|

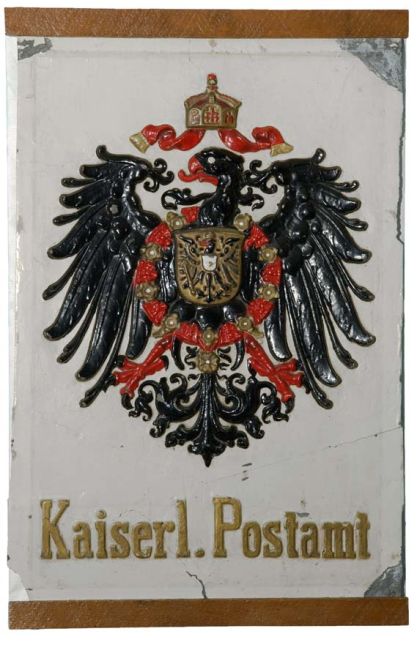

| This German sign from the post office in Apia was acquired by New Zealand soldiers following the capture of German Samoa on 29 August 1914. |

By Karen Cameron and produced by the NZHistory.net.nz team.

When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, Britain asked New Zealand to seize German Samoa as a "great and urgent Imperial service". New Zealand’s response was swift. Led by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Logan, the 1400-strong Samoa Advance Party of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force landed at Apia on 29 August. There was no resistance from German officials or the general population.

Next day Logan proclaimed a New Zealand-run British military occupation of German Samoa. All buildings and properties belonging to the previous administration were seized. In the presence of officers, troops and "leading Native chiefs", the British flag was raised outside the government building in Apia. This was the second German territory, after Togoland in Africa, to fall to the Allies in the First World War.

The Samoan archipelago comprises six main islands, two atolls, and numerous smaller islets located in the southwest quadrant of the Pacific Ocean. Its closest neighbors, the northern members of the Tonga group, are 210 km to the southwest.

|

| On 15 August 1914, the 'Advance Party NZEF' left Wellington Harbor for German Samoa on the troopships Monowai (shown above) and Moeraki. |

Samoans were not consulted when Britain, Germany, and the United States agreed to partition their islands in December 1899. Germany acquired the western islands (Savai’i and ‘Upolu, plus seven smaller islands), while the United States acquired the eastern islands (Tutuila and the Manu’a group) and established a naval base at Pago Pago.

With hindsight, New Zealand’s capture of German Samoa on 29 August 1914 was an easy affair. But at the time it was regarded as a potentially risky action with uncertain outcomes. As it happened, New Zealand had a great deal of luck on its side.

At the outbreak of war, Samoa was of moderate strategic importance to Germany. The radio transmitter located in the hills above Apia was capable of sending long-range Morse signals to Berlin. It could also communicate with the 90 warships in Germany’s naval fleet. Britain wanted this threat neutralized.

After agreeing to seize the territory, New Zealand asked for details of German troop numbers and fortifications. British military intelligence would have been able to report that German Samoa’s defenses were limited to a native constabulary of about 50 men with two European superintendents. (An often-repeated claim that London responded with, "For information regarding the defences of Samoa see Whitaker's Almanac", is now considered untrue.)

New Zealand’s troops were vulnerable as they crossed the Pacific. The ships Monowai and Moeraki, requisitioned from the Union Steamship Company as transports, were slow and unarmed. After sailing from Wellington on the morning of Saturday 15 August, they rendezvoused with HMS Philomel, Psyche, and Pyramus. These aging British cruisers were initially their only escorts.

The danger to the New Zealand convoy was real. At the outbreak of war, Germany had two heavy cruisers, SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau, three light cruisers and various other ships stationed in the Pacific. Throughout the two-week voyage to Samoa, the location of the German East Asia Squadron remained unknown to the Allies.

Naval support was strengthened after five days when the New Zealand convoy reached Noumea in French New Caledonia. There they were joined by the Royal Australian Navy’s battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the light cruiser HMAS Melbourne, and the French armored cruiser Montcalm. In his diary, trooper John Reginald Graham describes the tension on board ship after leaving Noumea:

22 Sat – left [at] daylight & when about 300 miles out sighted steamer in distance but proved to be a British collier… The sighting of this ship caused great excitement as we all thought it was a German…

It was only on reaching Samoa that New Zealand realized the weakness of the German defenses: 20 troops and special constables armed with 50 aging rifles. The single artillery piece at Apia was fired every Saturday afternoon but took half an hour to load. It was later discovered that the German administration had received orders from Berlin not to oppose an Allied invasion.

The Samoa Advance Party of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force landed at Apia on 29 August with no opposition. But had Germany placed greater importance on Samoa, or had the German East Asia Squadron intercepted the New Zealand convoy en route, the story could have been very different.

A fortnight later, on 14 September, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau arrived off Apia and the New Zealand garrison braced itself for large-caliber gunfire. Luckily, the cruisers left once their skippers realized that Samoa was no longer in German hands. They raided Tahiti on 22 September, sinking a French gunboat and bombarding Papeete.

Historian J.W. Davidson described New Zealand rule over Samoa as a "ramshackle administration". German officials were replaced by New Zealand military officers, civilians, or British residents. These often lacked the experience or qualifications to do the job.

As military administrator, Robert Logan governed a population of around 38,000 Samoans and 1500 Europeans (including part-Europeans and about 500 Germans). Samoa’s inhabitants also included 2000 indentured Chinese laborers and 1000 Melanesian plantation workers.

|

| Administrator of Samoa, Colonel Robert Logan |

The political and economic systems established by the Germans were largely maintained, but not strictly enforced. Samoans returned to the ways of fa’a Samoa—Samoan customs and tradition—which the Germans had vigorously suppressed.

Germany was stripped of its colonial territories following its defeat by the Allies in the First World War. In 1920 the League of Nations allocated German Samoa to New Zealand as the mandate of Western Samoa. The territory kept this name when it regained its political independence in 1962.

Despite some complaints, New Zealand’s wartime occupation of Samoa was largely uneventful. The same could not be said of the postwar years. In late 1918 Western Samoa was devastated by an influenza pandemic which killed up to 8500 people—a staggering one-fifth of the population. The 1920s saw the rise of an independence movement, the Mau, which opposed New Zealand rule. Its campaign culminated in the terrible events of "Black Saturday", 28 November 1929—the day that New Zealand military police fired upon a Mau demonstration in Apia, killing 11 Samoans.