By Tony Langley

Defeats are never particularly endearing to the country suffering them, and since Antwerp was heralded as one of the largest and most stoutly fortified areas in the world, its loss was an embarrassment that no amount of twisting and turning of the events could ever turn into anything but a missed opportunity by the Entente to hold a more northern front line and secure an important industrial area and fortified zone for their use. The loss of Antwerp was one of a series of defeats and setbacks that almost brought Belgium to defeat in 1914 and contributed to the fall from grace of Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty.

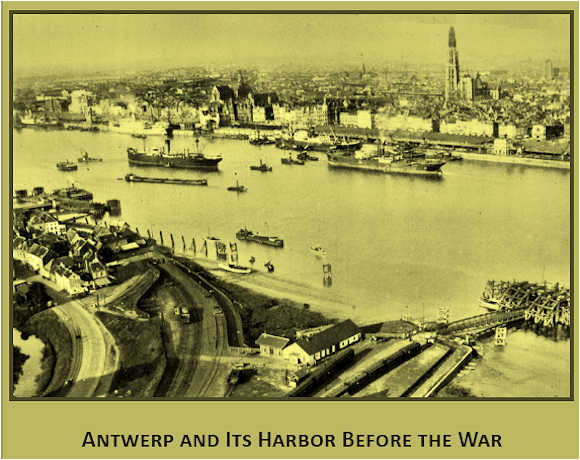

Antwerp, a mercantile city and trading center of great importance since the late Middle Ages had been subject to attacks and sieges countless times, the most recent having taken place in 1831, when, during the Belgian revolution against Dutch rule, the Dutch garrison commander defended the southern citadel against a besieging French army and shelled the city in retaliation with firebombs. This was the cause of many bad memories and protests when in the late 1850s the Belgian government finally decided upon a comprehensive national policy of defense. Belgium, a neutral country, had been guaranteed independence and aid against aggressors by several signatory nations: France, Great Britain, Prussia, Austria-Hungary, and the Russian Empire. The only sensible military policy for a small country such as Belgium would therefore be to fall back on an easily defensible position and await the arrival of a friendly force, most likely one or a coalition of the signatory powers. In 1859 the government decided that Antwerp would have the honor of being the National Redoubt in time of war, a last line of defense in which both the Belgian government and the army would await help from one of the signatory nations that had guaranteed her independence.

Additional smaller defensive positions were constructed at Liège and Namur, while several smaller, older fortifications such as those at Diest, Termonde, Dinant, Huy, Ostend, and other locations were kept in service, these last often being of Napoleonic origin (if not older), and all being outdated by the mid-19th century.

The defenses at Antwerp were conceived on a grand scale. The 1859 plans called for a double circle of fortifications to guard the city and harbor area to the north: an inner ring consisting of an intricate series of bastions, ravelins, water moats, causeways, raised earthen walls covering brick casemates and barracks, artillery positions, supply depots and fortified ornamental city gates controlling entrance and egress, and a second ring of fortifications, some 7 km distant from the city center, consisting of eight brick-built forts, once again encompassing artillery positions, barracks, and depots, built at intervals of 5 km apart to allow mutual artillery support, but otherwise not connected to each other. To the north, south, and west of the city extensive flooding was planned in the event of an attack on the city.

The two encircling rings of fortifications were built during the years 1859–1865, despite ineffectual protest from citizens and merchants alike. It was a showcase example of military architecture, incorporating all the latest advances and techniques. It was built at great cost, and the main contractors, having apparently misjudged the complexity of things, went bankrupt. Nevertheless, the works were completed in the planned time frame.

By 1878 it was already agreed that the fortifications were in need of extension. Artillery range and explosive power increased at a steady pace, and to compensate for this a third encircling series of forts was planned to be built 15 km from the city center, in a great 100 km-long perimeter, which would hopefully keep all vital parts of the city and harbor safely out of enemy artillery range.

The long siege of Port Arthur in the Far East during the Russo-Japanese War of 1905–06 drove home the need for updated and enlarged fortifications if Antwerp were to hold against a modern army. In 1907 the political decision to build the third line of 17 forts, smaller redoubts, and field positions was finally taken and funds allocated by the Belgian parliament. These 17 outer perimeter forts were the most modern then available, built in non-reinforced concrete several meters thick and incorporating almost every modern design and military application then conceivable: revolving retractable steel turrets housing long-range artillery directed by an intricate system of field telephones and forward observers; steel observation turrets; concrete walls and subterranean tunnels; retractable drawbridges; independent electrical power stations in each fort; flood and searchlights positioned on the walls; concrete-protected machine gun positions and powder magazines; positive-pressure ventilation systems to evacuate noxious gases; and supply rooms and infirmaries.

These forts were built in the following years, with most finished by 1912 or 1913, though in August 1914 there was still work to be completed, often involving the fire and control systems and the protection of steel copulas. They were the most modern and up-to-date series of fortifications on the Continent, and, therefore, upon the outbreak of war in 1914, the Belgian government and both France and Britain were confident that even in the face of a determined German assault, the city would be able to hold out indefinitely.

The first German troops crossed the Belgian border on 4 August and started operations against the Liège forts the following day. Initially, the first assaults—overconfident and hurriedly carried out—were repulsed, much to the satisfaction of the newspaper press, especially in Great Britain, which carried overconfident headlines about the resistance of the gallant Belgians. The Belgian government and the king and queen officially relocated to Antwerp upon the occupation of Brussels early in August. By the 10th, however, German heavy artillery was brought to Liège, and when the 420mm siege guns started firing on the 12th, it was only a matter of time before a breach was created in the Belgian fortifications. One by one the forts fell, in one of which, Fort Loncin to the west of Liège, General Leman the Belgian commander at Liège, was knocked unconscious and wounded when the powder magazine of that fort was hit and exploded, all but obliterating almost half of the underground casemates and gun turrets. Overnight, General Leman became the first Entente hero of the war and a symbol of Belgian resistance to the invading German armies.

The Belgian government and the king and queen officially relocated to Antwerp upon the occupation of Brussels early in August. There was no shortage of large buildings to house the ministries and parliament and senate. The Atheneum (or high school) and the grand and ornate municipal ballroom were pressed into service for government use. Hotels, of which there was a multitude in Antwerp for use by businessmen and emigrants awaiting departure to the New World, were soon full to capacity, housing diplomats, officers, journalists, and refugees from all over the occupied parts of the country. The rich and wealthy opened their homes for use as hospitals or nursing stations. The Antwerp Zoo, with many large festival and conference halls, was also turned into a casualty recovery ward, and a number of municipal trams were converted into useful and picturesque Red Cross streetcars, plying the routes from outer fortifications to the city center with wounded and injured soldiers.

No comments:

Post a Comment