By James Patton

The following is an extract from the History of the 353rd Infantry Regiment 89th Division, National Army September 1917–June 1919, by Capt. Charles F. Dienst and associates, published by the 353rd Infantry Society in 1921. It has been extensively edited for length, style, and clarity.

Click on Image to Enlarge

|

| Ready to Fight Company G, 353rd Infantry |

By the spring of 1918 the 353rd Infantry began to feel quite at home in Camp Funston. The men were now well acquainted… Every Company had its Victrola, and most … a small collection of books. Organizations vied … in their efforts to beautify the Camp. Trees were being planted; sidewalks were in the process of construction... Everybody was feeling fit and enjoying life.

To this home-like atmosphere was added a feeling of security; immediate service seemed out of question… reports kept coming in that ships would not be available for a long time to come. 'It looks as if we are going to do our bit in Camp Funston,' was the general opinion.

All of this ended on May 18th with the receipt of the following:

Send troops now at your camp reported ready and equipped for over-sea service to Port of Embarkation, Hoboken, N. J. Arrange time of arrival and other details directly with the Commander of Port. Have inspections made to determine if Organizations and individuals are properly supplied with serviceable clothing, equipment and medical supplies. Report of result shall be made by telegram. Leave all alien enemies behind.

The last instruction included conscientious objectors.

An enormous task was figuring out what to take, packing it all and then returning or disposing of everything that couldn’t be taken. Everything heading overseas was classified as Light Baggage, Heavy Baggage or Freight, and each had a weight limit. In the end, the "Freight" never made it farther than the warehouses at Gievres.

Enlisted men were allowed no personal gear that couldn’t be classified as Light Baggage, but officers were allowed some additional kit to enable them to match the standard of their British counterparts.

The Supply Company insisted on receipts and Company Commanders signed with fear and trembling. Supply Sergeants were the busiest men in the Camp these days. They emptied barrack bags and "turned in" what they considered disallowed for over-seas service and substituted according to Equipment "C." Sizes ran odd as usual and when the men returned Supply Sergeants were the most unpopular men in the Regiment.

|

| Assembly Base and Embarkation Point |

On May 25th 3,401 soldiers and 111 officers were boarded onto eight trains. Strict secrecy was enjoined upon all, and no letters could be mailed. After five days the men arrived at Camp Mills, near New York City, where they spent a few days while the regiment was reassembled. Many men were allowed a pass to see the sights.

At this time Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood was ordered back to Camp Funston to assume command of the new 10th Division. The history says that the soldiers felt his transfer as the loss of a friend as well as an able commander. Brig. Gen. Frank L. Winn would take command of the 89th Division and in September would be succeeded by Maj. Gen. William M. Wright, who would lead the division through the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Offensives.

|

| New Divisional Commander General Winn |

On June 3rd, 1918, the First and Second Battalions boarded HMS Karmala, the Third Battalion, Headquarters and Company and Regimental Headquarters, on HMS Pyrrhus and the Supply and Machine Gun Companies on HMS Caronia. The ships had been pulled from the India service, and the deck crews were made up of Portuguese and East Indians.

|

| HMS Karmala |

The next morning, June 4th, 1918 found the ships still at the piers, as the firemen had gone out on strike. However there were in the ranks a number of railroad fireman and by 1:30 full steam was up.

The convoy included one British cruiser, several submarine chasers and two sea planes.

The lives of all depended upon strict compliance with ship instructions. No lights were to be shown at night. No rubbish of any kind was to be thrown overboard. No smoking on deck after dark. In addition to the regular guards there would be submarine guards, life boat, and raft crews.

|

| Americans Arrive in Liverpool |

On the morning of June 14th the British escorts came to guide the convoy through the minefields of the Irish Sea and into Liverpool. Evening brought the ships into the harbor. Civilians on the Mersey ferries cheered the soldiers, but the city was dark and there was still one more night to spend aboard ship.

On June 16th a short march brought the men to waiting trains, thirty men to each coach. Each man received a letter of gratitude from the King. After many hours the trains arrived at Winchester, where the men marched four miles in the dark, with heavy packs, to Winnall Down, a British "Rest Camp."

|

| Winnall Down Rest Camp |

Remembering the April 11th order of Sir Douglas Haig: "With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end”, rumors spread that the regiment was being attached to the British.

Camp Restriction was severe; passes to Winchester could be had for groups only and an officer had to accompany each group. No one was allowed to go to London. Censoring was tight. It was impossible to write of what had happened. Instructions forbade the following as "dangerous information": 1. Place where written; 2. Organizations, numbers and movements; 3. Morale and physical conditions of our own or Allied troops; 4. Details regarding supplies.

|

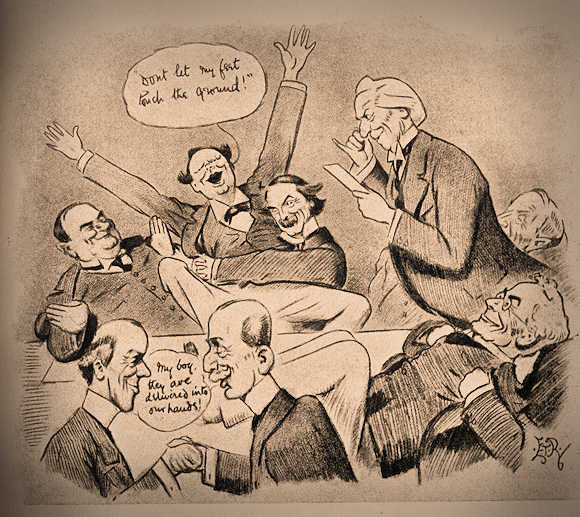

| King Arthur's Statue in Winchester A Doughboy's Effort to Lasso His Majesty Wasn't Well Received |

Orders came to move to Southampton by June 21st.

Never before had the men been so crowded together. There were no sleeping accommodations. That was little hardship, for the violent rocking of the ship soon caused all to seek convenient rather than comfortable quarters. Men who had boasted of weathering the Atlantic now yielded to the humiliating inclination imposed by this little excursion across the channel. Suddenly submarine chasers swarmed around the ship. A sailor upon the bridge is signaling to one of the chasers; how fast he delivers his message. It doesn't seem difficult for him. Darkness begins to set in, and instead of wig-wag flags, blinkers are used.

It suddenly sinks in that there must be something important going on, else why this continued exchange of messages? At the same moment, the ship makes a quick turn, heading back over the course just run, with full steam up. The chaser ahead draws up, and remains. The blackness of night has settled. One after another long streaks of light are brought into play, irregularly criss-crossed as some lead toward the skies while others stretch out over the water. In the distance is visible, at regular intervals, a burst of flame followed by the thunderous boom of the naval guns. An attack is on; evidently submarines. Interest increased as the ship again put out to sea while the excitement of the battle was at its highest. These troops were needed at the front; the men of the Navy would see that they landed safely.

By early morning on the 22nd the ship had landed at Le Havre, directly astern of a large hospital transport that was being loaded with wounded. They were marched uphill to another Rest Camp. ‘German prisoners stopped their work to gaze at the passing columns, and then fell-to again as if they were glad of their present occupation’. In the city, crowds of French children followed, crying, "Biskwee," "Penny," "Souvenir."

|

| An American Unit Marches Off the Le Havre Docks |

Once the division had reassembled, the men were loaded in the "Hommes 40, Chevaux 8" rail cars. No one, not even the Train Commander, knew the destination. For many hours the trains rolled on, through Rouen, within sight of the Eiffel Tower, through Troyes, and to the Reynel Training Area of the American Expeditionary Forces. A month had been spent in making this trip. Nearly 5,000 miles had been covered. Another month and these men from the heart of America would be on the fighting line in France.

Next Friday: The All-Kansas regiment trains for battle.

James Patton