Right is more precious than peace

Lieutenant Xavier Paul Fluhr (1885–1956) was an officer with the French 38th Army Corps. He was apparently a photographer himself, but his collection of war photographs also contain images seized from German prisoners. Here are a dozen from his collection of over 400 photographs.

|

| Kaiser Wilhelm II Decorating a Wounded Manfred von Richthofen |

|

| Fokker Eindecker E-3 Taking Off |

|

| Crash of German Rumpler Fighter |

|

| Bombs Falling on a Railyard |

|

| Tribute to French Pilot Joseph Vachon, KIA |

|

| Crown Prince Wilhelm Hosting the Tsar of Bulgaria |

|

| Crown Prince Wilhelm at His Headquarters for the Battle of Verdun |

|

| Damaged Reims Cathedral from the Air |

|

| French Lookout Killed at Post and Devoured by Rats |

|

| German Prisoners |

|

| Trenches at Berry-au-Bac, April 1916 |

|

Military Attachés at GQG de Compiègne |

Source: Hérault Department, France, Archives

Karl I was the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy (21 November 1916–11 November 1918). A grandnephew of Emperor Franz Joseph, Karl became heir presumptive to the Habsburg throne upon the assassination of his uncle, Franz Ferdinand. After his accession, he made a series of attempts to take Austria-Hungary out of World War I through secret overtures to the Allied powers. His effort was the first in a series of ill-fated peace initiatives and gestures in 1917.

As early as 1915, in uniform on the Eastern Front and still heir to the throne, Karl was losing his earlier enthusiasm for the war. He let it be known he would be happy if Austria-Hungary concluded a separate peace with Russia status quo ante-bellum. On the eve of his succession he expressed doubts about the endurance of his own army and that peace would have to be concluded in any case when it soon ran out of men. He enthusiastically endorsed a German peace feeler but knew it was doomed because it was “too demanding regarding territorial conquests.” Karl ascended to the throne determined to use his new powers to seek peace. Soon after, he learned of impending food shortages, especially for cereals and potatoes, due to poor harvests, the turmoil in Galicia, and domestic distribution issues. Shortages of all kinds were especially bad in his capital, Vienna. Buried in his accession manifesto is this revealing sentence: “I want to do everything to banish the horrors and sacrifices of the war as soon as possible, and to win back for my peoples the sorely missed blessings of peace.”

With this determination to pursue peace, he chose to act in secret using his own brother-in-law, Prince Sixtus von Bourbon-Parma, a serving officer in the Belgian Army, as the lead intermediary. The core points of the emperor's proposal were a peace based on the restoration and compensation of Belgium, a peace with Russia in return for Russia's declaration that it held no claim to Constantinople, the re-establishment of Serbia with an outlet on the Adriatic, and support of the "just" claims of France in Alsace-Lorraine.

All of Karl's efforts failed because Germany effectively held veto power over any military settlement, resistance from his foreign ministry, and his own refusal to cede the Sud Tyrol (Trentino) to Italy. His secretive effort blew up in the spring of 1918, when French prime minister Clemenceau publicly confirmed the substance of the discussions, much to Karl's embarrassment. Nonetheless, all the would-be peace efforts of 1917 were doomed. The belligerents were not ready for it.

Source: Over the Top, December 2017

Contributed by Steve Miller

Italy's Unknown Soldier lies at Rome's magnificent Victor Emmanuel II Monument, named after the first king of a unified Italy. Officially it's known as Altare della Patria (Altar of the Fatherland), located in the center of Rome.

Italy's Unknown was chosen on 28 October 1921, in the Basilica of Aquileia by Maria Bergamas, mother of Antonio Bergamas whose body was not recovered. She chose the coffin from among 11 unidentified bodies of members of the Italian Armed Forces whose remains had been retrieved from various areas of the front. Passing in front of the first nine coffins, she screamed her son's name and slumped to the ground before the tenth. The bodies not selected were buried at Aquileia's Military Cemetery.

|

| Victor Emmanuel II Monument |

The Unknown lies in a place of honor beneath the statue of the goddess Roma. Official ceremonies take place annually on the occasion of the Italian Liberation Day (25 April), the Italian Republic Day (2 June), and the National Unity and Armed Forces Day (4 November), during which the president of the Italian Republic and the highest offices of the state pay homage with the deposition of a laurel wreath in memory of the fallen and missing Italians in the wars.

He was awarded Italy's highest military decoration, the Gold Medal of Military Valour. On the front door of the internal crypt are words written by King Victor Emmanuel III: "Unknown the name—its spirit dazzles—wherever Italy is—with a voice of tears and pride—they say—innumerable mothers:—it is my son". An honor guard selected from Italy's various armed services is present, alternating every 10 years.

My thanks to Angelo Romano for his assistance. Grazie, Paisano!

|

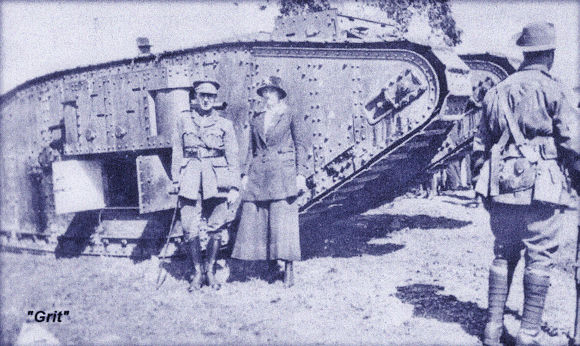

| "Grit"— First Tank to Arrive in Australia |

This title is somewhat misleading, as the book was first published as Pioneers of Australian Armour in the Great War. As such, it is of lesser scope than would otherwise be assumed. That being said, the text is an in-depth look at the beginning of Australian armor, from the first two volunteer-built armored cars (part 1) to the tank used as a crowd-pleasing fund-raiser in-country (part 2).

In early February 1916 the two armored cars were completed, the first a Daimler and the second a Mercedes. Training, staffing, etc. occurred until June, when the group embarked. In August, they arrived in Egypt and were attached to the 2nd Light Horse Brigade.

After patrolling and taking part in the actions in the Libyan desert, the crews switched to light Ford cars with machine guns and thus became the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol. They then patrol and fight in Palestine, are attached to various commands, are stationed at the Dead Sea, and participate in the Battle of Megiddo and the dash to Aleppo. After the Armistice, in January 1919, they battle with Kurdish bandits before going home.

Back in Australia, prior to receiving an actual tank, many different mock-ups were used to raise funds, some somewhat fanciful. When the real tank arrived in July 1918, and the fund-raising really started, the Mark IV female tank was named "Grit" by the wife of the South Australian Governor. Although "Grit" was not used in combat, it wowed the crowds in various cities and brought in many thousands of pounds for the war effort.

As the crews of the armored cars, the light car patrol, and "Grit" were not large, the authors are extremely detailed in the biographies of each crew member. This really gives the reader the flavor of Australian life at the time. The appendices include myriad details concerning the equipment, the timeline of the desert warfare, and even notes on tank driving.

If you are interested in the Anzac desert campaign, this is a wonderfully complete companion to that study.

Bruce Sloan

|

| Cameron Highlanders at Festubert |

After the early 1915 battles of Neuve Chapelle (a British success) and Aubers Ridge (a failure due to inadequate artillery fire), Joffre and Foch continued to put pressure on Sir John

French to continue offensive action. The day after the

failure at Aubers Ridge, and despite the heavy fighting

involving the defense of Ypres by the Second Army,

planning for a further offensive operation on the Artois

front was ordered. The BEF had a manpower shortage

as newly raised divisions were being held in the UK

while decisions were made to send them either to the

Western Front or to Egypt. Despite the shortage of gun

ammunition on the Western Front, French had been

ordered to send much of his 4.5-inch howitzer

ammunition to the Dardanelles and the BEF was

reduced, at one point, to 92 rounds of ammunition for

every rifle.

|

| British Battlefields in Artois Early 1915 |

|

| Captured German Front Line |

Two brothers from Westfield, NJ, today lay in peace side by side at America's Meuse-Argonne Cemetery. Salter and Coleman Clark are one of 21 pairs of brothers buried there. They are unique, however, because they served in the armed forces of separate nations.

The older brother, Salter S. Clark Jr., was drafted into the war in February 1918 and landed in France in June with the AEF. He was brigaded with the British until his unit, the 311th Infantry Regiment of the 78th Lightning Division, was sent to Verdun. He was killed in the Argonne Forest on 1 November 1918.

When the United States entered the war, Asp. Coleman T. Clark attempted to join the American military but was told that his eyesight was too bad. Still determined to aid the war effort, Clark went to the French Army and joined the French Foreign Legion. He was killed in counter-battery fire on 29 May 1918 while attached to the 28th Air Corps of the French Army. He held the rank of aspirant (cadet) when he was killed. He was a recipient of the Croix de Guerre.

Coleman Tileston Clark is buried in Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Plot G, Row 1, Grave 6. His brother is alongside in Grave 7.

Source: ABMC

By Andy Walker, originally presented on BBC Radio 4, 18 April 2013

In January 1913, a man whose passport bore the name Stavros Papadopoulos disembarked from the Krakow train at Vienna's North Terminal station. Of dark complexion, he sported a large peasant's moustache and carried a very basic wooden suitcase. "I was sitting at the table," wrote the man he had come to meet, years later, "when the door opened with a knock and an unknown man entered.

"He was short... thin... his greyish-brown skin covered in pockmarks... I saw nothing in his eyes that resembled friendliness." The writer of these lines was a dissident Russian intellectual, the editor of a radical newspaper called Pravda (Truth). His name was Leon Trotsky. The man he described was not, in fact, Papadopoulos. He had been born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, was known to his friends as Koba, and is now remembered as Joseph Stalin.

|

| Vienna on the Eve of War |

The French frontline soldier of 1914 began morphing into the Poilu or "hairy one" as the war turned into a long slog. The expression has origins in the Napoleonic Wars, and while it explicitly refers to the facial hair that the men in the trenches affected, it suggested some other qualities like virility, self-reliance, the rural background of many of the soldiers, and a propensity to resist authority (grumbling).

The composite image above from Tony Langley's collection show the evolution of the Poilu as presented in French publications.

Contributed by James Patton

The Fullerphone was a portable DC line Morse telegraph, devised in 1915 by Captain (later Major General) A.C. Fuller of the Royal Engineers Signal Service. The important feature of the Fullerphone was that its transmissions were practically immune from being overheard, which made the system at the time very suitable for use in forward areas. In addition, the Fullerphone was very sensitive, and a line current of only 0.5 microampere was sufficient for readable signals. In practice, however, 2 microamperes were required for comfortable readings, and it could be worked over normal Army field lines up to 15-20 miles long. When superimposed on existing telephone lines, telephone and Fullerphone signals could be sent over the line simultaneously without mutual interference. Fullerphone signals were much clearer than those of a "Buzzer telegraph," as the start and end of a signal did not depend on the starting and stopping of a vibrating armature. Hence the potential speed was higher than that offered by the Buzzer telegraph.

|

| Captain A.C. Fuller |

The Fullerphone should not be compared with other DC telegraph systems and Buzzer telegraphs, since its operational principle differed considerably. The Fullerphone employed direct current in the line. By means of a chopping device and a filter circuit the current which flowed into the headphones of both transmitting and receiving Fullerphones was interrupted at an audible frequency (about 400 to 550 Hz). That means that no call could be received (or side tone be heard) unless the chopping device (also known as [the] Buzzer-Chopper) was working and properly adjusted. Therefore the Buzzer-Chopper was always required—whether transmitting or receiving. A filter combination of chokes and condensers prevented any variation in the line current during a signal and suppressed any audible frequency currents produced either by induction from other lines or by a buzzer or telephone speech on the line from passing through the headphones. It also ensured that the rise and fall of line current was comparatively slow and thus prevented "clicks" being heard in the receiver of a telephone set superimposed on the same line. Thus, the Fullerphone could not be overheard either by induction or earth leakage and could only be "tapped" by a similar instrument directly connected to the line. It was found that only with the use of very sensitive equipment, believed to be valve [vacuum tube] amplifiers, was it possible to overhear a Fullerphone, and then only when the listening earth was within 180 feet of the Fullerphone’s earth contact.

Improved models of the Fullerphone were also used in WWII.

From The Imperial War Museum site (with minor editing and emphasis added)

|

| Author M.N. Tukhachevskii |

Developed by the London General Omnibus Company (LGOC), the B-type was the first successful mass-produced motor bus. Introduced in 1910, it was designed and built in London. Within 18 months the LGOC had replaced its entire fleet of horse-drawn omnibuses. By 1913 there were 2,500 B-type buses in service, each carrying 340,000 passengers a year along the capital’s busy roads.

|

| View from the Top |

|

| Note the Side Protection Added in 1915 |

Impact on the Home Front

Many drivers and mechanics were recruited for war service along with their vehicles. This resulted in shortages of both buses and staff on the home front. For the first time women were employed as conductorettes and mechanics to keep London moving.

|

| Home Front Tram and Battle Bus |

[During his tenure] Bismarck did not intend to enter into war against Russia for Austria-Hungary’s interest on the Balkan Peninsula. The German chancellor professed that the stronger party of the alliance must set the pace, noting “within an alliance, there is always a horse and a rider.” Bismarck openly declared that for Germany the casus foederis [for the Dual Alliance] would not extend over the Balkans, and he did not urge cooperation between the German and Austro-Hungarian general staffs or a synchronizing of operative planning.

In his interpretation, the Dual Alliance served to keep Austria-Hungary at a distance from Russia and restrained the czarist empire from either confronting or embracing the Dual Monarchy. Backing up aggressive anti-Russian plans did not fit into this framework at all. Without Bismarck’s approval, any promises on behalf of the German military leadership toward their Austrian colleagues concerning the modalities of a future joint action against Russia were meaningless.When William II was enthroned as emperor of Germany and king of Prussia in 1888, things changed significantly. Two years later, Bismarck, the Iron Chancellor, had to go, and a new German foreign policy was inaugurated. Austria-Hungary’s position in the Dual Alliance had been modified as well. Unlike the Bismarckian era, the Dual Monarchy could perceive distinct evidence of support from Berlin concerning the Balkan affairs. Germany seriously worried about its doomed ally, whose fate seemed to be similar to that of the Ottoman Empire. An active Balkan policy would be needed against this threatening outcome, and Berlin promised full support for such a new course. Germany’s backing up was efficient during the crisis of annexation, and later, to Vienna’s great surprise, its alliance partner declared acceptance of the casus foederis for the Balkans and initiated intense cooperation between the chiefs of the two general staffs. Despite the constant urging of the Austro-Hungarian chief General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, however, again there was no elaboration of a synchronized common deployment. Although the two military leaders agreed to accept the principles of a common strategy based on the plan devised by Alfred von Schlieffen,

the Germans refused to tell the Austrians that in all probability they would have to hold off the mighty Russian army without any significant German contribution.

On the other hand, the deployment of the necessary Austro-Hungarian divisions in Galicia would make it impossible for the Dual Monarchy to realize its most important war aim—defeating Serbia. In fact, war aims of the two allies not only differed from each other but, to some extent, also could be achieved

against each other. The mutual distrust may be explained by this, as well as from the different military strengths of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian

Empire. Moreover, as the international relations grew more unfavorable for the participants of the Dual Alliance, their inter-dependency deepened. Anglo-German antagonism prevented the powers from loosening their bonds to the alliances and seeking connections with members of other coalitions.

On the

eve of the First World War, the Dual Alliance—established as a defensive pact—mutated after 1909 into a bloc, had similarity to the classic movie titled

The Defiant Ones, in which Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis play fugitives shackled together and trying to survive. Each step they take demands cooperation, and this causes serious difficulties for each man. As their inter-dependency increased, it was hardly possible for the stronger party to set the pace, especially

when temporarily ceding power to the weaker member, as happened when William II gave Austria-Hungary a blank check of support in July 1914. As

Günther Kronenbitter, one of the best German experts on the history of German–Austro-Hungarian relations of the time, has written, “despite the fact that it was Austria-Hungary that triggered the Third Balkan War and thereby provoked the outbreak of the Great War, historians interested in the origins of World War I have tended to focus on the system of international relations or on Germany’s role before and during the July crisis. Even today, it seems to be received wisdom among scholars in Germany and elsewhere to consider the Habsburg monarchy as the weak-willed appendix of the powerful German Reich.”

Kronenbitter considers the hesitation of the Austro-Hungarian chief of the general staff to abandon the Serbian campaign and transfer the bulk of the Dual Monarchy’s army to the Galician theater before receiving reliable reports on the Russian general mobilization to be evidence of an attempt to exploit the given situation for setting the pace and carrying out his own war, no matter what happened with the Schlieffen Plan. To be sure, Conrad von Hötzendorf was rather pressed by Austro-Hungarian policymakers to achieve quick military success on the Balkan Peninsula and restore the prestige of the Habsburg Monarchy as a great power. On the other hand, it is true that after writing out the blank check, the German government and the Kaiser showed signs of uncertainty and kept their ally in the dark about unconditional support for an Austro-Hungarian war against Serbia. In Vienna, therefore, one could not know whom to believe—the Kaiser of 5 July or the Kaiser of 30 July, chief of the general staff Helmuth von Moltke or Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg.

Source: "The Dual Alliance and Austria-Hungary's Balkan Policy," Ferenc Pollmann, Multinational Operations, Alliances, and International Military Cooperation: Past and Future, 2005

This month's ST. MIHIEL TRIP-WIRE is dedicated to the story of the 1920 Olympiad, held in Antwerp, which had been occupied for nearly the entire war.

This letter from schoolboy Patrick Blundstone to his father contains a fascinating eye-witness account of the destruction in September 1916 of a Zeppelin airship near Cuffley in Hertfordshire by William Leefe-Robinson, VC.

Dear Daddy,

I hope you are not alarmed, you should not be, unless you know where one of the Zepps went. I have heard that it raided London (up the Strand) and caused heavy causalities. But this I know because I saw, and so did everyone else in the house.

Here is my story: I heard the clock strike 11 o'clock. I was in bed and just going to sleep. Between 2 'clock and 2.30 o'clock, Lily (the servant) woke Miss Willy and told her she could hear the guns. Miss Willy woke Poolman and told him to wake me. He did so. Miss Willy helped Mrs Willy downstairs. We were all awake by now, we had a Miss Blair staying with us for the weekend. We saw flashes and then heard "Bangs" and "Pops".

Suddenly a bright yellow light appeared and died down again. "Oh! It's alright" said Poolman. "It's only a star shell". That light appeared again and we Miss Blair, Poolman and I rushed to the window and looked out and there right above us was the Zepp! It had broken in half, and was like this: it was in flames, roaring, and crackling. It went slightly to the right, and crashed down into a field!! It was about a 100 yards away from the house and directly opposite us!!! It nearly burnt itself out, when it was finished by the Cheshunt Fire Brigade.

I would rather not describe the condition of the crew, of course they were dead - burnt to death. They were roasted, there is absolutely no other word for it. They were brown, like the outside of Roast Beef. One had his legs off at the knees, and you could see the joint!

The Zepp was bombed from an aeroplane above, with an incendiary bomb by a Lieutenany Robertson (Johnson?). We have some relics some wire and wood framework.

The weather is beastly but Mrs and Miss Willy are jolly people, hoping you are all well, love to all. Your loving son Patrick.

Please don't be alarmed, all is well that ends well (and this did for us). We are all quite safe.

Source: The Imperial War Museum Website

World War I German chief of staff Erich von Falkenhayn is a testament to the ability of Western military officers to understand, appreciate, and incorporate will to fight into the planning and execution of military operations. Falkenhayn interpreted every move through the lens of moral force: attack would most likely succeed when enemy will to fight was low and stood a good chance of failure if enemy will to fight was high. Falkenhayn also provides a case study in the failure of tactical-operational intelligence to accurately assess opponent will to fight and a testament to military hubris. While he tried to put Clausewitz’s theories of will to fight into practice, he erred badly at Verdun.

In late 1915 Falkenhayn and the rest of the general staff planned a large offensive near the Meuse River. Their intent was to break French state's will to fight. According to Falkenhayn’s plan, French military defeat would be so terrible and irrecoverable that France would quit the war. This would leave the British at the mercy of what would be a correspondingly larger German Army. Falkenhayn selected the French position at Verdun as the focal point of the offensive. Here the French had unintentionally extended their lines in a broad salient centered on the Meuse heights. This position left the French flanks exposed, and only narrow routes for reinforcement and counterattack. The figure below depicts the battle lines at Verdun between the beginning of the German offensive in 1916 and the limit of German advance. The general direction of the German attack was north to south, or top to bottom in the map. The German plan called for massive artillery bombardments followed by a multi-division ground assault intended to trigger a crushing rout.

|

| Click on Image to Enlarge |

German intelligence backed Falkenhayn’s assessment of French will to fight:

Many French deserters spoke of the war-weariness of the French soldiers and particularly of the adverse effect on French morale of the failure of and the high casualties suffered during the offensives in [1915]. . . . When the French began instituting a defense in depth and leaving their first trench line only lightly defended, German intelligence interpreted this to mean that the French command feared that their troops would break under the German Trommelfeuer [drum fire].

While French will to fight was indeed suffering, the German assessment of French tactical-operational will to fight at Verdun was dangerously exaggerated and arguably wrong. German intelligence officers made two mistakes. First, they failed to account for the French noria system. French Général de Division Philippe Pétain, then commander of the Second Army’s Verdun salient, recognized that French soldiers were suffering from exhaustion. His noria reserve rotation plan was designed to provide soldiers rest, to rebuild their will to fight, and to ensure the Germans would face only fresh troops with strong will to fight.vTo the German intelligence officers, this rotation—designed to improve French will to fight—gave the appearance of thinned lines and weak will.

Second, the Germans assessed that the poor morale (or temporary feelings) of captured French troops amounted to poor will to fight among all French troops. It is generally unwise to extrapolate the unsurprisingly sour disposition of prisoners to the will to fight of active, armed soldiers, at least not without solid corroboration. More important, the Germans took poor individual morale to be an indicator of weak unit cohesion and the unwillingness of the Second Army to hold the line or counterattack. Yet it is possible—even common—to have poor individual will and strong collective, unit-level will to fight. Despite the external appearances given by poor prisoner morale, the French at Verdun were more than ready to hold the line against withering German artillery fire and bayonets. Falkenhayn’s entire plan rested on a false assumption about French will to fight, and the plan failed.

|

| French Poilus at Verdun |

Both sides suffered tremendous losses. French casualties exceeded 300,000. But the Second Army held and Falkenhayn’s plan cost the Germans an equivalent number of casualties: over 300,000. German casualties over ten months at Verdun may have amounted to approximately two-thirds of the entire U.S. Army’s active duty force in early 2018. Many other factors contributed to German failure, including bad weather that bogged down German artillery. Whatever the proximate cause of their tactical defeat, the Germans did not achieve their objectives: Falkenhayn failed to seize Verdun, failed to break French tactical-operational will to fight in 1916, and failed to break French state will to fight. The war went on for another two years, and the losses at Verdun contributed to Germany’s strategic defeat.

Writing about Verdun in his 1919 memoirs, Falkenhayn describes “powerful German thrusts” that had “shaken the whole enemy front in the West very severely” and that had placed doubt in the minds of the Entente partners. French counterattacks were “desperate,” made up of troops collected in “extreme haste.” He estimated German to French casualties at an unrealistic 2:5 ratio. He follows with paeans to German will to fight, and it is abundantly clear throughout his memoir that he had little respect for French fighting spirit. Falkenhayn is to be commended for his genuine appreciation for will to fight as a central factor in war. If he had had a better analysis method to help him understand French will to fight, he might have altered his plans. His hubris and jingoistic vision of Teutonic will to fight made the defeat at Verdun far more likely. Nothing can be done about hubris. Much can be done about will-to-fight analysis.

Source: Will to Fight: Analyzing, Modeling, and Simulating the Will to Fight of Military Units, The Rand Corporation 2018

[Editor's note: The work reviewed here is a little off our usual World War I focus, but it is an important work on military matters that I believe has been grossly neglected because: a) it violates numerous dogmas of political correctness, and b) the author or publisher chose an unfortunate title. MH]

|

| U.S. Marines on the March |