|

| FDR's Diplomatic Passport When He Visited the Western Front in 1918 |

Eighteen days later, three American steamers were all torpedoed, one without warning, and President Wilson called a Cabinet meeting to discuss the issue of war. With tears in his eyes, Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels cast the last vote for war and made the decision unanimous. On 2 April, the president went before Congress to ask for a declaration of war. FDR was seated on the House floor next to his chief. Having been told by the president that "war has been thrust upon us" by the German government and that "the world must be made safe for democracy," Congress rose to thunderous applause. America was now at war.

FDR threw himself into his mobilization duties. When Congress declared war on 6 April 1917, the Navy had slightly more than 60,000 men in its ranks and a meager 197 ships in active service. Within six months, its strength was quadrupled, and by war's end it would have nearly half a million men and over 2,000 ships. Except for sporadic firings on German submarines, the U.S. Navy for the most part did not engage the enemy in World War I. But thanks to its escort duties across the Atlantic, at the time of the armistice the Navy could boast that not one of the troopships that had carried two million Doughboys to the war had been lost on its watch.

Roosevelt was also responsible for Navy supply procurement. He contracted for vast amounts of materiel, sometimes before Congress had even appropriated the money, and he ordered the rapid expansion of training camps and the acceleration of ship construction. FDR was so effective at these tasks that the phrase "See young Roosevelt about it" was often spoken in wartime Washington.

Indeed, Roosevelt was so successful in the procurement arena that a mere two weeks after entry into the war, FDR was called to the White House for an urgent meeting. It seems that the Army chief of staff hadcomplained to President Wilson that "young Roosevelt" had cornered the market on supplies. An amused Wilson told FDR "I'm very sorry, but. . .You'll have to divide up with the Army."

As successful as he was, though, FDR did not want to be behind a desk for the duration of the war. He desperately wanted to see action, not only out of patriotism but because he knew that military service had been a part of cousin Teddy's path to the presidency. Indeed, FDR went to TR and asked the old lion's advice: "You must resign," TR counseled. "You must get into uniform at once."

But both Daniels and Wilson saw it differently. The talents, energy, and decisiveness that FDR brought to his position were indispensable as far as they were concerned. Daniels told Roosevelt that he was "rendering a far more important war service than if he put on a uniform." Army General Leonard Wood, who had gotten wind of FDR's desires to resign, wrote that "Franklin Roosevelt should under no circumstances think of leaving the Navy Department. It would be a public calamity to have him leave at this time." Finally, President Wilson put an end to the matter, instructing Daniels to "Tell the young man to stay where he is."

His disappointment at not being allowed to enlist did not dampen Roosevelt's enthusiasm for his job, however. One of FDR's most notable achievements during this period was his support for the laying of a North Sea mine barrage—a chain of underwater explosives stretching from the Orkney Islands to Norway.

Finally, in the summer of 1918, FDR got his chance to see the war. Secretary Daniels had ordered Roosevelt to go because the Senate Naval Affairs Committee was leaving for Europe soon, and he wanted FDR to get there first and to correct any problems that might raise the ire of the committee. Roosevelt departed for Europe on 9 July 1918 aboard USS Dyer, a newly commissioned destroyer that was rushed into service without a shakedown so it could escort a convoy of troopships across the Atlantic war zone. FDR would consider his trip to Europe during World War I to be one of the great adventures of his life, and many of the stories he told about the trip became more colorful with each telling.

His accounts of events in letters to Eleanor are vivid and detailed, and he delighted in the more adventurous parts of his crossing. For example, two days out of Brooklyn, the convoy hit rough seas, and the Dyer was pitched about. As FDR recounted, "One has to hang on all the time, never moving without taking hold with one hand before letting go with the other. Much of the crockery smashed; we cannot eat at the table even with racks, have to sit braced on the transom and hold the plate with one hand. Three officers ill, but so far I am all right . . . "

There was much excitement the next day too, as FDR's convoy crossed courses at dawn with another American convoy out of Hampton Roads—"a slip-up by the routing officers" as FDR called it. But before the other convoy could be identified as friendly, the Dyer's alert whistle had blown and everyone had manned their gun stations. As the lookout spotted more and more vessels, "we began to wonder if we had run into the whole German fleet." Later the same day, just a few hundred miles from the westerly Azorean island of Fayal, a periscope was reported by the lookout. The Dyer headed for it at full speed and fired three shots from the bow gun. It turned out to be a floating keg with a little flag on it, probably thrown overboard by a passing vessel as a target to train gun crews. But FDR took it in stride, and through the years of retelling the floating keg would become a menacing U-boat that grew closer and closer until FDR himself could almost see it.

|

| USS Dyer at the Azores |

On 14 July, FDR arrived in the Azores, where the next day the Dyer's engines broke down. He spent a day on the island of Fayal, touring the port of Horta and paying a courtesy call on the Governor and British consul. With the engines repaired, the Dyer left for Ponta Delgada, the larger Azorean island where an American naval base was located, and where he met with the admiral in command and toured the facilities. FDR's arrival in Ponta Delgada made such an impression on him that, after returning to the United States, Roosevelt commissioned noted naval artist Charles Ruttan to paint the scene. Roosevelt supplied pictures of the Dyer, photos of Ponta Delgada, and described the scene in detail for Ruttan, even down to which flags were flying on the Dyer and the number and type of support vessels in the harbor at the time. Roosevelt favored this painting so much that he later took it with him to the New York Governor's mansion, to the White House, and finally to his study in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, where he hung it behind his desk, and where it remains to this day.

FDR's convoy finally reached Portsmouth on 21 July, and he proceeded immediately to London by car where he reunited with his staff that had preceded him aboard the Olympic. He spent much of the next week in official meetings with British admiralty officials, touring British and Irish navy yards, and examining British intelligence operations, which he considered "far more developed than ours." He was impressed overall with the British and wrote to Eleanor "I do wish you could see all this in war time: in spite of all the people say, one feels closer to the actual fighting here." He would be even closer soon enough.

On 30 July, Roosevelt had a 40-minute audience with King George V. As he recounted to Mrs. Roosevelt, FDR, and the king "talked for a while about American war work in general and the Navy in particular. He seemed delighted that I had come over in a destroyer, and said his one regret was that it had been impossible for him to do active naval service during the war." After talking at some length about the progress of the land war and the atrocities and destruction committed by the Germans in Belgium and northern France, Roosevelt mentioned that he had spent some time in Germany as a youth and had attended German school. As FDR recalled, the king replied "with a twinkle in his eye" that " 'You know I have a number of relations in Germany, but I can tell you frankly that in all my life I have never seen a German gentleman.' "

The next day, FDR departed for France. Arriving in Dunkirk, Roosevelt saw firsthand the destruction of war. "There is not a whole house left in this place," he recalled. "It has been bombed more than any other two towns put together, in fact." FDR then toured the harbor and an American flying boat base which, by Roosevelt's account, was the first actual American flying base in Europe-a base regularly bombed by the enemy. Upon leaving the base, Roosevelt passed through the city itself where he saw much of the population, " . . .men, women and children, who are still here taking the nightly raids as we would take a thunder-storm, appreciating the danger perfectly but accepting a gambler's chance that the next bomb will hit their neighbor's house and not theirs."

Roosevelt's party proceeded through bombed out Calais, and then spent the night in a country chateau, the headquarters of an American night bombing squadron. During the night, Roosevelt could hear and see the anti-aircraft guns at Calais bursting in the night sky.

FDR's party proceeded uneventfully to Paris where, on 2 August, the assistant secretary had an audience with French President Poincare, and then attended a luncheon in honor of Herbert Hoover, who was hailed has a hero for his efforts to provide relief to persons displaced by the war. Later in the day, FDR met with Premier Clemenceau who declared that every Frenchman and every American were fighting better than the Germans because, as the premier declared, "he knows he is fighting for the Right and that it can prevail only by breaking the German army by force of arms." FDR would later write: "I knew at once I was in the presence of the greatest civilian in France."

|

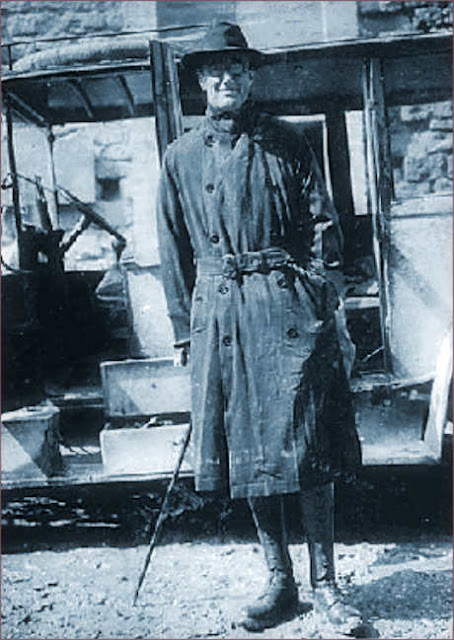

| FDR on the Western Front |

After another day of meetings and dealing with official business, Roosevelt proceeded to the front on 4 August. They passed out of Paris toward Meaux, but their progress was slow. He saw French troops headed toward the front at Chateau-Thierry, as well as Allied wounded and German prisoners being brought the other direction. Meaux itself was congested both with troops and with hundreds of refugees who had fled down the Marne from the front lines. As they proceeded beyond Meaux to ChateauThierry, FDR witnessed one of the horrors of war refugees on the road, not knowing where they were going or if they would have a place to return to. Here is FDR's description of the scene: "They went with big carts drawn by a cow or an ox and a calf trotting behind, bedding, chickens, household goods and children, and some times a grandmother, piled on top."

A few miles from Chateau-Thierry, Roosevelt's party was delayed for an hour by an American artillery train. As they later came over the rise into the valley of the Marne where Chateau-Thierry was located, FDR saw a horrifying sight. "On the ridge to the left lay a wrecked village [likely the village of Vaux on the west side of Hill 204 site of the American monument], four times shelled"—first by advancing Germans, then by the retreating French, then by advancing Americans of the Second Division, and finally by retreating Germans. "This was complete destruction, only detached walls remained. . .We are now in a purely military area."

They proceeded, with some difficulty, to locate the French headquarters, met and had lunch with local commanders, then went on to the eastern edge of Belleau Wood. Everywhere Roosevelt looked, he saw destruction. They walked around and through shell holes, observing "the rusty bayonets, broken guns, emergency ration tins, hand grenades, discarded overcoats, rain stained love letters, crawling lines of little ants and many little mounds, some wholly unmarked, some with a rifle stuck bayonet down into the earth, some with a helmet, and some too, with a whittled cross with a tag of wood or wrapping paper hung over it and in a pencil scrawl an American name." It was a sight he would never forget—one that he would call on many times in the years to come.

Roosevelt's party spent the next several days touring the areas around Chateau-Thierry before proceeding to Verdun, but first they were issued helmets and gas masks. As they descended into the valley of the Meuse, they "came to the sharp turn known as 'L'Angle de Mort', so often described by American ambulance drivers, who passed through there so often by timing the intervals between shells, and where many of them were hit in spite of all precautions." Although the town of Fleury was pointed out to Roosevelt, there was not a brick standing to verify that a town had even existed there. He stopped to take a photograph, but he was hurried along because two German observation balloons had been spotted. As Roosevelt described it, after moving about a quarter mile, "sure enough the long whining whistle of a shell was followed by the dull boom and puff of smoke of the explosion at the Dead Man's Corner we had just left." Roosevelt had come under fire. The motor cars were sent back to conceal themselves, and the party continued their tour on foot. From a ridge, Roosevelt looked out over German and French trench lines, only 40 yards apart, but he could see no signs of life, even though he knew that they were manned at all times. And where there had once been forest behind the lines, there were now only stumps and wasteland.

Thus ended FDR's adventures on the front. The next day he departed for Rome, and then returned to Paris on 14 August. He spent the next three weeks inspecting American air and naval stations before boarding USS Leviathan on 8 September for the trip home. Aboard ship he was hit hard by the Spanish influenza that was sweeping Europe and the United States. His condition was exacerbated by double pneumonia, and Secretary Daniels, who was kept abreast of Roosevelt's condition, telegraphed FDR's mother and wife that they should meet the ship when it docked in New York on the 19th. Roosevelt had to be carried off the ship and taken by ambulance to his mother's house on East 65th Street.

Although FDR would recover from his grave illness, his marriage was changed forever. For, as Eleanor Roosevelt unpacked her sick husband's bags, she discovered letters that proved to her that FDR had had an affair with a young woman named Lucy Mercer. A major step toward reconciliation took place when FDR once again traveled to Europe in January 1919. This time he took Mrs. Roosevelt with him, and they boarded USS George Washington in New York, bound for Paris. Four days into the journey, the Roosevelts were notified that Theodore Roosevelt, Eleanor's uncle and FDR's role model, was dead. Both FDR and Eleanor were stunned. As Mrs. Roosevelt wrote, "Another big figure gone from our nation."

FDR played no part in the peace talks themselves. Rather he had been sent to France to oversee demobilization and the disposal of the Navy's foreign assets. The Roosevelts returned home, again on board the George Washington five weeks later. This time they traveled with President Wilson, who was returning with a draft Covenant of the League of Nations. Because Wilson had for the most part remained in his cabin during the voyage, FDR was surprised to receive an invitation from the president to discuss the League. Later at a luncheon, Eleanor remembered the intensity with which Wilson spoke about the League and that he had said "The United States must go in or it will break the heart of the world. . ."

Back home, Roosevelt settled back into Washington life. He oversaw the completion of the Navy's demobilization and wrestled with the problems caused to the administration by higher prices, unemployment and labor unrest, and a Red Scare. 1919 also witnessed the failure of the Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and President Wilson disabled by a massive stroke.

|

| FDR Visiting Battleship USS Texas, August 1918 |

Early in 1920, FDR was approached by an old friend about the possibility of his being a candidate for Vice President on the Democratic ticket. Well aware that the vice presidency had been on Theodore Roosevelt's path to power, FDR gave his assent. At the Democratic convention later that year, FDR gave a rousing speech in support of fellow New Yorker Al Smith's presidential nomination. Smith's nomination failed, but FDR's speech made an impression. After 44 ballots, the convention finally named James Cox of Ohio its presidential candidate, and Cox selected Roosevelt to be his running mate. Roosevelt was nominated by acclamation.

On 6 August 1920, a month after being nominated, FDR resigned from the Navy Department to campaign for the vice-presidency. Before he did so, he sent the following "All Navy" message to every ship and station:

I want to convey very simply to the officers and men of the Navy my deep feeling at this separation after nearly eight years. I am honestly proud of the American Navy. I am happy too in the privilege of this association with it. No organized body of men in the nation is cleaner, more honorable or more imbued with true patriotism.

We have grown greatly in these years, not merely in size but in right thinking and in effective work. I am very certain that this country can continue to give absolute dependence to the first line of defense. The Navy will carry on its splendid record.

Please let me in the years to come continue our association.

Thirteen years later, FDR would indeed continue his association with the Navy as he acceded to the presidency. He had seen war before, and he would see it again—carrying out the greatest expansion in the Navy's history to fight and ultimately to win a two-ocean war.

Source: Originally presented in the Fall 2011 issue of Relevance: Quarterly Journal of the Great War Society

No comments:

Post a Comment