From Monitor the Journal of the National Marine Sanctuaries

Part I of this article was presented in yesterday's issue of Roads to the Great War

U-140 Attaks a Lighthouse Ship

On August 6, 1918, U-140 attacked the unarmed American steamship Merak, approximately four miles west of the U.S.

Lighthouse Services Light Vessel 71 (LV-71) anchored on the Diamond Shoal Station. Merak was headed from

Newport News, Virginia, to South America with a cargo of coal and was traveling at eight knots when U-140 fired its

deck gun at the ship's bow. Merak's captain quickly turned the ship towards shore and started an evasive zig-zag

course, but the U-boat followed and continued to attack. After a 30 minute chase, the Merak reportedly ran aground

and its 43 man crew launched lifeboats to escape. The entire scene that afternoon played out in full view of the LV-71's

crew. At that time, the vessel's assigned captain, Charles Swanburg, was on liberty, along with two other crew

members, leaving first mate Walter L. Barnett in charge.

Upon hearing the sound of gunfire, Barnett climbed one of the masts and observed smoke in the distance. After

sighting the German U-boat on the surface north of the lightship, Barnett directed the LV-71's wireless (radio) operators

to broadcast a message telling of the attack. The transmission went out using LV-71's call sign, KMSL. It was received

by the American steamer Mariners Harbor and transcribed as follows:

KMSL SOS. Unknown vessel being shelled off Diamond Shoal Light Vessel No. 71. Latitude 35° 05',

longitude 75° 10' (Navy Department 1920:78).

The message transmitted from LV-71 was received by other ships in the vicinity as well. A Lighthouse Service Bulletin

from 1919 stated that 25 vessels heard the warning and sought shelter from possible attack in the Cape Lookout Bight.

U-140 immediately changed course after the LV-71's message was broadcast, leaving the grounded Merak behind, and

made for the light vessel. LV-71 was unable to take any evasive action because it required five hours to get steam up

for its engine and raise anchor. The U-boat soon began shelling LV-71 with its deck guns. The light vessel's chief

engineer, Alonzo Roberts, remarked later that he believed U-140 attacked LV-71 because it had monitored the

transmitted warning (Richmond Times-Dispatch, 15 August 1918).

|

| Diamond Shoals Light Vessel LV-71 |

The U-boat's gunfire soon disabled LV-71’s radio and the ship's destruction was imminent. The 12-man crew hastily

lowered a lifeboat and evacuated the vessel without gathering supplies or saving any of their personal belongings. U-140 continued to fire on LV-71 as the crew rowed west. First mate Barnett recounted that "Finally we could see her go

down in the distance. By then the sub was way out of sight, so I told the boys to pull in the oars, and I mounted the sail,

using the sweep oar for a mast" (Stick 1953:202). The light vessel's crew consisting of two officers, two radio operators,

and eight others left LV-71 around 2:30 p.m. and reached shore a short distance north of the Cape Hatteras wireless

station at 9:30 p.m. After sinking LV-71, U-140 returned to the Merak and sent men with explosives aboard the

abandoned steamer and destroyed the vessel. The U-boat also fired shells at another vessel in the vicinity, the British

steamer Bencleuch, but it escaped.

“Secretary (of the Navy) Daniels said today that undoubtedly the purpose of the submarine commander in

destroying the lightship was to hinder commerce as much as possible. Great volumes of both coastwise and

overseas commerce pass Cape Hatteras both to and from Southern ports, and the German probably believed

that with the lightship gone, some vessels might be wrecked on the shoals (New York Times, 8 August 1918).”

“The attack upon the lightship may represent a new phase of enemy submarine operations off the American

coast, designed to hamper shipping by destruction of important navigation signals. On the other hand, it may

merely represent an isolated case of frightfulness. If the raider has definitely set out to destroy lightships,

exposed light houses and the like, it is believed that he cannot do very extensive harm before his ammunition

supply is exhausted (Macon Telegram, 8 August 1918).”

U-140 remained off North Carolina for several more days after the attacks on Merak and LV-71. On August 10, it

attacked the Brazilian steamer, Uberaba, which radioed for help. USS Stringham, a destroyer, was nearby and hurried

to the scene where it sighted U-140, which quickly submerged. USS Stringham dropped depth charges, but the U-boat

escaped, leaving Uberaba undamaged. U-140 suffered a number of leaks in her pressure hull as a result of the depth

charge attack and began leaking fuel as well. The damage and leaking fuel reduced its operational timeline off the

American coast to a single week before it would be forced to return to Europe. During those seven days, U-140

encountered only one vessel, the naval supply ship USS Pastores, on August 13. The two vessels traded a few shots

before Pastores escaped. Finally, on August 17, with the loss of about 9,000 gallons of fuel, U-140 was forced to begin

the long voyage home.

The cruise back to Germany did not, however, end U-140’s combat activities. On August 22, it engaged the 7,523-ton

armed British merchantman, SS Diomed, in a gun battle and scored its last victory of the war when Diomed succumbed

to the U-boat's gunfire and slid beneath the sea. The next afternoon, U-140 traded salvoes with the armed American

ship, SS Pleiades, but the gathering darkness covered Pleiades' escape forcing U-140 to break off action and resume

its homeward voyage. On September 12-13, U-140 stopped near the Faroe Islands for a fuel replenishment from U-117

and about 5,000 gallons of diesel was transferred from the assisting U-boat. A week later, U-140 re-entered Kiel to end

an 81-day cruise, during which it sunk over 30,000 tons of Allied shipping.

U-117

|

| U-117 Underway |

The next German U-boat to arrive off North Carolina was U-117. Launched on December 10, 1917, with

Kapitänleutnant Otto Droscher in command, U-117 was a UE-II series long-range minelaying U-boat. It was 267.5 feet

long with a cruising speed of 14.7 knots on the surface and seven knots submerged. Its armament consisted of one

deck gun, two mine tubes with a capacity to carry 42 mines, and four torpedo tubes. Departing Kiel shortly after U-140,

it set a course for North America to lay mines off the coast of the United States and to conduct undersea cruiser

warfare. During the voyage across the Atlantic, heavy weather foiled its attempts to attack two lone steamers, two

convoys, and a small cruiser.

U-117 reached the American coast on August 8, 1918, and soon thereafter encountered a fishing fleet off the coast of

Massachusetts. On August 10, U-117 attacked and sunk nine fishing vessels with explosives and gunfire. On August

12, it sighted the Norwegian steamer Sommerstadt and, after observing that the ship was armed, made a submerged

attack that sank the steamer with a single torpedo. The following day, the U-boat made another submerged torpedo

attack and hit the 7,127-ton American tanker, Frederick R. Kellogg, bound from Tampico, Mexico, to Boston,

Massachusetts, with 7,500 barrels of crude oil. The action occurred only 12 miles north of Barnegat Light, New Jersey,

in shallow water, which ultimately enabled the ship to be salvaged.

Later that same day, U-117 began the minelaying phase of its operations by laying mines near Barnegat Light, New

Jersey. Months later, that mine field claimed a victim when the Mallory Line steamship, San Saba, struck a mine and

sank on October 4, 1918. On August 14, U-117 took a break from minelaying operations to resume undersea cruiser

warfare when it encountered the American schooner, Dorothy B. Barrett. The U-boat brought its deck guns to bear and

quickly sunk the sailing vessel. Shortly thereafter, however, the hunter became the hunted when an American seaplane

and submarine chaser SC-71 forced the U-boat to seek refuge beneath the surface. The aircraft subjected U-117 to a

brief barrage of bombs, and SC-71 attacked the U-boat with depth charges before losing track of the submarine.

The next day, August 15, 1918, U-117 resumed its minelaying operations, now off Delaware near the Fenwick Island

Lightship. Later that year in September, mines laid claimed two victims, one damaged and the other sunk. The first

victim was the battleship, USS Minnesota, which struck one of the mines on September 29, and suffered extensive

damage. The cargo ship, Saetia, entered the same field on November 9, struck a mine, and sank.

U-117 continued to move south on August 15, 1918. After laying a third minefield near Winter Quarters Shoal Lightship

off Virginia, U-117 halted an American sailing vessel, the 1,613-ton Madrugada, and sank it with gunfire. Later that day,

a patrolling American seaplane foiled a subsequent attempt by U-117 to stop another sailing ship, and it escaped

unharmed.

On August 16, 1918, U-117 resumed minelaying further south off of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, but the approach of

the 6,978-ton British steamer, Mirlo, interrupted its operation. Approaching the target submerged, U-117 fired a single

torpedo that fatally damaged the steamer off Wimble Shoals. The ship's flammable cargo caught fire and nine of the 52

aboard lost their lives. A heroic rescue effort by U.S. Coast Guard personnel from the Chicamacomico Lifeboat Station

under the command of Warrant Officer John Allen Midgett, Jr., brought the others safely ashore. Following the attack,

U-117 again began laying mines, sowing its fourth and final field. At that point, a shortage of fuel forced the U-boat to

begin making plans to return to Germany. U-117's next and final attack off Cape Hatteras was against the Norwegian

bark, Nordhav, which U-117 sank two days later farther offshore. U-117 then began its voyage back across the Atlantic

to Germany.

After an unsuccessful attempt at a torpedo attack on a lone British steamer, War Ranee, on September 5, 1918, U-117

concentrated on making the final run toward Germany and safety. Three days later, U-117 was contacted over the

wireless by the homeward bound U-140 requesting a fuel replenishment rendezvous due to its critical fuel shortage.

The two U-boats met on September 12 and 13 near the Faroe Islands, and U-140 took on about 5,000 gallons of diesel

before continuing on toward Kiel. U-117 pulled into Kiel rather ignominiously on September 22, having had to call upon

a patrolling torpedo boat to tow it the last leg of its journey having run out of fuel before making it back to port.

The Imperial German Navy recognized the success U-boats were having in United States waters, and planning for

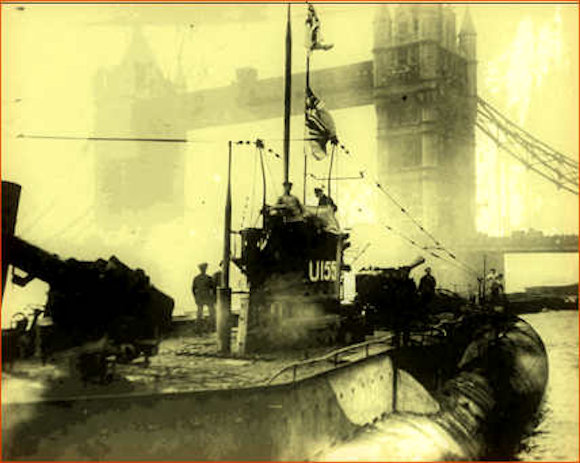

additional U-boat operations continued. Germany was in the process of sending three additional U-boats (U-155,

U-152, and U-139) into U.S. waters when the war ended in November 1918. These U-boats were ordered to cancel

their missions and surrender.

Aftermath

|

| The Surrendered U-155 in London |

The armistice of November 11, 1918 ended hostilities, and required Germany to turn over its U-boats to the Allies. Both

U-140 and U-117 surrendered ten days later in Harwich, England. Over the next few months, the U.S. Navy expressed

an interest in acquiring several former German U-boats to serve as exhibits during a Victory Bond campaign. U-140

and U-117 became two of the six U-boats set aside for that purpose. In March 1919, American crews took over the

U-boats and prepared for the trans-Atlantic crossing under their new task group name, the Ex-German Submarine

Expeditionary Force.

On April 3, 1919, the Ex-German Submarine Expeditionary Force departed Harwich with a group that included the

submarine tender Bushnell, U-140, U-117, U-111, UB-88, UB-148, and UC-97. The captured U-boats made port calls in

the Azores and Bermuda before reaching New York City on April 27, 1919, where they were opened to the public.

Tourists, photographers, reporters, Navy Department technicians, and civilian submarine manufacturers all flocked to

see the war trophies. Then, orders came for U-117 to begin a series of port visits to sell Victory Bonds, during the

course of which it stopped in Washington, D.C., and spent a significant period of time at the Washington Navy Yard.

At

the conclusion of the bond drive later that summer, U-117 was laid up at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, along with U-140

and UB-148. The U-boats remained there, partially dismantled, until the summer of 1921, when U-140 and U-117 were

both selected as target ships. U-117 was selected for aerial bombing tests led by Army Air Force General Billy Mitchell

to demonstrate the value of naval air power against capital ships and was sunk by aerial bombs on June 21, 1921.

U-140 was sunk a month later on July 22, 1921, by the destroyer USS Dickerson. Both U-boats were sunk off Cape

Charles, Virginia.

Thanks to Steve Miller for bringing this material to our attention.

These articles do well in bringing out the details. But one very common misconception ( which is at least implied) is that the term "U-boat" was never used by the allies until early in WW2. All original and un-edited accounts until then just refer to them as "submarines". For instance I have a 1928 edition of "My Mystery Ships" by Q-ship Captain Gordon Campbell VC, and he only ever uses the term submarine. If anyone knows of an exception which has not edited later I would be interested to hear of it.

ReplyDelete