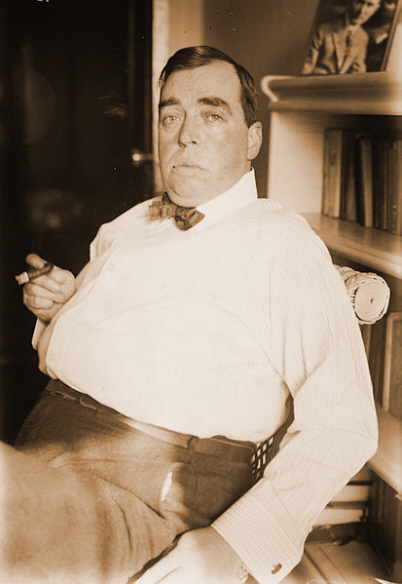

By Irvin S. Cobb, War Correspondent

American war correspondent Irvin Cobb covered World War I for the Saturday Evening Post, and wrote a book in 1915 about his experiences called Paths of Glory, from which this is excerpted. The villages described, which Cobb visited in the fall of 1914, are about 10 miles east of Liège. They found themselves in the path of the German First Army the first week of the war.

Irvin Cobb, War Correspondent

No; we were not in the town of Battice. We were where the town of Battice had been, where it stood six weeks ago. It was famous then for its fat, rich cheeses and its green damson plums. Now, and no doubt for years to come, it will be chiefly notable as having been the town where, it is said, Belgian civilians first fired on the German troops from roofs and windows, and where the Germans first inaugurated their ruthless system of reprisal on houses and people alike.

Literally this town no longer existed. It was a scrap-heap, if you like, but not a town. Here had been a great trampling out of the grapes of wrath, and most sorrowful was the vintage that remained.

Click on Image to Expand

Battice from a Distance and Down the Main Street

It was a hard thing to level these Belgian houses absolutely, for they were mainly built of stone or of thick brick coated over with a hard cement. So, generally, the walls stood, even in Battice; but always the roofs were gone, and the window openings were smudged cavities, through which you looked and saw square patches of the sky if your eyes inclined upward, or else blackened masses of ruination if you gazed straight in at the interiors. Once in a while one had been thrown flat. Probably big guns operated here. In such a case there was an avalanche of broken masonry cascading out into the roadway.

Midway of the mile-long avenue of utter waste which we now traversed we came on a sort of small square. Here was the yellow village church. It lacked a spire and a cross, and the front door was gone, so we could see the wrecked altar and the splintered pews within. Flanking the church there had been a communal hall, which was now shapeless, irredeemable wreckage. A public well had stood in the open space between church and hall, with a design of stone pillars about it. The open mouth of the well we could see was choked with foul debris; but a shell had struck squarely among the pillars and they fell inward like wigwam poles, forming a crazy apex. I remember distinctly two other things: a picture of an elderly man with whiskers one of those smudged atrocities that are called in the States crayon portraits hanging undamaged on the naked wall of what had been an upper bedroom; and a wayside shrine of the sort so common in the Catholic countries of Europe. A shell had hit it a glancing blow, so that the little china figure of the Blessed Virgin lay in bits behind the small barred opening of the shrine.

Of living creatures there was none. Heretofore, in all the blasted towns I had visited, there was some human life stirring. One could count on seeing one of the old women who are so numerous in these Belgian hamlets more numerous, I think, than anywhere else on earth. In my mind I had learned to associate such a sight with at least one old woman an incredibly old woman, with a back bent like a measuring worm's, and a cap on her scanty hair, and a face crosshatched with a million wrinkles who would be pottering about at the back of some half-ruined house or maybe squatting in a desolated doorway staring at us with her rheumy, puckered eyes. Or else there would be a hunchback crooked spines being almost as common in parts of Belgium as goiters are in parts of Switzerland. But Battice had become an empty tomb, and was as lonely and as silent as a tomb. Its people, those who survived, had fled from it as from an abomination.

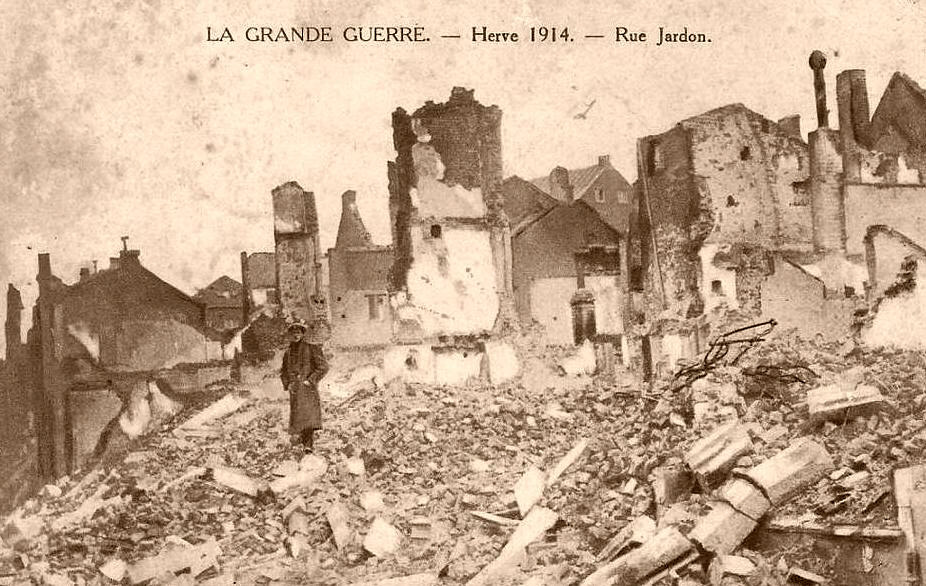

Beyond Battice stood another village, called Herve; and Herve was Battice all over again, with variations. At this place, during the first few hours of actual hostilities between the little country and the big one, the Belgians had tried to stem the inpouring German flood, as was proved by wrecks of barricades in the high street. One barricade had been built of wagon bodies and the big iron hods of road-scrapers; the wrecks of these were still piled at the road's edge. Yet there remained tangible proof of the German claim that they did not harry and burn indiscriminately, except in cases where the attack on them was by general concert.

Here and there, on the principal street, in a row of ruins, stood a single house that was intact and undamaged. It was plain enough to be seen that pains had been taken to spare it from the common fate of its neighbors. Also, I glimpsed one short side street that had come out of the fiery visitation whole and unscathed, proving, if it proved anything, that even in their red heat the Germans had picked and chosen the fruit for the wine press of their vengeance.

After Herve we encountered no more destruction by wholesale, but only destruction by piecemeal, until, nearing Liege, we passed what remained of the most northerly of the ring of fortresses that formed the city's defenses. The conquerors had dismantled it and thrown down the guns, so that of the fort proper there was nothing except a low earthen wall, almost like a natural ridge in the earth.

Click on Image to Expand

Herve

All about it was an entanglement of barbed wire; the strands were woven and interwoven, tangled and twined together, until they suggested nothing so much as a great patch of blackberry briers after the leaves have dropped from the vines in the fall of the year. To take the works the Germans had to cut through these trochas. It seemed impossible to believe human beings could penetrate them, especially when one was told that the Belgians charged some of the wires with high electricity, so that those of the advancing party who touched them were frightfully burned and fell, with their garments blazing, into the jagged wire brambles, and were held there until they died.

Before the charge and the final hand-to-hand fight, however, there was shelling. There was much shelling. Shells from the German guns that fell short or overshot the mark descended in the fields, and for a mile round these fields were plowed as though hundreds of plowshares had sheared the sod this way and that, until hardly a blade of grass was left to grow in its ordained place. Where shells had burst after they struck were holes in the earth five or six feet across and five or six feet deep. Shells from the German guns and from the Belgian guns had made a most hideous hash of a cluster of small cottages flanking a small smelting plant which stood directly in the line of fire. Some of these houses workmen's homes, I suppose they had been were of frame, sheathed over with squares of tin put on in a diamond pattern; and you could see places where a shell, striking such a wall a glancing blow, had scaled it as a fish is scaled with a knife, leaving the bare wooden ribs showing below. The next house, and the next, had been hit squarely and plumply amidships, and they were gutted as fishes are gutted. One house in twenty, perhaps, would be quite whole, except for broken windows and fissures in the roof as though the whizzing shells had spared it deliberately.

No comments:

Post a Comment