The Pershing Memorial Lecture of 2018

Presented by Scott Stephenson

The Pershing Memorial Lecture of 2018

Presented by Scott Stephenson

(Note: Most sources I've consulted list the death rate at Western Samoa as 24%... This article, cites 22% In any case, I think you will find it quite informative. MH)

In New Zealand governed Western Samoa—not including the adjacent territory of American Samoa—30% of the men, 22% of the women, 10% of all children died from the Spanish Flu.

The global influenza pandemic came to Western Samoa on board an island trader, the Talune, on 4 November 1918. The acting port officer at Apia was unaware that there was a severe epidemic at the ship's departure point, Auckland. On board were people suffering from pneumonic influenza, a highly infectious disease already responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths around the world. Although the Talune had been quarantined in Fiji, no such restrictions were imposed in Samoa.

|

| Steamship Talune |

As a result he allowed passengers ashore, including six who were seriously ill with influenza. Within a week, influenza had spread throughout the main island of Upolu and to the neighboring island of Savai'i. The disease spread rapidly through the islands. Samoa's disorganized local health facilities and traumatized inhabitants were unable to cope with the magnitude of the disaster and the death toll rose with terrifying speed. Grieving families had no time to carry out traditional ceremonies for their loved ones. Bodies were wrapped in mats and collected by trucks for burial in mass graves.Approximately 8500 people—more than one-fifth of the population—died.

The influenza pandemic took a terrible toll on Samoa’s population. In a single week, the prominent businessman and community figure O.F. Nelson lost his mother, one of his two sisters, his only brother, and a daughter-in-law. S.H. Meredith lost seven close relatives. Of the 24 members of the Fono a Faipule (the colonial legislature), only seven survived the pandemic. The total number of deaths attributable to influenza was later estimated as 8500, 22% of the population. According to a 1947 United Nations report, it was "one of the most disastrous epidemics recorded anywhere in the world during the present century, so far as the proportion of deaths to the population is concerned."

|

| The One-Week Toll on the Nelson Family |

Responsibility for the pandemic clearly lay with New Zealand. In 1918, Western Samoa was still occupied by New Zealand forces that had seized the German colony at the beginning of the First World War. In addition to not placing the Talune under quarantine, the New Zealand Administrator, Colonel Robert Logan, did not accept an offer of assistance from the Governor of nearby American Samoa that may have reduced the death toll. A Royal Commission called to enquire into the allegations found evidence of administrative neglect and poor judgement. Logan seemed unable to comprehend the depth of feeling against him and his administration. He left Samoa in early 1919 and did not return. His successor, Colonel R.W. Tate (1920–23), was faced with immense grief and ongoing resentment.

The influenza pandemic had a significant impact on New Zealand's administration of Samoa. Many older matai (chiefs) died, making way for new leaders more familiar with European ways. For survivors, the incident was seared into memory. It became the foundation upon which other grievances against the New Zealand authorities would be built. In 2002, New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark made an official apology to the Samoan people for the actions of the New Zealand authorities. Western Samoa had become an independent republic in 1962 and in 1997 adopted the name Samoa. The U.S. Territorial possessions in the Samoan Islands are known as American Samoa.

Sources: New Zealand History; Journal of Pacific History

|

| Captain Krueger, Returned to His Permanent Rank After His World War I Service |

In his 1995 article, "General Walter Krueger and Joint War Planning, 1922-1938," retired U.S. Army Officer George B. Eaton, discusses the contributions of AEF veteran Walter Krueger to the planning of War Plan Orange, the strategy for defeating Japan in the Pacific Theater in a future struggle. The eventual campaign in the Pacific closely followed the final form of Plan Orange (except the atomic bomb). Krueger was greatly guided by his earlier experience in the Great War and in the Philippines. Here's some background on Krueger, who was one of the most important officer's in American history but is somewhat forgotten today.

Walter Krueger was born in Flatow, West Prussia, on 26 January 1881. His father died in 1884, and in 1889 Anna Hasse Krueger brought Walter and his two siblings to the United States. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Walter was enrolled in the Cincinnati Technical Institute. He enlisted in the 2d Volunteer Infantry and served in Cuba at Santiago and Holguin. In June 1899 Krueger enlisted in the regular Army. He was posted to the Philippines and fought in several engagements during the Philippine Insurrection, rising to the rank of sergeant. Krueger received a commission in 1901, having passed a written examination in lieu of West Point attendance (a common procedure at the time). After a tour in the United States, which included teaching at the Infantry and Cavalry School, Krueger returned to the Philippines, where he mapped areas of Luzon to the north and east of Manila.

Krueger's career soon settled into the slow grind of the old Army. He was promoted to captain only in 1916, but by the end of the First World War he had spent two tours in France, as a key staff officer of two divisions, the 26th and 84th, chief of staff of the Army Tank Corps, and as operations officer of two different corps, including the one that commanded the occupation troops in Germany from 1918 until 1923, advancing to the rank of temporary colonel. For his service in the war, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 1919. He was then assigned to the second Army War College class convened after the war. After graduation, although now qualified for either General Staff service or higher command, Krueger was retained at the College, first as an instructor and then in the Historical Division. He traveled to Berlin in early 1922 to study German strategy. In April 1923 Krueger began his first tour in the Army War Plans Division (AWPD).

Download the full 23-page article HERE.

|

| Esther -- Champion Ratter with One Hour's Take |

|

| Italian War Dog Kennel |

|

| Dog Sleds atop the Adamello, Highest Battlefield on the Italian Front |

|

| The Popular Wine Ration Delivery Squad |

|

| Austrian Officers with Their Mascot. Every Unit Seemed to Have One. |

|

| Dog Team Exiting an Alpine Fort |

|

| Not in the Alps, But I Couldn't Resist These Guys |

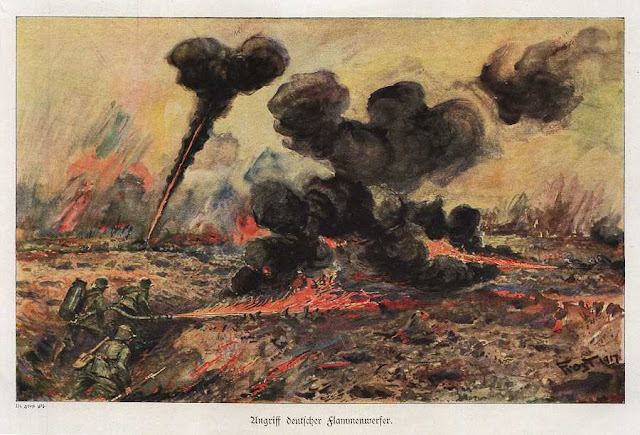

I don't know of a better, or more terrifying, description of what it was like to be attacked by flamethrowers than that contained in Generals Die in Bed. The novel, written by Canadian veteran Charles Yale Harrison, was published in 1930. Critics at the time considered it the finest of the war's semi-autobiographical antiwar treatments. MH

|

| German Flamethrower Teams at the Somme |

They are coming! We look behind us. They have laid down a barrage to cut us off. We are doomed. Anderson jumps from his gun and lies groveling in the bottom of the shallow trench. I tell Renaud to keep firing his rifle from the corner of the bay. Broadbent takes the gun and I stand by feeding him with what ammunition we have left. They are close to us now.

They are hurling hand grenades. Broadbent sweeps his gun but still they come. The field in front is smothered with grey smoke. I hear a long-drawn-out hiss. Ssss-s-sss!

I look to my right from where the sound comes. A stream of flame is shooting into the trench. Flamenwerfer! Flame-throwers! In the front rank of the attackers a man is carrying a square tank strapped to his back. A jet of flame comes from a nozzle which he holds in his hand. There is an odor of chemicals. Broadbent shrieks in my ear: "Get that bastard with the flame." I take my rifle and start to fire. Broadbent sweeps the gun in the direction of the flame-thrower also. Anderson looks nervously to the rear. "Grenades," I shout to him. He starts to hurl bombs into the ranks of the storm troops.

Odor of burning flesh. It does not smell unpleasant. I hear a shriek to my right but I cannot turn to see who it is. We continue to fire towards the flame-thrower. Broadbent puts a fresh pan on the gun. He pulls the trigger. The gun spurts flame. He sprays the flame-thrower. A bullet strikes the tank on his back. There is a hissing explosion. The man disappears in a cloud of flame and smoke.

To my right the shrieking becomes louder. It is Renaud. He has been hit by the flame-thrower. Flame sputters on his clothing. Out of one of his eyes tongues of blue flame flicker. His shrieks are unbearable. He throws himself into the bottom of the trench and rolls around trying to extinguish the fire. As I look at him his clothing bursts into a sheet of flame. Out of the hissing ball of fire we still hear him screaming. Broadbent looks at me and then draws his revolver and fires three shots into the flaming head of the recruit. The advance is held up for a while. The attackers are lying down taking advantage of whatever cover they can find. They are firing at us with machine guns.

|

| Canadian Trench Closest to Hill 70 |

The capture of Hill 70 in France was an important Canadian victory during the First World War and the first major action fought by the Canadian Corps under a Canadian commander. The battle, in August 1917, gave the Allied forces a crucial strategic position overlooking the occupied city of Lens.

Lieutenant General Arthur Currie took command of the Canadian Corps in June 1917, following the Corps' victory at Vimy Ridge. Replacing British General Julian Byng, Currie was the first Canadian put in charge of the corps, Canada's main fighting force on the Western Front.

|

| German Strongpoint Defending Hill 70 |

|

| Memorial at Hill 70 Under Construction (Opened 2017) |

From All Quiet on the Western Front

Tjaden: Well, how do they start a war?

Soldier #1: Well, one country offends another.

Tjaden: How could one country offend another? You mean there's a mountain over in Germany gets mad at a field over in France?

Soldier #1: Well, stupid. One people offends another.

Tjaden: Oh, that's it. I shouldn't be here at all. I don't feel offended.

From La Grande Illusion

Capt. von Rauffenstein: A 'Maréchal' and 'Rosenthal,' officers?

Capt. de Boeldieu: They're fine soldiers..

Capt. von Rauffenstein: Charming legacy of the French Revolution

Capt. de Boeldieu: Neither you nor I can stop the march of time.

Capt. von Rauffenstein: Boldieu, I don't know who will win this war, but whatever the outcome, it will mean the end of the Rauffensteins and the Boeldieus.

Capt. de Boeldieu: We're no longer needed.

Capt. von Rauffenstein: Isn't that a pity?

Capt. de Boeldieu: Perhaps.

From Sergeant York

Alvin York: Well I'm as much agin' killin' as ever, sir. But it was this way, Colonel. When I started out, I felt just like you said, but when I hear them machine guns a-goin', and all them fellas are droppin' around me... I figured them guns was killin' hundreds, maybe thousands, and there weren't nothin' anybody could do, but to stop them guns. And that's what I done.

From Doctor Zhivago

Yevgraf Zhivago: In bourgeois terms it was a war between the Allies and Germany. In Bolshevik terms it was a war between the Allied and German upper classes—and which of them won was a matter of indifference. . . They [the warring powers] were shouting for victory all over Europe—praying for victory to the same God. My task—the Party's task—was to organize defeat. From defeat would spring the Revolution...and the Revolution would be victory for us.

From The Blue Max

Von Klugermann: Well, aren't you coming [to the enemy pilot's funeral]? It's an order.

Stachel: Why?

Von Klugermann: Because our commanding officer has made it one. He believes in chivalry, Stachel..

Stachel: Chivalry? To kill a man, then make a ritual out of saluting him—that's hypocrisy. They kill me, I don't want anyone to salute

Von Klugermann: They probably won't..

From Lawrence of Arabia

Prince Feisal: The English have a great hunger for desolate places. I fear they hunger for Arabia..

Lawrence: Then you must deny it to them.

Prince Feisal: You are an Englishman. Are you not loyal to England?.

Lawrence: To England and to other things.

Prince Feisal: To England and Arabia both? And is that possible? I think you are another of these desert-loving English.

|

| Lone Pine — 6 August 1915 |

Ah, well! We’re gone! We’re out of it now. We’ve got something else to do.

But we all look back from the transport deck to the land-line far and blue:

Shore and valley are faded; fading are cliff and hill;

The land-line we called “Anzac” . . . and we’ll call it “Anzac” still!

This last six months, I reckon, ‘ll be most of my life to me:

Trenches and shells, and snipers, and the morning light on the sea,

Thirst in the broiling mid-day, shouts and gasping cries,

Big guns’ talk from the water, and . . . flies, flies, flies, flies, flies!

And all of our trouble wasted! All of it gone for nix!

Still . . . we kept our end up – and some of the story sticks.

Fifty years from on in Sydney they’ll talk of our first big fight,

And even in little old, blind old England possibly some one might

But, seeing we had to clear, for we couldn’t get on no more,

I wish that, instead of last night, it had been the night before.

Yesterday poor Jim stopped one. Three of us buried Jim –

I know a woman in Sydney that thought the world of him.

She was his mother. I'll tell her – broken with grief and pride –

“Mother” was Jim's last whisper. That was all. And died.

Brightest and bravest and best of us all – none could help but to love him –

And now . . . he lies there under the hill, with a wooden cross above him.

That's where it gets me twisted. The rest of it I don't mind,

But it don't seem right for me to be off, and to leave old Jim behind.

Jim, just quietly sleeping; and hundreds and thousands more;

For graves and crosses are mighty thick from Quinn's Post down to the shore!

Better there than in France, though, with the German's dirty work:

I reckon the Turk respects us, as we respect the Turk;

Abdul's a good, clean fighter – we've fought him, and we know –

And we've left a letter behind us to tell him we found him so.

Not just to say, precisely, “Good-bye,” but “Au revoir”!

Somewhere or other we’ll meet again, before the end of the war

But I hope it’ll be in a wider place, with a lot more room on the map,

And the airmen over the fight that day’ll see a bit of a scrap!

Meanwhile, here’s health to the Navy, that took us there, and away;

Lord! They’re miracle-workers – and fresh ones every day!

My word! Those Midis in the cutters! Aren’t they properly keen!

Don’t ever say England’s rotten – or not to us, who’ve seen!

Well! We’re gone. We’re out of it all! We’ve somewhere else to fight.

And we strain our eyes from the transport deck, but “Anzac” is out of sight!

Valley and shore are vanished; vanished are cliff and hill;

And we’ll never go back to “Anzac” . . . But I think that some of us will!

Oliver Hogue

____________________________

Oliver Hogue, born in Sydney Australia in 1880 worked as a journalist, achieving recognition for his writing under the pseudonym "Trooper Bluegum" during the First World War. He was born on 29 April 1880 in Sydney and was educated at Forest Lodge Public School. Despite growing up in Sydney, his ability at sports and his skill as a horseman led Hogue to consider himself a bushman and, after completing school, he cycled thousands of miles along Australia's east coast. He worked as a commercial traveller before gaining employment with the Sydney Morning Herald in 1907.

Hogue enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in September 1914 as a trooper with the 6th Light Horse Regiment. Commissioned second lieutenant in November, he sailed for Egypt with the 2nd L.H. Brigade in the Suevic in December. Hogue served on Gallipoli with the Light Horse (dismounted) for five months, then was invalided to England with enteric fever. In 1916 he returned to the Anzac forces deployed in the Sinai and Palestine sector. Oliver Hogue went through the whole campaign of the Desert Mounted Corps, but died of influenza at the 3rd London General Hospital on 3 March 1919. He was buried in the Australian military section of Brookwood cemetery. All through his service produced letters, articles, three books, and this poem, which is his best remembered work.

Sources: All Poetry, Australian Dictionary of Biography

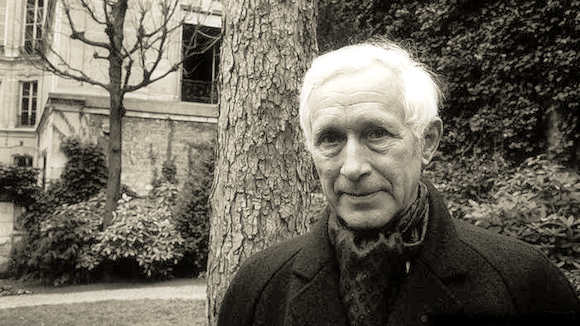

From: "Ernst Jünger: Our Prophet of Anarchy"

Originally Presented in Unherd of The Post

By Aris Roussubis

|

| Ernst Jünger in Paris, 1941 |

It sounds like Jünger's second World War may have been as dangerous for him as his first when he was wounded 14 times. MH

With its modern themes of detachment and alienation, the recent revival of Ernst Jünger’s early work by the internet dissident Right is an understandable urge. When I was a younger man, Jünger’s Storm of Steel, his hallucinatory account of his experiences as a stormtrooper commander in the trenches, was, like Malaparte’s Kaputt and Graves’s Goodbye to All That, a major formative experience in my desire to experience war and, callow though it now sounds, prove myself in it.

Perhaps it’s natural, then, that in later life, the sombre reflections of the middle-aged Jünger as expressed in his recently translated wartime diaries, a husband and father disenchanted with the modern world around him, now seem so compelling.

The diaries open in 1941, with the 46-year-old Jünger serving in an administrative capacity on the general staff of the German army occupying Paris. Initially feted by the Nazi party for the proto-Fascist tone of his early works, Jünger publicly rejected the regime’s advances and came under suspicion as a result, his house searched by the Gestapo and the threat of persecution always hanging over him. A central figure in Germany’s interwar conservative revolution, Jünger, who stated he “hated democracy like the plague,” had come to despise the Nazi regime at least as much. Ultimately, he was far too rightwing to accept Nazism.

Jünger’s intellectual circle had aimed to transcend liberal democracy through fusing Soviet Bolshevism with Prussian militarism, yet the illiberal regime that actually came to power was wholly repugnant to him. “The Munich version—the shallowest of them all—has now succeeded,” he wrote, “and it has done so in the shoddiest possible way,” filling him with dread that Hitler would drive Germany and Europe toward disaster and discredit radical alternatives to liberalism for generations to come.

Jünger’s two closest friends, the National Bolshevik Ernst Nieckish and the philosopher of law Carl Schmitt, each met different fates under the new Nazi order: Nieckish jailed as a dissident until his liberation by the Red Army in 1945 and Schmitt as the regime’s foremost legal theorist. Jünger remained friends with both. For Jünger, the internal exile, dissidence would come in the veiled form of his dreamlike novella On the Marble Cliffs, published on the cusp of war in 1939, in which he predicted the disaster and bloodshed the Nazis would bring in their train. Carefully monitored and shunted off to a desk job in France, Jünger spent his war as a flâneur along the quais of Paris, buying antiquarian books, conducting numerous love affairs, and recording his impressions of the city he loved.

|

| Ernst Jünger at 100 |

A feted intellectual, and a lifelong Francophile, he befriended the city’s cultural elite, socialising with Cocteau and Picasso as well as the collaborationist French leadership and literary figures such as the anti-Semitic novelist Céline, a monster who “spoke of his consternation, his astonishment, at the fact that we soldiers were not shooting, hanging, and exterminating the Jews—astonishment that anyone who had a bayonet was not making unrestrained use of it”. For Jünger, Céline represented the very worst type of radical intellectual: “People with such natures could be recognised earlier, in eras when faith could still be tested. Nowadays they hide under the cloak of ideas.”

While listening to Céline’s ravings about Jews with polite horror, Jünger was embroiled in an affair with Sophie Ravoux, a German-Jewish doctor, and helping to conceal other Jews in hiding, as well as warning the French resistance about imminent deportations. He records the first reports of mass executions in the east, shared among the army leadership, initially with disbelief and then with horror, disgust, and shame. Generals back from the east recount meetings with figures like “a horrifying young man, formerly an art teacher, who boasted about commanding a death squad in Lithuania… where they butchered untold numbers of people,” or share third-hand rumors about “men who have single-handedly slain enough people to populate a midsize city. Such reports extinguish the colours of the day. You want to close your eyes to them, but it is important to view them like a physician examining a wound.”

Continue reading the article HERE.

|

| Constance Markiewicz, Co-Organizer of the 1916 Easter Rebellion, First Woman Elected to the British House of Commons (1918) |

As Roads readers are aware, the impact and history of the Great War extends far beyond the battlefields themselves. The war spawned social upheaval and provided an opportunity for others to make their stand. One of the most famous opportunistic risings was Dublin’s Easter Rising of 1916. That rising is well chronicled in Great War literature, but Women of the Irish Rising: A People’s History approaches it from a new perspective. Author Michael Hogan has skillfully woven the women’s story into that of the overall rising and the Great War in general.

More than other authors of some tomes on the subject, Hogan delves beneath the surface of a nationalistic rising to illustrate the disparate movements that brought it to a boil. There were human rights activists; think Sir Roger Casement, Erskine and Molly Childers; socialists, remember James Connolly; the Celtic revivalists, consider Joseph Plunkett; suffragettes, Margaret Frances Skinnider; labor organizers such as Helena Molony among the multitude of militant activists. Hogan also illustrates how the Great War influenced the rising, more so than the impact the rising had on the war, probably because it was negligible.

The women played a variety of roles including gun shooting warriors in the line, messengers, commissary provisioners, medical workers and whatever needed to be done. Some names are familiar, such as Countess Constance Markiewicz, some, like Nora Connolly, daughter of commander James, were associated with leaders, while others are more obscure, Dr. Kathleen Lynn being an example. It seems that women were more involved in the rising than in many insurrections, reflecting, perhaps both their enthusiasm for the cause and the need for aid from any possible source. Even so, the contrast between James Connolly’s admission of women to his command and their exclusion by other commanders is striking.

|

| Margaret Skinnider (Center) Served as a Sniper and Was Wounded Three Times During the Easter Rebellion |

The book does not end with the surrender. The characters and movements that played roles in the rising are followed to the ends of their lives and into the present day. The historiography of the rising is an interesting reflection rarely found in histories. The text is supplemented by photos, maps, and a bibliography that is most helpful. One thing I really like about the footnotes is the liberal citation of websites with URLs for easy access. The appendices contain a list of known women in the rising, pictures and descriptions of rising related flags and plays, poems and songs of the rising. This work is short, 270 pages in total but, despite my extensive readings on the Easter Rising, I learned new facts about it from these pages. The documentation of the Curragh Mutiny and Sir Roger Casement’s negotiations in Germany place the rising in both local and worldwide streams of history.

I enjoyed Women of the Irish Rising and learned much from it. It encouraged me to look up some of those websites found in the footnotes and to read further. I recommend it both to those seeking an introduction to the rising and more seasoned students looking for a new perspective on this unlikely front in the Great War.

Jim Gallen

|

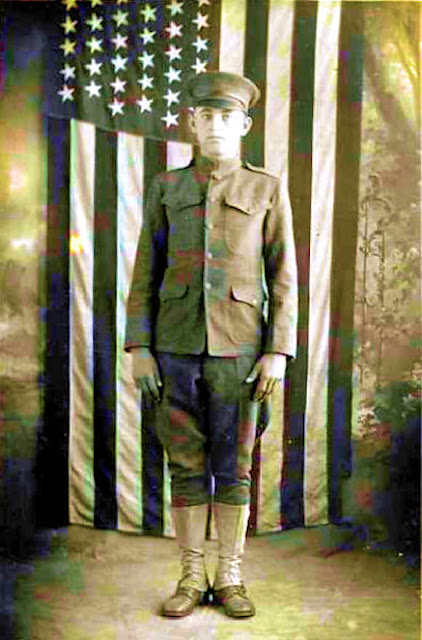

| Harvey Redman, Enlisted 1 August 1917 |

By Master Sergeant Michael Grady, USAF (ret.)

The regiment's Ambulance Company No. 4 arrived in Siberia on 14 September 1918. Its normal staffing was one officer and 130 enlisted men. Of the enlisted personnel, 65 men were detached for service with troops guarding the railroad on the Spasskoe-Razdelnoe sectors, about half this number being posted on duty at the Khabarovsk Hospital from November 1918 to June 1919.

|

| The 27th Infantry on Parade, Khabarovsk, Siberia |

The full complement of animal-drawn wagons and ambulances along with the required number of animals (128 mules and 96 horses) arrived with the company. The wagons were old and worn and already needed repairs. This situation was aggravated by the bad roads of Siberia. Consequently, there were never more than six ambulances in commission at any one time.

By May 1919, all ambulances and teams in serviceable condition—motorized and mule driven—were transferred to Evacuation Hospital No. 17, Vladivostok, although many had already been condemned as unfit for human transport. Three motor ambulances donated by the American Red Cross, furnished nearly all ambulance transportation for the last two months of the expedition's stay in Siberia.

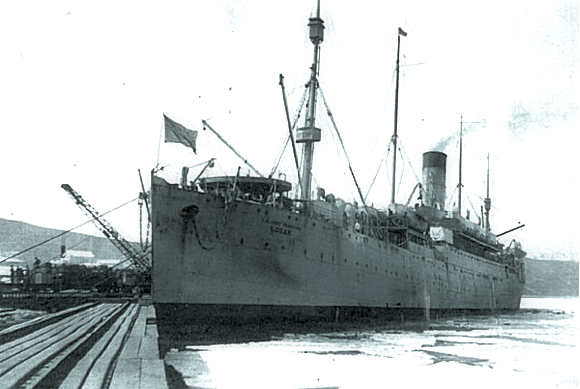

|

| Transport Home: the USAT Logan |

Eventually, the American Siberian expedition was liquidated, and Harvey left for home on the troop transport, USAT Logan, on 11 September 1919. After arriving in San Francisco on 19 October, he was discharged and made his way home to Illinois. He soon settled in Decatur, where he worked at the Borg-Warner Iron Works for most of his life, while also working his farm. My grandparents Fredia Long and Harvey Redman were been married on Christmas Eve 1919 and would have six children, two boys and four girls. He stayed in touch with his closest friend from the Siberian deployment, Ross Umphres of Walla Walla, WA, for the rest of his life and had a reunion with him in 1950 they both treasured. Harvey passed away in November 1968.

As a tribute to my grandfather, I decided to create this model of one of his Siberian ambulances. When I was young, my grandfather farmed with his two mules despite have a new tractor, so one day I got the courage to ask why he did it the hard way. He said "Boy, anyone can drive a tractor, but a matched set of mules are hard to come by, and being man enough to handle them is even harder." The model's mules bear the names of four that granddad cared for: Tobe and June, the leaders, Kit and Joe, the wheelers.

Most wars are wars of contact…ours should be a war of detachment. We were to contain the enemy by the silent threat of a vast unknown desert…

T.E Lawrence

|

| Lawrence with Arab Irregulars |

I found this nice clear evolution of T.E. Lawrence's strategy in the Arab Revolt in the publication Small Wars Journal. The full article (HERE) was written by brothers Capt Basil Aboul-Enein, USAF and Commander Youssef Aboul-Enein, U.S Navy.

Lawrence ends his thesis summarizing rebel warfare as “granted mobility, security (in the form of denying targets to the enemy), time, and doctrine (the idea to convert every subject to friendliness), victory will rest with the insurgents, for the algebraical factors are in the end decisive, and against them perfections of means and spirit struggle quite in vain.” The common dispositions in Lawrence‟s work seem to list the following requirements for a successful guerilla campaign: an unassailable physical or emotional base; a relatively friendly local population; mobility, flexibility and endurance; the ability to inflict damage on the enemy‟s ability of communication; and, lastly, an enemy too few in number to successfully occupy the territory of concern. . .

According to historian Lawrence James, Lawrence did not invent the concept of the Arab guerrilla war, although after the war he provided it with an elaborate intellectual justification in terms of military theory. The idea of utilizing Arab irregulars as guerrillas was originated before the start of the revolt. Major Bray, an Indian officer who had served in Hejaz, Sir William Robertson, the chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Austen Chamberlain, Secretary of State for India, discussed the idea in November 1916. Robertson opened the exchange stating, “I hear you are one of those fellows who think the Arab is no damn good at all?” “No sir, I think that you cannot expect them, in their present state of organization, to hold trenches against disciplined troops, but as guerrilla fighters they will be splendid.”

If Clausewitz‟s formulation is a classic expression of guerrilla tactics as part of modern warfare, T.E. Lawrence is often credited with the first theoretical contribution to understanding guerrilla warfare as a political movement furthered through unconventional tactics rather than as a military tactic supplementary to conventional warfare. According to Lt Col Frederick Wilkins, Lawrence “almost converted the tactics of guerrilla warfare into a science and claimed that no enemy could occupy a country employing guerrilla warfare unless every acre of land could be occupied with troops.”

He elaborates, “in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence explained the plan that eventually defeated the Turks in Arabia. In the Turkish Army, materiel was scarce and precious, men more plentiful than equipment…the aim should be to destroy not the army but the materiel. Eventually, 35,000 Turkish causalities resulted from the new change in methods, but they were incidental to the attack on enemy material. The plan was to convince the Turks they could not stay, rather than to drive them out. The Turkish position gradually became impossible in Arabia. Garrisons withered and the effectiveness of the Turkish field force was largely on paper as the necessity for feeding the scattered units placed a heavy drain on the already burdened enemy supply system.”

Source: "A Theoretical Exploration of Lawrence of Arabia’s Inner Meanings on Guerrilla Warfare," Basil Aboul-Enein and Youssef Aboul-Enein, 2011, reprinted at Smallwarsjournal.com, 2011

|

| Russian Field Cemetery |

|

| Tsar Nicholas in Command at Army Headquarters |