|

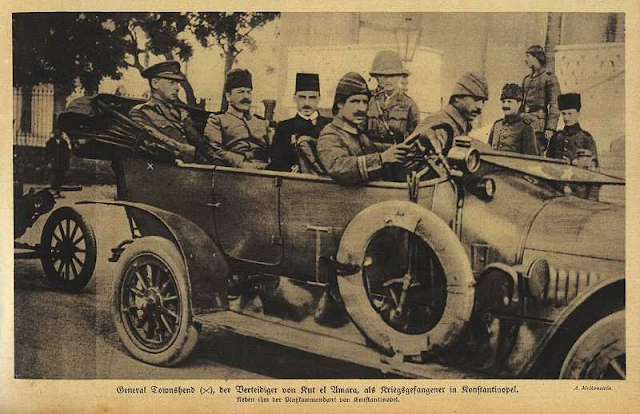

| General Townshend in Custody After the Surrender |

An Excerpt from Armies in Retreat: Chaos, Cohesion, and Consequences, Chapter 3, "Clausewitzian Friction and the Retreat of 6 Indian Division to Kut-al-Amara, November–December 1915 by Nikolas E. Gardner

Overview

In September 1915, Major-General Charles Townshend’s 6 Indian Division, the vanguard of Indian Expeditionary Force D (IEFD), began advancing up the Tigris River with the intent of reaching Baghdad. From 22 to 25 November, however, the division engaged superior Ottoman forces at Ctesiphon, less than 30 miles from its objective. After sustaining heavy casualties, Townshend’s force withdrew from the battlefield on the evening of 25 November. Eight days later, after retreating more than 90 miles downriver with the enemy in pursuit, 6 Indian Division reached the town of Kut-al-Amara, where Townshend halted. Ottoman forces subsequently surrounded the town and established defensive positions farther down the Tigris. Despite multiple unsuccessful attempts by British forces to break through these positions, disease and starvation forced the division to surrender in late April 1916.

. . . Influenced by Townshend’s memoir of the campaign, scholars have assumed that the British commander resolved to seek refuge at Kut-al-Amara during the engagement at Ctesiphon or shortly afterward. If this was the case, then the siege appears to have been a foregone conclusion. Yet a careful assessment of 6 Indian Division’s retreat from Ctesiphon demonstrates that Townshend’s decision to halt at Kut was not preordained. In fact, it was a result of mounting fatigue, ongoing uncertainty about the location of enemy forces, and increasing concern about the morale of Townshend’s own subordinates.

Townshend's Army

|

| Men of the 6 Poona Division with British Officer, Mesopotamia |

To understand Charles Townshend’s decisions during the retreat, it is helpful to become acquainted with the 6 Indian Division commander and the force he led. Fifty-four years old in 1915, Townshend had built his career in British colonial campaigns in India and Africa. He first gained renown as a captain when he led the successful British defense of the Chitral fort in India’s North West Frontier region against a siege by local forces in 1895. Three years later, he commanded an African regiment during the successful British campaign in Sudan. Townshend’s career progressed steadily during the first decade of the twentieth century. By 1911, he had attained the rank of major-general. Townshend proved restless, however, continually lobbying for new opportunities in Britain and India in an effort to gain promotion and acclaim. The outbreak of the First World War appeared to be just such an opportunity. But as commander of the Rawal Pindi Brigade in August 1914, Townshend watched with frustration as other Indian formations embarked on operations to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East while he remained on garrison duty. Thus, when Lieutenant-General Sir John Nixon, the IEFD commander in Mesopotamia, offered him command of 6 Indian Division in the spring of 1915, Townshend seized the opportunity.

Despite Townshend’s extensive imperial service, however, he had little experience commanding the Indian personnel who composed the majority of the division. Each of 6 Indian Division’s three infantry brigades included three battalions of Indian sepoys alongside a single British battalion. Attached to the division was an additional infantry brigade of similar composition, as well as a cavalry brigade comprising three regiments of Indian mounted troops (referred to as sowars), three companies of Indian sappers and miners, six British artillery batteries, and an additional battery of “mixed race” Eurasian personnel. Accompanying the division were an additional 3,500 Indian followers, who performed support functions such as food preparation and animal care. Altogether, Indian personnel comprised more than 80 percent of Townshend’s force.These Indians were members of what colonial authorities termed “martial classes,” ethnic and religious groups that purportedly possessed innate qualities conducive to military service. While British authors attributed different virtues to specific ethnic and religious groups, all the groups shared a willingness to accept colonial rule. Inhabiting rural areas with authoritarian social structures and low rates of literacy, they had little exposure to notions of self-government circulating in India during this period. To reduce the likelihood that these Indian personnel would unite in rebellion, as had been the case in 1857, the British encouraged distinctive dietary and religious practices among the groups they recruited. They also reinforced the identities of individual units by recruiting from specific communities.

Thus, at the outset of the First World War, the Indian Army was a patchwork of distinct units, with entire companies or even battalions consisting of sepoys or sowars as well as non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and Indian Vice-roy’s Commissioned Officers (VCOs), all of the same ethnic and religious background. At full strength, each Indian battalion also included thirteen British King’s Commissioned Officers (KCOs), who served as a vital link between the command structure of the army and the Indian personnel, who were largely illiterate. The unique makeup of Indian units made it difficult for senior British officers to assess the morale of their members. While many had experience commanding Indians, few were familiar with all the languages and cultural practices of the different ethnic and religious groups that comprised the army as a whole. This was particularly true of Charles Townshend. Despite his extensive service in the Indian Army as a staff officer and a senior commander, he had never served as a regimental officer in an Indian unit.

The harsh conditions IEFD experienced in Mesopotamia increased the uncertainty of British commanders for several reasons. The British logistical system was inadequate, which left British and Indian personnel without tents, clothing, and even boots. Indians, in particular, also suffered due to inadequate food supplies. Traditionally expected to supplement their rations by purchasing food locally, they were unable to do so in Mesopotamia; the food shortages led to outbreaks of deficiency diseases such as beriberi and scurvy. Soldiers also suffered from dysentery and malaria—further complicated because the aforementioned logistical shortcomings left them, as well as those wounded in battle, without adequate medical care. To make matters worse, soldiers who became casualties in Mesopotamia were not immediately discharged back to India, which had long been an expectation of Indians who became sick or wounded on campaign. Those soldiers who escaped death or injury felt keenly the loss of comrades and leaders with whom they had served for years or even decades. The small communities that traditionally provided recruits for specific companies and battalions ran out of able volunteers as the war progressed. As a result, it became increasingly difficult to maintain the cohesion of Indian units. As historian Edwin Latter has explained: “Recruiting was too localized, and specialized, to permit the replacement of wastage without changing the social, and even ethnic makeup of company-level units.”

The British also had trouble finding officers with Indian language skills and experience leading Indian personnel. By the fall of 1915, it had become increasingly difficult to find any replacements for officer casualties in Mesopotamia; an average of only seven British officers remained in each Indian battalion. Sir Walter Lawrence, commissioner of Indian military hospitals in France and England, described the overall impact of these losses in a letter to the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener. Indian personnel, he explained, “have become accustomed to look upon their regiment as a family: they have lost the officers whom they knew, and the regiment, which formerly was made up of well-defined and exclusive castes and tribes, is now composed of miscellaneous and dissimilar elements. . . . This is no longer a regiment. It has no cohesion.” The conditions in which soldiers served in Mesopotamia, along with the impact of sustained casualties, corroded Indian morale as 1915 progressed.

In this context, some soldiers expressed religious objections to the campaign. Muslims comprised approximately 40 percent of the Indian Army at the beginning of the war. Many Sunnis had reservations about fighting against the Ottoman sultan, who they recognized as the spiritual leader of the Muslim world. Shias were reluctant to fight near holy sites like Karbala and Najaf. Reassured by the British that the Ottomans had initiated hostilities, and that they would not attack religious sites, most Muslim soldiers participated in the campaign. But trans-frontier Pathans, whose homes lay in independent tribal territory between India and Afghanistan, were more likely to resist. Religious objections to service may also have been motivated by Pathans’ concerns for the safety of their property and families, which were outside the control of British authorities.

Lieutenant-General Arthur Barrett, Townshend’s predecessor in command of 6 Indian Division, unsuccessfully requested to replace four companies of Pathans twice in early 1915. The fact that the Pathans remained in Mesopotamia increased British concerns about the morale of the entire force. Thus, like any commander assuming a new role in an unfamiliar environment, Charles Townshend experienced real uncertainty as he arrived in Mesopotamia in the spring of 1915. But his lack of experience leading Indian personnel, combined with suspicions about their loyalty, compounded this uncertainty. It would become an acute source of friction under the stress of active operations. . .

Surrender

|

| Prisoner Column After the Surrender at Kut |

Human limitations clearly affected 6 Indian Division’s performance. Soldiers participating in active operations without comrades or familiar leadership were more likely to succumb to the effects of fear, fatigue and hunger. This was apparently the case when soldiers retired voluntarily at Ctesiphon on 22 November, and then engaged in looting at Aziziyah on the 28th. These factors also affected their commander. While Townshend generally maintained his composure at Ctesiphon and during the initial stages of the retreat, the Umm at Tubul engagement and the extended retirement that followed left him both exhausted and anxious. This was evident in Townshend’s unwillingness to allow his subordinates even a brief respite on the afternoon of 1 December for fear that they would be unable to resume the retreat. . .

[Besides poor intelligence regarding the enemy forces] Townshend became more apprehensive as he witnessed scenes of indiscipline at Ctesiphon and during the retreat. Significantly, this indiscipline never spread. Even during the siege that followed, only a small minority of Indian soldiers deserted or committed acts of insubordination. Townshend can be criticized for failing to distinguish between the Indians under his command, but he was not alone. While officers serving in Indian units were expected to possess specific linguistic skills and cultural knowledge, few if any senior commanders were familiar with the numerous languages and cultural traits of the diverse groups that made up the Indian Army. Like many British officers, Townshend relied on generalizations and stereotypes that did little to enhance his understanding of his subordinates. As a result, he grew increasingly uncertain about their morale as the retreat progressed.

For readers who wish to gain a greater familiarity with the WWI's Mesopotamia campaign, we have collected our articles on the subject HERE:

. . .

There were legitimate economic, political, and military objectives for capturing Baghdad. However, General Townshend did not get the support he needed for the troops in many aspects, such as logistics and his lack of understanding of cultural differences, including few English officers representing them. Therefore, the pillars holding the objective to capture Baghdad were crumbling. British command did not understand the risk of their aim in capturing Baghdad. This proved fatal, and the Mesopotamian campaign collapsed.

ReplyDelete