By Christopher Warren

“The strategic air offensive is a means of direct attack on the enemy state with the object of depriving it of the means or the will to continue the war.” This definition of strategic bombing, supplied by Sir Charles Webster and Noble Frankland writing about the Second World War, is no doubt applicable to the Great War as well. Deprivation of the means, i.e. war material and supplies, and the will, i.e. specifically targeting civilians in an attempt to damage public morale was legitimized during the First World War. Although the Napoleonic Wars are often cited as the first example of “total war,” the Great War from 1914–1918 was truly the first war where civilians located hundreds of miles from the warring armies came under attack.

Strategic bombing of cities and civilians by aerial means was not a new concept in 1914. Beginning with the Montgolfièr experiments with manned flight in 1783, the possibility of using balloons and eventually heavier than air machines for military use was envisioned. Initially used as observation posts and artillery spotters, the idea of using airships and aircraft offensively soon found enthusiasts. It was not until the advent of the internal combustion engine, however, that the potential of aerial bombardment from a controlled platform became realistic. In an 1893 letter to the chief of staff of the German Army, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, developer of the rigid airship that would bear his name and theorist on strategic bombing, wrote that his machine could perform not only observation and transport roles, but also “bombard enemy fortifications and troop formations with projectiles.”

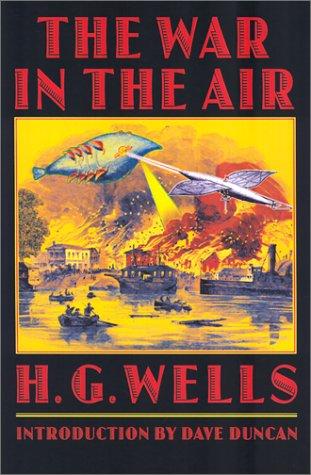

In popular literature and science fiction, the inevitability of airships cruising over cities and dominating future warfare was a popular topic by the late nineteenth century. Jules Verne, no stranger to prescient fiction, wrote in his 1887 story "Clipper in the Clouds" about an aerial battle between two airships loosely resembling the German dirigibles of the First World War. However, it was H.G. Wells who envisioned the strategic bombing of population centers in the future. In his 1908 novel The War in the Air, Wells described a scene in which a fleet of German airships bombed New York City, eerily predicting the fear and terror felt by the public in London and Paris during the Great War. As the historian Lee Kennett argued, so profound and persuasive at capturing public attention was this type of futuristic literature around the turn of the century, that by the time reliable airships and aircraft finally appeared en mass, “extravagant and impossible things would sometimes be expected of them.” During the war, dirigibles and aircraft were seen as an extension of scientific advancement akin to other innovations such as submarines, machine guns, tanks, and poison gas.

So profound were the concerns over the possibility of airborne bombardment, even before the technology to accomplish such a task was near ready, politicians throughout Europe and the United States attempted to regulate aerial warfare. The 1899 Hague Convention, proposed by Russian Tsar Nicholas II in an attempt to regulate armaments and warfare, passed a resolution “agree[ing] to prohibit, for a term of five years, the launching of projectiles and explosives from balloons, or by other new methods of similar nature.”

By the time of the second Hague Convention in 1907, flight technology had changed the possibility and increased the danger of destruction from the air. In 1903 Wilbur and Orville Wright had proved that controlled, powered, heavier-than-air flight was possible with their flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. By the second convention many nations had expressed interest in aviation’s military capabilities, though curiously the United States was at first lukewarm to the idea. Foreshadowing aerial bombardment as a means of “total war,” the 1907 Hague Convention attempted to outlaw strategic bombing of undefended cities and populations.

Because many at the 1907 conference believed it would be easier to restrict bombing to legitimate military targets rather than outlaw it altogether, the Hague agreements concerning land warfare were extended to cover aerial bombardment as well. Since bombing of undefended cities by traditional artillery was already prohibited under Article 25 of the Convention on Land Warfare, conference participants simply changed the article to state “the attack or bombardment, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings which are undefended is prohibited.” The insertion of “by whatever means” into the article was an attempt to extend the prohibition to include aerial bombardment.

Despite its intentions, the language of the article was too vague to be effective and left many questions unanswered. For instance, what was the definition of an undefended town? Did that mean military members were not within town limits or just the absence of soldiers specifically tasked to guard against invasion or bombardment? How could an attacker tell the difference?

Should a city without traditional defenses but housing an arsenal, a military storehouse, or a weapons manufacturing plant really be considered “undefended?” These issues and many others rendered the treaty useless and were routinely cited as justification for strategic bombing of cities when the First World War began.

Although tactical aerial bombing in support of combat operations was employed as far back as 1911 when Italian airplanes dropped the first bombs in combat on Turkish forces in Libya, 1914 saw the first strategic use of bomber aircraft to “strike at the very foundation of the enemy’s war effort-the production of war material, the economy as a whole, [and] the morale of a civilian population.” A few days after the beginning of the First World War, German pilots dropped a few small bombs on Paris in August 1914. In October of that year the British achieved the first substantial strategic success when one airplane destroyed a zeppelin airship in its shed at Dusseldorf, Germany. By December 1914 the Germans were dropping bombs directly on England.

Selected from: "The First Battle of Britain: British Response to German Strategic Bombing in the First World War," Air & Space Journal, Summer 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment