Friday, June 30, 2017

Thursday, June 29, 2017

Key Locations at Belleau Wood

This month marks the 99th anniversary of the U.S. Marine assault on Belleau Wood, so I thought I could share a few things that will help you understand what the media has to say about it. These comments and the graphic I've constructed below are based my own observations and questions and observations I've had from tour members on over a dozen visits to Belleau Wood.

1. It is bigger than most people expect; the map below covers over a square mile. You can't see it all from one position.

2. The attack direction (red arrows) is not north to south, but from the southwest to northeast. This is because the Marines were attacking the side of a salient created by the recent German push to Château-Thierry and the Marne river, which are southeast of Belleau Wood.

3. The American Cemetery is not shown on the graphic. It is just to the right of of the last letter of the "Hunting Lodge" caption, but the wood is on a plateau and there is an abrupt drop-off down to the cemetery.

4. The bottom illustration, C, by noted French artist George Scott, accurately depicts the wood at the end of the fighting. Following the battle of Belleau Wood, Scott traveled to the battlefield and interviewed Marine veterans of the struggle

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

Belgium's Clandestine Press in the Great War

|

| German Occupying Troops on Parade in Antwerp |

When the Germans invaded Belgium in 1914, very few Belgian newspapers succeeded in bringing their printing presses to a place of safety. Most journalists chose not to submit to censorship and stopped their activities. Nevertheless, the press, i.e. the censored press, remained the principal information and communication channel in the occupied country. However, other sources of information soon became available for the public.

The Belgian population found it difficult to bear the isolation from the world imposed by the occupier and remained hungry for information on the evolution of the conflict. The censored press, and the many rumors that circulated, could not meet this need. Thus, the rare Allied newspapers smuggled into the occupied territory sold at high prices.

The first clandestine papers or “prohibited” papers that appeared in 1914 largely constituted a solution to this problem. In many cases they reproduced the articles of the allied press. La Soupe, which appeared in Brussels for the first time in September 1914 was probably the most conspicuous and prolific manifestation of this type of clandestine paper. Only a year later, it had succeeded in publishing more than 500 copies, mostly reproducing political declarations. The Revue hebdomadaire de la Presse française (or Revue de la Presse from 1917 onward) was another, more elaborate example. Founded in Leuven in February 1915, it offered its readers in three or four issues per month a selection of articles from the major titles of the French press, sometimes supplemented with articles by its own journalists.

|

| Satire of German Governor von Bissing |

In the first months of 1915, a second wave of clandestine papers arrived. No longer content to serve as an echo of the international press, they wanted to be the voice of the occupied country. La Libre Belgique was without doubt the most famous and probably the most representative newspapers of this second category. Its goal was to express and orient the state of mind of the occupied people by counterbalancing the demoralization of the population caused by the censored press. In spite of several waves of arrests, the catholic Brussels paper succeeded in publishing 171 issues between February 1915 and November 1918, of which certain had a circulation of more than 20,000 copies distributed in nearly all of Belgium.

The success of La Libre Belgique was, however, exceptional. Most of the 77 known clandestine papers that appeared during the Great War were published for only a short period and with a limited circulation. Titles such as L’Âme belge, La Revue de la Presse, De Vrije Stem, or De Vlaamsche Leeuw did succeed in circulating during most of the occupation period, even if their numbers were not as high throughout the country as the ones of La Libre Belgique. The development of the clandestine press occurred mainly during the first part of the occupation. The repression, the material difficulties, and the fatigue of the war contributed to the decline of the phenomenon from 1916 onward.

|

| De Vrije Stem Issue on Food Shortages |

The struggle against the pro-German press took a peculiar turn in the north of the country where the Flemish movement founded several clandestine papers. Droogstoppel and De Vrije Stem, De Vlaamsche Wachter, and also De Vlaamsche Leeuw aimed at constituting a counterbalance against the activist censored press, which they considered an insult to the Flemish case

.

The Dutch-language clandestine papers were less numerous then their French-language counterparts: 14 Dutch-language titles and two bilingual, against 51 French-language titles. The statute making French Belgium's official language goes some way in explaining this, but the geography of the occupation probably also played a role. The occupation regime was particularly draconian along their lines of communication back to Germany and this encompassed more territory in the Flemish part of the country than in the francophone part. In fact, the majority of the clandestine papers appeared in the territory of the Generalgouvernement Belgien, in particular in Brussels and in a lesser degree in Antwerp.

By Emmanuel Debruyne at Belgian War Press

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Ray Rimell's Zeppelin Series

Reviewed by Terrence Finnegan

Zeppelins at War! 1914–1915

Albatros Productions, Ltd., 2014

The Last Flight of the L31

Albatros Productions, Ltd., 2016

The Last Flight of the L32

Albatros Productions, Ltd., 2016

|

| Purchase Here |

Rimell and Albatros use modern graphics combined with ample research to give the reader comprehensive access to the history of the airship and assorted operational insight. A case in point is the story of zeppelin ZV (LZ20). One of two airships employed by the 8th Armee to provide aerial reconnaissance and aerial bombardment of Russian forces in the opening days of the war, ZV was shot down on 25 August during a daytime sortie. Rimell’s research on the captured aircrew reveals only one was able to make it back to Germany. The rest died in Siberia.

|

| Purchase Here |

The subsequent Windsock Datafile Specials The Last Flight of the L31 and The Last Flight of the L32 were published in 2016 to appeal to interest from the centenarian commemorations. The Last Flight of the L31 covers Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Mathy’s last sortie over England. An extensive biography of the German aviator is provided, giving the reader a very comprehensive understanding of the lesser known German Naval Airship Division and aviators. To make the monograph even more appealing, the other side of the story is given detailing the life of the Royal Flying Corp aviator, 2/Lt. Wulstan Joseph Tempest, flying a BE2c (4556) and shooting the airship down with incendiary bullets “pumping lead into her for all I was worth.” Likewise, The Last Flight of the L32, follows the same format as L31 with Oberleutnant zur See Werner Peterson and aircrew being shot down by 2/Lt. Frederick Sowrey, a member of the legendary Sowrey family flying for the Royal Air Force in the 20th century.

|

| Purchase Here |

Ray Rimell’s and Albatros Production’s work is a credit to reliving military history through innovative applications of graphics and art design. It is a nice complement to the body of work telling the important story of the zeppelin’s contribution to aviation

Monday, June 26, 2017

The Centennial at the Grass Roots: Restoring Los Angeles's Victory Memorial Grove, Part II—Restoration and Re-dedication

[Part I of this article was presented on 1 June 2017 on Roads to the Great War. LINK]

|

| The Author with Friend Melissa Angert at the Re-dedication Ceremony |

So with my last post I left off right before the cleaning and planting day at Victory Memorial Grove. I'll backtrack just a bit first. Our main team of Lester Probst of the Hollywood Post 43 of the American Legion, and Jan Gordon and Kimberly Ables Jindra of Los Angeles—Eschscholtzia Chapter of DAR (LAE-DAR), had to meet several times with the City of Los Angeles Recreation and Parks Department to obtain the necessary rights of entry permits in order to do work in the park. However, once we bent their ear—the department was extraordinarily helpful!

|

| The Author, Kimberly Jindra (Author's Mom), and Lester Probst Brief the Volunteers |

Probst coordinated the participation of Disney Salute, the veterans group within Walt Disney Studios. They brought in The Mission Continues, a veterans organization that does community projects such as park cleanups. The city council district office also offered to pitch in, but by that time the most the most urgent need for the project was the availability of a port-a-potty on site for the cleanup day. The councilman's staff quickly obliged, free of charge.

|

| Volunteers Planting a Garden Around the Monument |

On Saturday 3 June 2017, the various obstacles were brushed aside as volunteers from the aforementioned organizations came together and spent several warm, sunny hours participating in a community-based clean-up day. The Mission Continues and Disney Salute provided donations of supplies, trash bags, topsoil, plants, dedicated, hardworking military veteran volunteers and their families, plus water and pizza to hydrate and feed everyone. Oh, let's not forget the Saturday assistance of Recs and Park. Three crew members worked right along with us, providing tools and trash disposal!

|

| Employees from Rosa Lowinger and Associates in the Midst of the Restoration |

This did wonders for the park’s general state. Volunteers picked up dozens of bags of unsightly trash and organic litter. They swept walkways and pathways clear of debris, loose soil, and rocks. They fought soil erosion with plantings and rock stabilization. They applied fresh soil and mulch and planted hundreds of native and/or regionally compatible, drought-resistant flowering plants to attract butterflies and other pollinating insects to the grove and beautify the appearance of this honored place.

Then, from Tuesday 6 June 2017 through Friday 9 June 2017, professional conservationists from Rosa Lowinger & Associates completed the painstaking monument restoration plan. They removed over 40 layers of paint and graffiti from the monument, treated the bronze, and successfully restored it to its original, beautiful appearance.

|

| Los Angeles Police Department Honor Guard at the Start of the Ceremony |

On Flag Day, Wednesday 14 June 2017, exactly 96 years to the day from the original setting of the monument by the Southern California Daughters of the American Revolution and with the monument hidden under a handmade replica of the same service flag that concealed it before, we were FINALLY ready.

|

| Kimberly and Courtland Jindra Welcome the Crowd |

A heartfelt re-dedication ceremony was presented by the Los Angeles Eschscholtzia Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The event brought together the Los Angeles Police Department Honor Guard, music sung by the Santa Monica barbershop chorus group, The Oceanaires, period poetry, a Doughboy re-enactor from the Great War Historical Society, a bugler, and a wreath laying.

We had a nice crowd including neighborhood folks, community groups, Legionnaires, DAR, members including CA State Regent Beverly Moncrieff, R&P employees, and even the Honorable Henri Vantieghem, Consul General of Belgium. Segments from the original 1921 and dedication ceremony, as well as a “roll call” of historical biographies of each of the individuals commemorated on the plaque, were presented by various veterans group members and friends. DAR members laid carnations atop the monument at the reading of each biography.

|

| Philip Dye–Member of the Great War Historical Society |

|

| The Author and the Man Who Made the Restoration Happen [Congratulations, Courtland—Well Done] |

It seems as if I have been working on this project forever, but I know by looking at other memorial projects around the country that this one actually moved fairly quickly. However, in a way this has just started. The monument may be restored, but the project will continue with more plantings and care taking. The conservation of the monument and beautification of the immediate area has already inspired the neighbors in the vicinity to commit themselves and their children to taking better care of this space. The restoration of the historic flag pole is a goal that the Daughters of the American Revolution and the American Legion are willing to take on next. We also hope to try and replant some trees to replace those that have died through the years. This park will hopefully continue to be a site of reverence and remembrance as well as leisure for years to come.

Sunday, June 25, 2017

Recommended: Doughboy Tragedy at Fismette, August 1918

|

| Fismette Across the Vesle River, Then and Now |

BY EDWARD G. LENGEL

Originally Published at Historynet.com

“Here they come!”

To the surviving Doughboys, the cry seemed like a death knell. Only a few dozen of them remained, scattered in the cellars of half-ruined houses and strung out behind a battered stone wall that spanned the northern edge of the village. They had been fighting for weeks and had not eaten a scrap of food for four days. Nerves frazzled and lungs wracked by gas, they slumped at their posts, seemingly more dead than alive. They had long since used up their grenades. German artillery had knocked out their only machine gun. Their rifle ammunition was running low. And they were trapped.

The Doughboys occupied the village of Fismette, on the north bank of France’s Vesle River. German troops occupied the steep hillsides that dominated the village to the north, east, and west. To the south the debris-choked river flowed 45 feet wide and 15 deep. A man could swim it if he didn’t mind slithering across submerged coils of barbed wire and risking German machine-gun fire. Otherwise, the only way across was a shattered stone footbridge that barely linked one bank to the other. Clambering over the bridge was a slow business—impossible in daylight, due to enemy mortars and machine guns, and risky at night.

For the past two hours the Germans had bombarded Fismette with every gun in their arsenal. Now dawn had broken, and German observers stationed on the hills above or flying in planes overhead would watch the Americans’ every movement for at least the next 12 hours. It was at this moment—when the Doughboys’ situation seemed impossibly desperate—the Germans chose to attack. A full battalion of elite stormtroopers armed with rifles, grenades, and flamethrowers rushed the weak American line. As thick black smoke and flames spurted toward them, the ranking American officer, Major Alan Donnelly, could find only two words to say.

“Hold on!” he shouted.

The Pennsylvania National Guard’s 28th Division, the famed “Keystone,” was among the best the Americans had in France in the summer of 1918. “They struck me as the best soldiers I had ever seen,” said Brig. Gen. Dennis Nolan, commander of the division’s 55th Infantry Brigade. “They were veterans, survivors who didn’t seem to be oppressed by the death of other men.”

|

| German Flamethrower Team Similar to Those Deployed at Fismette |

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the Pennsylvania National Guard’s 109th, 110th, 111th, and 112th infantry regiments formed the 7th Division. Later that year the unit was re-designated the 28th Division, assigned to the American Expeditionary Forces and shipped to France under the command of Maj. Gen. Charles H. Muir. Though grouchy and inflexible, Muir knew what fighting meant. Serving as a sharpshooter during the Spanish-American War, he had received the Distinguished Service Cross for singlehandedly killing the entire crew of a Spanish artillery piece. Muir’s men affectionately called him “Uncle Charley.”

The Pennsylvanians entered combat for the first time in early July 1918, fighting as part of the American III Corps under Maj. Gen. Robert Lee Bullard. As no independent American Army in France yet existed, however, they were under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Jean Degoutte’s French Sixth Army. Attacking northward from the Marne River about 50 miles east of Paris, they pushed into an enemy-held salient backed by the Aisne River. On 4 August the Americans captured the town of Fismes on the south bank of the Vesle River. They had advanced 20 miles in just over a month and cleared out most of the German salient. Degoutte nevertheless ordered the 28th Division to cross the Vesle, capture Fismette and hold it as a bridgehead.

Muir and Bullard vehemently disagreed with Degoutte’s orders. The bridgehead at Fismette was too vulnerable, they argued. Enemy-held hills overlooked it on all sides, and withdrawal under fire over the Vesle would be next to impossible. But Degoutte would have none of it, and the American generals had to swallow their objections. Until the independent American Army that General John J. Pershing had sought for so long became a reality, they had no choice but to follow the Frenchman’s orders.

The Germans did not concede Fismette easily. On the night of 6–7 August , troops of the 112th Infantry attacked the village, but German resistance was too strong, and they had to withdraw. They tried again the following morning after American artillery had laid down a heavy barrage, and after a savage street fight they gained enough of a toehold to hang on. For the next 24 hours attacks, counterattacks and constant hand-to-hand fighting engulfed Fismette in an inferno of flame, smoke and noise.

Lieutenant Hervey Allen, a literate young man from Pittsburgh who would later become a successful novelist, approached the riverbank opposite Fismette late on the evening of 9 August. His company of the 111th Infantry had been fighting the Germans for six weeks and had not received rations for the past few days. Allen’s thoughts were less than cheerful as he gazed across the Vesle at a churning cloud of smoke flickering with muzzle flashes and echoing with gunfire and explosions. Somewhere in there lay Fismette.

The infantrymen crossed the stone bridge just after midnight. As they picked their way forward, they prayed enemy flares would not light up the sky and expose them to machine-gun fire. Fortunately, the sky remained dark. Rifle fire intensified, however, as the Doughboys entered Fismette. The Germans still held much of the village and contested the Americans house to house. Allen’s captain led them through the village, dodging and sprinting, until they reached its northern edge just before dawn. Ahead, on a half-wooded upward slope cut by a small gully, German machine guns barked at them furiously from the shelter of some trees.

|

| Lt. Hervey Allen |

The captain ordered an attack but was shot dead as he led his men into the open. Allen and the others continued forward another 50 yards before retiring to the village with heavy losses. The few remaining officers in Allen’s company held a hurried conference in an old dugout. Their standing orders were to attack and seize the hills above Fismette, but this seemed insane when even survival was problematic. One of them, they decided, had to return to headquarters in Fismes and seek further orders. Allen said he could swim, so the other officers chose him.

Allen approached the riverbank by slithering down a muddy ditch, dragging his belly painfully over strands of barbed wire half-submerged in the mud. Small clouds of German mustard gas filled the ditch in places, and although he wore his mask, the gas burned his hands and other exposed patches of skin. Enemy shells fell nearby, stunning him into near-unconsciousness. Allen nevertheless made it to the river’s edge, where he slipped into the water, discarding his gas mask and pistol.

The lieutenant crossed the Vesle beneath the bridge, sometimes swimming and other times crawling over submerged barbed wire. As he reached the opposite bank, Allen’s heart sank. American and German machine guns constantly raked the shore. There seemed no way forward and no way back. “I lay there in the river for a minute and gave up,” he later remembered. “When you do that, something dies inside.”

After a moment, fortunately, Allen noticed a small culvert that offered just enough cover for him to make his way into Fismes. A few minutes later he was racing down rubble-strewn streets toward the dugout serving as battalion headquarters. No signposts were necessary—all he had to do was follow the macabre trail of dead runners’ corpses. He arrived at the dugout to the sight of an unexploded German shell wedged into the wall just over the entrance. Inside, Allen waded through a crowd of officers, wounded soldiers, and malingerers to reach his battalion major. The major looked rather pleased with himself, for he had so far received only positive reports of the fighting in Fismette. Allen, as the only eyewitness present, quickly disabused him of his optimism. His duty done, the lieutenant saluted, moved to a corner and lost consciousness.

Several hours later an officer shook Allen awake and ordered him to guide a group of reinforcements back into Fismette. Night had fallen. Little remained of the bridge, and the surrounding area was strewn with shell holes, broken equipment, and pieces of men. A sentry warned that the slightest sound would provoke German machine guns to open fire on the bridge, and that several runners had been killed trying to cross. Waves of nausea engulfed Allen. For a moment his resolve wavered. “No more machine guns, no more!” he said to himself over and over. An American sniper, sheltering nearby and waiting to fire at German muzzle-flashes, hissed, “Don’t stoop down, lieutenant—they are shooting low when they cut loose!”

Allen sucked in his stomach and led his men carefully over the bridge. As they reached mid-span, an enemy flare lit up the sky. The Doughboys stood frozen and prepared to die. “That,” Allen later recalled, “was undoubtedly the most intense moment I ever knew.” The flare seemed to float eternally, until it finally descended in a slow arc, sputtered and went out. Miraculously, the enemy had not fired a shot.

The hours that followed sank only partially into Allen’s memory, passing in a haze of sights, sounds and impressions. What he remembered most was weariness. “In that great time,” he later wrote, “there was never any rest or let-up until the body was killed or it sank exhausted.” Around him, the fighting continued without letup.

|

| Lt. Bob Hoffman |

Months afterward many members of the regiment would receive medals in tribute to their bravery in Fismette. Sergeant James I. Mestrovitch rescued his wounded company commander under fire on 10 August and carried him to safety. Mestrovitch would receive the Medal of Honor for this act of heroism—but posthumously, as he was killed in action on 4 November.

Lieutenant Bob Hoffman would return home with a Croix de Guerre. He spent his days and nights in Fismette scouting German positions and fighting off counterattacks. One morning Hoffman noticed German preparations for an attack and deployed his men in a block of ruined houses they had linked together with strongpoints and tunnels. The Americans had just taken their positions, poking their rifles through apertures in the crumbling stone walls, when German soldiers came rushing down the street. Hoffman never forgot the sight: “Clumpety-clump, they were going, with their high boots and huge coal-bucket helmets. I can see them coming yet—bent over, rifle in one hand, potato-masher grenade in the other; husky, red-faced young fellows, their eyes almost popping out of their heads as they dashed down the street, necks red and perspiring.”

Continue reading the entire article at:

Saturday, June 24, 2017

What Happened at Zivy Crater?

|

| Zivy Crater Cemetery Looking West (Away from Vimy Ridge) |

Zivy Crater–now the site of a Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery–sits right at the foot of Vimy Ridge and was on the jump-off line for the Canadian assault of 9 April 1917. I'd never visited it before, but I thought after looking at Google Earth that it would be the perfect spot to start the Vimy Ridge segment of my recent Western Front Battlefield Tour. Unfortunately, when we got there the view of Vimy Ridge was perfectly blocked by an overpass and surrounding trees. We did learn the story of its role in the war from the informational kiosk at the site. The cemetery is the final resting place for 53 fallen of the war, mostly Canadians, who died in the opening attack of 9 April.

After the War, Zivy Crater Was Something of a Pilgrimage Site for Canadian Visitors

Photos: Dudley Heer and CWGC

Friday, June 23, 2017

Thursday, June 22, 2017

A Roads Classic: How Did the Disaster at Caporetto Occur?

With the centennial of the Italian Front's most famous battle, I thought readers would like to see this article we presented in our first year. I'll be leading a tour of the Caporetto battlefield this summer, so if you would like some information about the trip, just email me at greatwar@earthlink.net

MH

How Did Caporetto Occur?

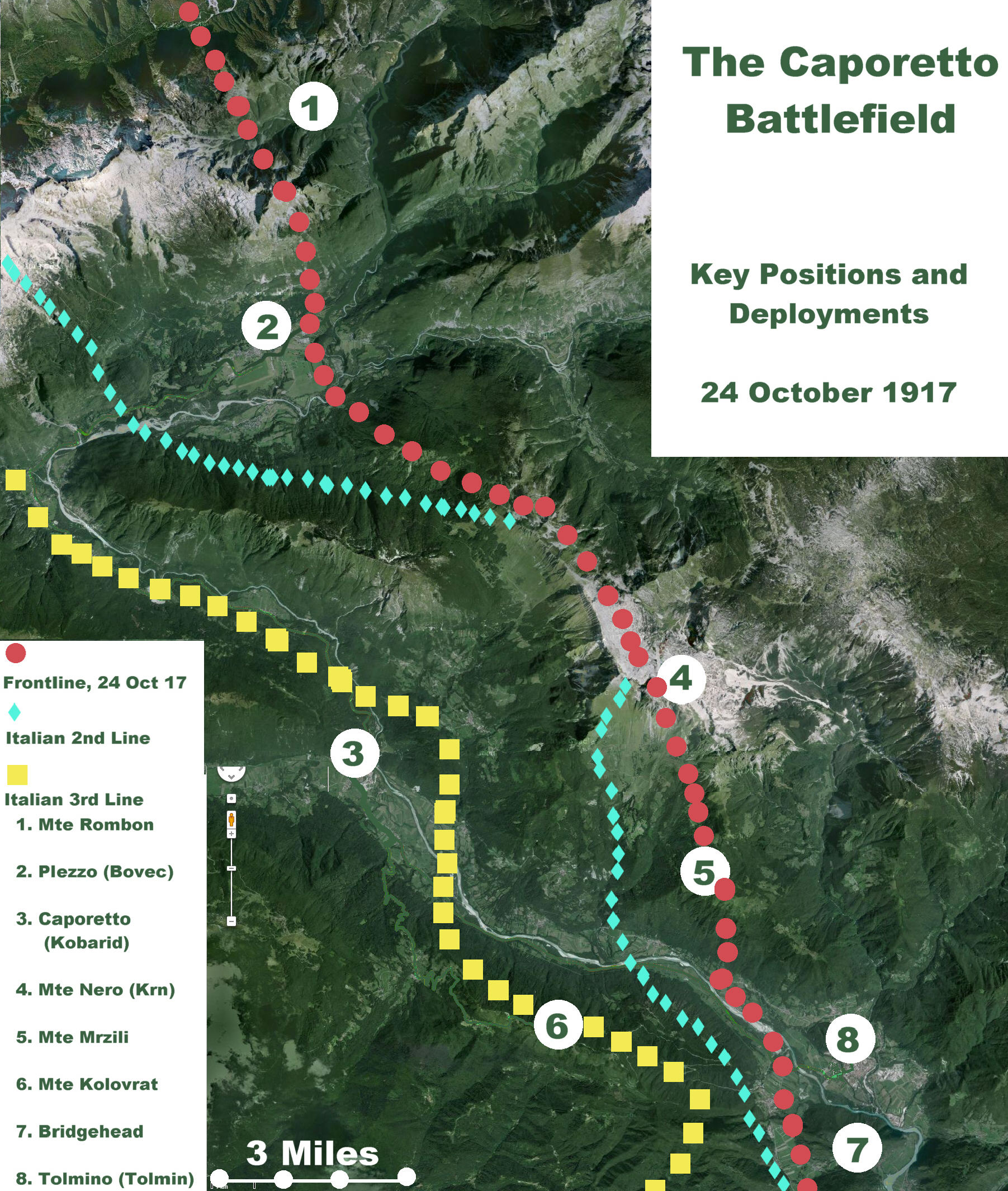

The Caporetto offensive launched 24 October 1917 along the Isonzo River, is considered one of the most decisive victories of the 20th century. It was boldly planned, very ably organized, and well executed. While two Austrian armies, under General Svetozar Borojevic von Bojna, attacked the Italian Third Army on the Carso and Bainsizza Plateaus on the lower ground near the Adriatic shore, further north in the more mountainous part of the Isonzo sector, the German-Austrian Fourteenth Army, targeted the Italian Second Army. Comprising the six German divisions and nine Austrian under German General Otto von Below, with Konrad Krafft von Dellmensingen as his chief of staff, the Fourteenth Army's masterful double breakthrough proved decisive, annihilating the Second Army.

The assault stunned Italians troops and their commanders, who fell back in confusion: Below's van reached Udine, the former site of the Italian general headquarters, by October 28 and was on the Tagliamento River by October 31. . .The Italians [eventually] sustained about 500,000 casualties, including 250,000 taken prisoner. How could such a catastrophe occur in so short a period? The answer–I believe–lies in the faulty deployment by the Italian Commando Supremo. Even the anxious Italian King, who visited Caporetto a few days before the attack, expressed skepticism over the dispositions made by his generals. The map and photos below should demonstrate these weaknesses to you.

Click on Image to Expand

Important things to note: A. The opening day's battlefield was huge, roughly 12 x 12 miles; B. The front line and the Italian defensive lines weave back and forth across the Isonzo (Soca) River; C. The large gap between Italian 2nd and 3rd lines; D. Tight fit of all three Italian Lines west of Tolmino (8).

Following the Map from Top (North) to Bottom (South)

- Mte. Rombon (1) was the site of ferocious mountaintop fighting right up to the opening of the 24 October offensive. It marks the northern extent of the Caporetto battlefield. Occupied by Bosnian troops, it gave the German-Austrian forces an excellent view of their enemy's deployments before the operation. Far below its peak on the river lies the village of Plezzo (2).

- Plezzo (2) was just behind the front line of 24 October. The front here crossed the Isonzo, meaning attacking forces would not need to force a river crossing, simplifying things greatly for them. Here Austrian divisions and German gas officers would execute the most successful gas attack of the First World War, and charge through a huge opening that opened the road to Caporetto. The photos below show the area today.

Click on Image to Expand

The view from the 3rd Italian line above the river bend looking northeast toward Plezzo (2) along the narrow river valley. Mte. Rombon (1) is in the far distance. In this area the mountains are quite close on either side of the river.

Click on Image to Expand

However, just along the river near Plezzo (2), there are some low flat spaces. Italian forces deployed here were hit with a lethal gas barrage, allowing a clean breakthrough by Austrian divisions. One of the dirty secrets of WWI is that gas attacks were effective when used intelligently.

- Moving south past a big bend in the Isonzo is the town of Caporetto (3), the opening objective and namesake of the battle. It is a road-hub at the head of a second valley (off to the right on the photo below) and its capture allowed the deep pursuit into northern Italy after the initial rout.

- Mte Nero (4), at 2244 meters on the left of the photo, was on the front line on 24 October. Three Italian divisions, the 43rd, 46th, and 50th, were deployed just below its peak and that of a second summit on Mte Mrzili (5). Heavy fog and rain on the morning of the battle obscured the vision of these units. South of Caporetto most of the Italian 2nd line and all of the 3rd line were on the opposite side of the river. By mid morning, unbeknownst to them, the three divisions on Nero and Mrzili were being flanked from their left (also left on the photo) by the enemy units that had broken through at Plezzo (2) and were marching down the river edge. This was not their only danger, though.

Click on Image to Expand

About 10 miles south of Caporetto (3) lies another river town, Tolmino (8). General von Below was executing a second breakthrough there.

- Below is a spectacular view of Tolmino (8) from a hang glider above the Isonzo. Once again the front line and 2nd and 3rd Italian lines cross the river at a perpendicular just north of the town. Here the Italian positions were too tightly bunched. Both the town and the high hill to the right of the town–part of the Tolmino Bridgehead (7)–were occupied by German troops, as was the hill to the left of town which offers a superb view down the valley towards Caporetto. Once again the Central Powers were able to attack on both sides of the river at the same time. Additionally, a strong attack here had the potential of punching through all three Italian positions very quickly; and an assault from the Bridgehead (7) could be mounted attacking downhill. It was a position of maximum danger for the Italian Army and maximum opportunity for their opponents.

Click on Image to Expand

For orientation purposes: Just out of view to the left of the glider is Mte Mrzili (5) and over the pilot's left shoulder is Mte Nero (4); ahead is Tolmino (8) in the center and the Bridgehead (7) is to the right; out of view on pilot's right is Mte. Kolovrat (6).

- The attack in this area had three branches. Out of Tolmino (8): One German division attacking out of Tolmino advanced along the river and headed for Caporetto (3). This group would join up later in the morning with the group advancing from the Plezzo (2) breakthrough. The three Italian divisions deployed along the slopes of Mrzili (5) and Nero (4) were cut-off and captured en masse. Many of those troops did not fire a shot in the battle. Caporetto (3), itself, was secured by 1600 hours.

- Also out of Tolmino (8), German Alpenkorps (including Lt. Erwin Rommel) crossed over advanced on the other side of the river up onto the Mte Kolovrat (6) range to reduce the strong points of the 2nd and 3rd Italian positions. Over several days each of these strong points were eliminated.

- The third group attacked out the Bridgehead (7) and targeted the right flank of the Second Army where its XXVII Corps was deployed. A relief of units was in progress when the attack hit and the confused Italian forces were devastated.

- In summary, almost all the troops in the three Second Army lines were killed or taken prisoner in the early stages of the fighting. Subsequently those troops in reserve and in the rear areas were threatened by a double flanking maneuver that quickly followed the initial double breakthroughs out of Plezzo and Tolmino. After capturing Caporetto, the northern Austro-German force pushed west, then south into the Veneto. Meanwhile, the force that advanced out of the Tolmino Bridgehead also threatened the flanks of the remains of Second Army on one side of its thrust and the Italian Third Army on the other side. This effectively collapsed the entire Italian position along the length of the Isonzo River, leading to the headlong retreat that is the hallmark and most remembered aspect of the Battle of Caporetto.

Click on Image to Expand

The view from an artillery position on the Italian 3rd line on Mte Kolovrat (6). The hill just below marked the 2nd line. Rommel captured a position there early in the battle. On the left just across the river, the early slopes of Mte. Mrzili (5) where the Italian 46th Division found itself stranded can be seen.

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

Under Bombardment

|

| View of a Bombardment |

We never become accustomed to the shellfire. Its terror for us increases with each passing day. The days out on rest ease our harried nerves, but as soon as we are back in the line again we are as fearful and jumpy as the newest recruit. With the first hiss and roar of a shell we become terror-stricken as of old.

We look at each other with anxious, frightened faces.

Our lips tighten.

Our eyes open wide.

We do not talk.

What is there to say?

Talk of the coming offensive continues.

The sector becomes more tumultuous.

The guns rage all night.

We "stand to" long before dawn and wait at the parapets expecting an attack until long after sunrise.

The fatigues are innumerable.

Every night there are wiring parties, sapping parties, carrying parties. We come back exhausted from these trips. We throw ourselves down in the dugouts for an hour's sleep.

But we do not rest.

There is no time for rest. We stagger around like drunken, forsaken men. Life has become an insane dream.

Sleep, sleep–if only we could sleep.

Our faces become grey. Each face is a different shade of grey. Some are chalk-coloured, some with a greenish tint, some yellow. But all of us are pallid with fear and fatigue.

It is three in the morning.

Our section is just back from a wiring party.

The guns are quiet.

Dawn is a short while off . . .

We sit on the damp floor of the dugout.

We have one candle between us and around this we sit chewing at the remains of the day's rations.

Suddenly the bombardment begins.

The shells begin to hammer the trench above.

The candlelight flickers.

We look at each other apprehensively. We try to talk as though the thing we dread most is not happening.

The sergeant stumbles down the steps and warns us to keep our battle equipment on.

The dugout is an old German one; it is braced by stout wooden beams. We look anxiously at the ceiling of the hole in which we sit.

The walls of the dugout tremble with each crashing explosion.

The air outside whistles with the rush of the oncoming shells.

The German gunners are "feeling" for our front line.

The crashing of the shells comes closer and closer. Our ears are attuned to the nuances of a bombardment. We have learned to identify each sound.

They are landing on the parapet and in the trench itself now.

We do not think of the poor sentry, a new arrival, whom we have left on lookout duty.

We crowd closer to the flickering candle.

Upstairs the trench rings with a gigantic crack as each shell lands. An insane god is pounding it with Cyclopean fists, madly, incessantly.

We sit like prehistoric men within the ring of flickering light which the candle casts. We look at each other silently.

A shell shatters itself to fragments near the entrance of the dugout.

The candle is snuffed out by the concussion.

We are in complete darkness.

Another shell noses its shrieking way into the trench near the entrance and explodes. The dugout is lit by a blinding red flash. Part of the earthen stairway caves in.

Shellfire!

In the blackness the rigging and thudding over our heads sounds more malignant, more terrible.

We do not speak.

Each of us feels an icy fear gripping at the heart.

With a shaking hand Cleary strikes a match to light the candle. The small flame begins to spread its yellow light. Grotesque, fluttering shadows creep up the trembling walls.

Another crash directly over our heads!

It is dark again.

Fry speaks querulously:

"Gee, you can't even keep the damned thing lit."

At last the flame sputters and flares up.

Broadbent's face is green.

The bombardment swells, howls, roars.

The force of the detonations causes the light of the candle to become a steady, rapid flicker. We look like men seen in an ancient, unsteady motion picture.

The fury of the bombardment makes me ill at the stomach.

Broadbent gets up and staggers into a corner of our underground room.

He retches.

Fry starts a conversation.

We each say a few words trying to keep the game alive. But we speak in broken sentences. We leave thoughts unfinished. We can think of only one thing–will the beams in the dug-out hold?

We lapse into fearful silences.

We clench our teeth.

It seems as though the fire cannot become more intense. But it becomes a little more rapid–then more rapid. The pounding increases in tempo like a noise in the head of one who is going under an anesthetic. Faster.

The explosions seem as though they are taking place in the dugout itself. The smoke of the explosives fills the room.

Fry breaks the tension.

"The lousy swine," he says. "Why don't they come on over, if they're coming?"

We all speak at once. We punctuate our talk with vile epithets belittling the sexual habits of the enemy. We seem to get relief in this fashion.

In that instant a shell hurtles near the opening over our heads and explodes with a snarling roar. Clods of earth and pieces of the wooden supports come slithering down the stairway.

It is dark again. In the darkness we hear Anderson speak in his singsong voice:

"How do you expect to live through this with all your swearing and taking the Lord's name in vain?"

For once we do not heap abuse and ribaldry on his head. We do not answer.

We sit in the darkness, afraid even to light the candle. It seems as though the enemy artillerymen have taken a dislike to our candle and are intent on blowing it out.

I look up the shattered stairway and see a few stars shining in the sky.

At least we are not buried alive!

The metallic roar continues.

Fry speaks: "If I ever live through this, I'll never swear again, so help me God."

We do not speak, but we feel that we will promise anything to be spared the horror of being buried alive under tons of earth and beams which shiver over our heads with each explosion. Bits of earth from the ceiling begin to fall . . .

Suddenly, as quickly as it began, the bombardment stops.

We start to clear up the debris from the bottom of the stairs.

To think we could propitiate a senseless god by abstaining from cursing!

What god is there as mighty as the fury of a bombardment? More terrible than lightning, more cruel, more calculating than an earthquake!

How will we ever be able to go back to peaceful ways again and hear pallid preachers whimper of their puny little gods who can only torment sinners with sulfur, we who have seen a hell that no god, however cruel, would fashion for his most deadly enemies?

Yes, all of us have prayed during the maniac frenzy of a bombardment.

Who can live through the terror-laden minutes of drum-fire and not feel his reason slipping, his manhood dissolving?

Selfish, fear-stricken prayers–prayers for safety, prayers for life, prayers for air, for salvation from the death of being buried alive . . .

Back home they are praying, too–praying for victory–and that means that we must lie here and rot and tremble forever . . .

We clear away the debris and go to the top of the broken stairs.

It is quiet and cool.

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

Kitchener's Mob

Reviewed by Jane Mattisson

Kitchener's Mob: The New Army to the Somme

by Peter Doyle and Chris Foster

The History Press, 2016

Kitchener's Mob tells the hectic story of the raising of Kitchener's Army in August and September 1914. The number of volunteers who joined Kitchener's Army was higher than the total number of soldiers obtained by conscription in 1916 and 1917 combined. In fact Kitchener and the War Office were able to add five New Armies to Britain's military forces. Kitchener's first call was for 100,000 men; this goal was reached within just two weeks. A further 100,000 men were required almost immediately. Feelings of patriotism ran high, as in the case of Harry Gilbert Tunstill, a land agent and county council representative who, on 24 August had just returned from a trip to Russia and immediately took on the responsibility of raising men to serve in the New Army. All but two of the New Army divisions saw action in France and Belgium. As Boyle and Foster demonstrate, the men of Kitchener's Army suffered greatly during the first few months of the war because of a severe shortage of weapons, equipment, and accommodation.

Kitchener's Mob is divided into five chapters: Men of the Moment, Kitchener's Men, Pals, Road to the Somme, and End of an Experiment. The first chapter describes Kitchener's qualities as a leader in time of war. Kitchener's Army quickly entered the popular imagination, as evidenced in the wide range of posters, postcards, and advertisements reproduced in Doyle and Foster's study.

Chapter two, "Kitchener's Men", describes the training of the volunteers, and the production of their uniforms and equipment. Among the many evocative illustrations in this chapter are the photographs of individuals and groups at camp and in training. Equipment was hard to come by and of questionable quality. All the same, the total weight carried by Kitchener's men was between 61 and 65 lbs., which included clothing, arms, ammunition, accoutrements, rations, and water.

Conditions in the camp were far from comfortable, as the postcard text below illustrates:

Down in our blinking camp,

We're always on the ramp,

That's where we cop the cramp,

Through sleeping in the damp. (p. 81)

It is clear, however, that despite the difficult conditions, spirits ran high.

"Pals", the third chapter of Kitchener's Mob, describes how the retreat from Mons in August 1914 spurred on the recruitment campaign as fears grew that the Expeditionary Force would be pushed back to the Channel ports. The Pals concept grew out of this fear along with a subsequent request that the City of London raise a whole battalion of stockbrokers. Two weeks later, a letter from Lord Derby appeared in the Liverpool Echo, addressed specifically to the commercial classes:

It has been suggested to me that there are many men, such as clerks and others engaged in commercial business, who wish to serve their country and would be willing to enlist in the battalion of Kitchener's New Army if they felt assured that they would be able to serve with their friends and not to be put in a battalion with unknown men as their companions. Lord Kitchener has sanctioned my endeavouring to raise a battalion that would be composed entirely of the classes mentioned, and in which a man could be certain that he would be amongst friends (p. 95).

Pals regiments, from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland became a vital part of Kitchener's Army. A particularly moving photograph reproduced in the chapter is that of Private 15/1545 Tom Scawbord, who was killed on the first day of the Somme on 1 July 1916 (p. 119). The chapter also describes recruitment in Ulster, showing a photograph of the Ulster Volunteers in 1912; they are a pathetic sight as they march with neither uniforms nor ammunition.

Chapter Four, "The Somme", is richly illustrated with photographs from the front, showing the trenches, dugouts, labor battalions, and German barbed wire. There are also extracts from letters such as the one below, which makes it clear that soldiers found it difficult to describe what it was really like at the front:

It is awfully cold and dismal at nights. I would refer you to Rudyard Kipling for a description of the dawn and the close of the day, when soldiers stand to arms, to give you a truer idea of something no-one but a good poet can describe (p. 174).

The chapter also contains a section on Gallipoli and Egypt.

It is, however, the section on the Somme that is the most powerful. With the aid of maps, photographs, and illustrations from Punch, Doyle and Foster demonstrate the challenge that the Somme represented for Kitchener's Army. They conclude Chapter Four with the following sentence ~

"The story of Kitchener's Army does not end with the 151 days of the Somme, but there the youthful army came of age—and it would face the challenges of 1917 head on" (p. 197).

The final chapter, "End of an Experiment", is shorter than the previous ones. It describes how the social experiment of locally raised battalions of volunteers met the reality of modern warfare - and how so many did not make it across no-man's-land. Their bodies remained in France, as a symbol of patriotism and sacrifice. The lack of experience of the men and their leaders took its toll. The chapter ends with the statement "one thing is clear: the road to the Somme paved by Kitchener's Army continued on to the victory of the citizen army in November 1918" (p. 204).

The photograph of one of the men on the final page says it all:

Charlie Branston was wounded by shellfire in the trenches at Contalmaison on 10 July 1016, and killed in action on 12 October 1916 near Lesboeufs. His name is among the thousands recorded on the memorial to the missing of the Somme at Thiepval.

Kitchener's Army includes a wide variety of documentary sources, both primary and secondary, is richly illustrated throughout, and meticulously annotated. It is a fine commemoration to the patriotism and sacrifices of the thousands of men who joined Kitchener's Army. They are not forgotten.

Jane Mattisson

Østfold University College, Norway

|

| British Troops Advance Along the Ancre, Late in the Battle of the Somme |

Chapter two, "Kitchener's Men", describes the training of the volunteers, and the production of their uniforms and equipment. Among the many evocative illustrations in this chapter are the photographs of individuals and groups at camp and in training. Equipment was hard to come by and of questionable quality. All the same, the total weight carried by Kitchener's men was between 61 and 65 lbs., which included clothing, arms, ammunition, accoutrements, rations, and water.

Conditions in the camp were far from comfortable, as the postcard text below illustrates:

Down in our blinking camp,

We're always on the ramp,

That's where we cop the cramp,

Through sleeping in the damp. (p. 81)

It is clear, however, that despite the difficult conditions, spirits ran high.

"Pals", the third chapter of Kitchener's Mob, describes how the retreat from Mons in August 1914 spurred on the recruitment campaign as fears grew that the Expeditionary Force would be pushed back to the Channel ports. The Pals concept grew out of this fear along with a subsequent request that the City of London raise a whole battalion of stockbrokers. Two weeks later, a letter from Lord Derby appeared in the Liverpool Echo, addressed specifically to the commercial classes:

It has been suggested to me that there are many men, such as clerks and others engaged in commercial business, who wish to serve their country and would be willing to enlist in the battalion of Kitchener's New Army if they felt assured that they would be able to serve with their friends and not to be put in a battalion with unknown men as their companions. Lord Kitchener has sanctioned my endeavouring to raise a battalion that would be composed entirely of the classes mentioned, and in which a man could be certain that he would be amongst friends (p. 95).

Pals regiments, from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland became a vital part of Kitchener's Army. A particularly moving photograph reproduced in the chapter is that of Private 15/1545 Tom Scawbord, who was killed on the first day of the Somme on 1 July 1916 (p. 119). The chapter also describes recruitment in Ulster, showing a photograph of the Ulster Volunteers in 1912; they are a pathetic sight as they march with neither uniforms nor ammunition.

Chapter Four, "The Somme", is richly illustrated with photographs from the front, showing the trenches, dugouts, labor battalions, and German barbed wire. There are also extracts from letters such as the one below, which makes it clear that soldiers found it difficult to describe what it was really like at the front:

It is awfully cold and dismal at nights. I would refer you to Rudyard Kipling for a description of the dawn and the close of the day, when soldiers stand to arms, to give you a truer idea of something no-one but a good poet can describe (p. 174).

The chapter also contains a section on Gallipoli and Egypt.

"The story of Kitchener's Army does not end with the 151 days of the Somme, but there the youthful army came of age—and it would face the challenges of 1917 head on" (p. 197).

|

| Pvt. Charles Branston |

The photograph of one of the men on the final page says it all:

Charlie Branston was wounded by shellfire in the trenches at Contalmaison on 10 July 1016, and killed in action on 12 October 1916 near Lesboeufs. His name is among the thousands recorded on the memorial to the missing of the Somme at Thiepval.

Kitchener's Army includes a wide variety of documentary sources, both primary and secondary, is richly illustrated throughout, and meticulously annotated. It is a fine commemoration to the patriotism and sacrifices of the thousands of men who joined Kitchener's Army. They are not forgotten.

Jane Mattisson

Østfold University College, Norway