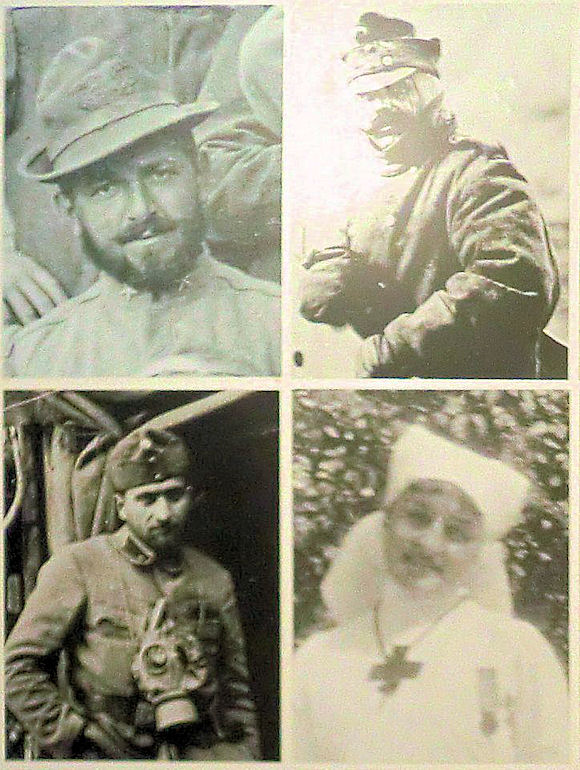

Many of the military museums I've visited commonly have displays—sometimes taking up large walls—that are collages of photo portraits of combatants of all forces who fought nearby. These are always moving. Here are some selections from such a display I found at the Italian Front Museum at Kobarid (formerly Caporetto).

Monday, September 30, 2019

Sunday, September 29, 2019

Marshal Foch's Ten Commandments

1. Keep your eyes and ears ready and your mouth in the safety-notch, for it is your soldierly duty to see and hear clearly; but as a rule, you should be heard mainly in the sentry challenges or the charging cheer.

2. Obey orders first, and, if still alive, kick afterward if you have been wronged.

3. Keep your arms and equipment clean and in good order; treat your animals fairly and kindly and your motor or other machine as though it belonged to you and was the only one in the world. Do not waste your ammunition, your gas, your food, your time, nor your opportunity.

4. Never try to fire an empty gun, nor at an empty trench, but when you shoot, shoot to kill, and forget not that at close quarters a bayonet beats a bullet.

5. Tell the truth squarely, face the music, and take your punishment like a man; for a good soldier won't lie, he doesn't sulk, and is no squealer.

6. Be merciful to the women of your foe and shame them not, for you are a man; pity and shield the children in your captured territory, for you were once a helpless child.

7. Bear in mind that the enemy is your enemy and the enemy of humanity until he is killed or captured ; then he is your dear brother or fellow soldier, beaten or ashamed, whom you should no further humiliate.

8. Do your best to keep your head clear and cool, your body clean and comfortable, and your feet in good condition, for you think with your head, fight with your body, and march with your feet.

9. Be of good cheer and high courage; shirk neither work nor danger; suffer in silence, and cheer the comrades at your side with a smile.

10. Dread defeat, but not wounds; fear dishonor, but not death, and die game; and whatever the task, remember the motto of the division, "It Shall Be Done."

Saturday, September 28, 2019

Friday, September 27, 2019

When the Zimmermann Telegram Was Made Public in the United States

The Decoded Message

Between 1914 and the spring of 1917, the European nations engaged in a conflict that became known as World War I. While armies moved across the face of Europe, the United States remained neutral. In 1916 Woodrow Wilson was elected president for a second term, largely because of the slogan "He kept us out of war." Events in early 1917 would change that hope. In frustration over the effective British naval blockade, in February Germany broke its pledge to limit submarine warfare. In response to the breaking of the Sussex Pledge, the United States severed diplomatic relations with Germany.

|

| Political Cartoonists Had a Field Day with the Telegram |

|

| It was "Arthur" Not "Alfred" |

In January 1917, British cryptographers deciphered a telegram from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German minister to Mexico, von Eckhardt, offering United States territory to Mexico in return for joining the German cause. This message helped draw the United States into the war and thus changed the course of history. The telegram had such an impact on American opinion that, according to David Kahn, author of The Codebreakers, "No other single crypt-analysis has had such enormous consequences." It is his opinion that "never before or since has so much turned upon the solution of a secret message."

In an effort to protect their intelligence from detection and to capitalize on growing anti-German sentiment in the United States, the British waited until 24 February to present the telegram to Woodrow Wilson. The American press published news of the telegram on 1 March. On 6 April 1917, the United States Congress formally declared war on Germany and its allies.

Source: U.S. National Archives

Thursday, September 26, 2019

Pétain: Almost Forgotten

By Leslie Anders

Military Review, June 1954

History almost overlooked Pétain. At the beginning of the fateful year of 1914, he was a colonel of infantry, commanding a line regiment garrisoned at Arras. Then 58, he had been a Regular Army officer for over 35 years and was on the verge of retirement. Indeed, he had already picked out the little house (at St. Omer) in which he would spend his "declining" years.

Among the proverbially agile-minded French, the large and taciturn Pétain never gained much of a reputation as a great thinker. Such indeed is the hard fate of the introvert. Yet, this plodding and painstaking soldier had the independence of to differ with prevailing military doctrines and the moral courage to stand openly—and almost alone against the tide of opinion.

It was just after the turn of the century when the French General Staff assigned Pétain to an instructorship at the small-arms school at Chillons. Originally expecting no difficulties with the soft-spoken newcomer, the staff at Chillons was suddenly shocked to hear him expounding a concept of small-arms employment diametrically opposed to views long held by the French officer corps. Until this time, it had been agreed that the most efficient use of small-arms fire lay in scattering it all along the front. Setting his face against this concept, Pétain argued uncompromisingly for concentration of fire power. So well did he argue his case with his startled colleagues that his embarrassed superiors—anxious to restore harmony on the faculty—offered the heretic a post of his choosing elsewhere.

Before long, the Army tried him again as an instructor, this time as a teacher of infantry tactics at the Ecole Superieure de Guerre. During several years in the classrooms of this famous staff school, Pétain won a complete hearing for his personal views on modern warfare. In his lectures he indulged his advocacy of directed and concentrated fire of all weapons to the fullest. It was largely as a result of Pétain's arguments that the French Army in 1910 accepted the principle of infantry-artillery liaison.

However, Professor Pétain developed other ideas which earned him few friends among those holding the power of promotion over him. To an officer corps passionately devoted to the principle of the impetuous and irresistible offensive brutale à outrance, Pétain frankly preached his defensive heresy: "the salutary fear of enemy fire"; the conservation of manpower; the essential superiority of the defensive; and the efficacy of well-timed counterattacks once the aggressor has worn his ranks thin.

To the vast majority of French officers, this was nothing less than an invitation to disaster. Besides, many protested, it did not accord with the national personality. Pétain's generation had seen the rise of united Germany and the disasters which overwhelmed defensive-minded French armies in the Franco-Prussian conflict of 1870–71. The next time the Germans attack—French officers continually told each other—we Frenchmen will also attack, and the sheer impetuosity and courage of our onslaught will so stagger the methodical Germans that they will not be able to carry through their rigid and complicated plans. Not for Frenchmen this creeping into fortified places and waiting for the German to draw his noose of siege lines around them. Not for Frenchmen what General Joseph Jacques Cesaire Joffre scouted as the "strategical offensive and tactical defensive."

And Joffre, who became commander-in-chief designate in 1911, had prepared a plan to meet the next German aggression against France. Plan XVII represented the last stage of the recasting of French strategy from the defensive-mindedness of the 1870s to the aggressiveness of the 1900s. Where Philippe Pétain found himself as Plan XVII was initiated was discussed in our earlier article:

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

Lloyd George: From the War Office to Prime Minister

|

| Munitions Minister Lloyd George at the Front, 1915 |

In late spring, there was a dramatic shift in the political

landscape. On 5 June Secretary of State for War Horatio Kitchener met a tragic death

when the cruiser HMS Hampshire, on which he was

traveling to Russia, hit a mine in stormy seas and went

down off the Orkneys. Asquith weighed the claims of

several Conservatives before offering the vacant post

to Munitions Minister David Lloyd George. When strategic control passed to the

CIGS at the close of 1915, the office of secretary for

war became little more than a gilded cage, as Lloyd

George well knew, with its duties confined mainly to

army recruiting and departmental administration.

Lloyd George, who had done so much to whittle down

Kitchener's authority, was prepared to move to the

War Office on condition that the original powers of the

secretary for war were restored. As he had no

confidence in either the tactics or strategy of the High

Command, he wanted to be able to formulate military

policy.

But Sir William Robertson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff , backed by Asquith, would not consent to any changes that would rob him of his right to control strategy and act as chief adviser to the government on military matters. Still, Lloyd George may have felt that he could do no more at Munitions, and the War Office was ostensibly a promotion. Besides, the Army was about to launch an offensive at the Somme which, if successful, would enable him to reap much of the credit. After weighing the pros and cons for a week, he accepted the post of secretary of war on the same restricted terms that had been imposed on Kitchener.

Lloyd George spent five unproductive months at the War Office where he chafed at his inability to outwit Robertson and change the direction of the war. Robertson and the generals believed that the war could only be won by defeating the main German army in the west. Lloyd George, on the other hand, considered it sheer folly to continue with costly assaults in France that accomplished nothing. His prescription was to strike Austria, the most vulnerable flank of the Central Powers, and isolate Germany. Clashes between Lloyd George and Robertson were therefore inevitable. Robertson could not match Lloyd George as a debater, but he was at least his equal in the arts of black politics. Time and time again he was able to neutralize Lloyd George's political maneuverings. Robertson was not only skilful in using the press, but, in case of an impasse with his adversary, he could also count on the support of the prime minister and the cabinet.

In September Lloyd George received an unpleasant reminder of what it was like to challenge the British High Command's military policy. During a trip to France he invited one of its leading generals, Ferdinand Foch, to criticize Haig's methods, but Foch had refused to do so. Word of the conversation was leaked to the Morning Post, which hammered Lloyd George for his lack of patriotism and warned him of the consequences if he did not mend his ways. To make matters worse, the battle at the Somme turned out to be a bloody failure, and, since this had occurred on his watch, he could not avoid taking some responsibility. If Lloyd George was at variance with the generals over the direction of the war, he gave every sign in public that he was united with them in his determination to win it. On 26 September he gave his so-called “knockout” interview to Roy Howard, an American reporter, in a bid to throw cold water on President Wilson's anticipated peace initiative. It was reproduced in the Times next day. Lloyd George essentially made public, admittedly in an undiplomatic tone, the cabinet's policy, which was to discourage American mediation for a negotiated peace. He insisted that “the fight must be to the finish—to a knock-out,” however long and whatever the cost, and he warned that Britain would not tolerate the intervention of any state, including neutrals with the highest purposes and the best of motives.

Lloyd George's unhappiness at the War Office

deepened in the autumn of 1916. The war was going

badly for the Allies, and his efforts to circumvent the

obstructionism of the CIGS and the generals had failed.

He could see no ray of light ahead. Pondering on how

to achieve greater civilian control of the generals, he

could think of no other way than to remove the higher

conduct of the war from Asquith's hands. As David

Woodward, a leading authority on the period has

observed, “it was Robertson and the military policy he

represented—not Asquith—whom Lloyd George

hoped to overthrow.”

Lloyd George admired Asquith's intellectual qualities, his skills as a parliamentarian, and the resourcefulness that he had shown as prime minister in times of peace. Indeed, during the prewar era Lloyd George had acted as a creative spark for the Liberal social program and someone on whom Asquith could depend, and the two, however different temperamentally, had formed a very effective team. But tensions in their relationship began to appear in the summer of 1915 owing to their differences over conscription. In the months that followed, the gap between the two became more acute as Lloyd George grew increasingly disillusioned with, and critical of, Asquith's inefficient and leisurely management of the war. Not only did Asquith defer to his generals, he insisted on preserving the cabinet's executive authority. This meant that all major rulings in the War Council and its successors the Dardanelles Committee and the War Committee, were referred to the full cabinet, where too often issues which provoked disagreement were shelved rather than decided on one way or another.

As Lloyd George put more and more distance between himself and Asquith, he forged new links with a number of prominent Unionists. As a group, the Conservatives also wanted greater efficiency and speed in decision-making. They distrusted Lloyd George, however, regarding him as a Welsh radical who in previous years had been a fierce critic of the Boer War. Still they were impressed by his driving force and by his determined approach to waging war, regardless of infringements on individual liberty. In the final analysis they saw Lloyd George as a lesser evil than Asquith.

The press joined restive Conservatives to clamor for reform of the executive. The Morning Post summed up the frustration felt by many with Asquith's ministry when it wrote on 1 December 1916: “Nothing is foreseen, every decision is postponed. The war is not really directed—it directs itself.” There were demands that Asquith be replaced as prime minister by Lloyd George, who seemed better fitted to play the part of a war leader. In short, the country as a whole wanted a change, a livelier organizer of victory, a new Pitt. On 1 December 1916 Lloyd George, with Bonar Law's backing, presented Asquith with a plan that would reconstruct the system for prosecuting the war. This involved delegating executive authority to a small committee consisting of three or four ministers free of departmental responsibilities and under the chairmanship of Lloyd George. Asquith would be excluded from the new body but would remain prime minister. After some modification, Asquith accepted the arrangement. On 4 December, however, a leading article in the Times attacked Asquith personally and implied that he had been reduced to a subordinate position in his own cabinet. The piece was clearly written by someone with good inside information. It appears that Carson was the informant, but Asquith suspected Lloyd George, who was known to have friendly relations with Lord Northcliffe, owner of the Times.

His pride injured, Asquith repudiated his earlier

agreement with Lloyd George, determined to fight.

Lloyd George's response was to resign. Asquith could

have weathered Lloyd George's defection, but

confronted by the loss of all, or nearly all, of the

Conservatives in the cabinet, he had no option but to

resign.

The king immediately sent for Bonar Law, the most obvious choice to succeed Asquith. Bonar Law declined the offer when Asquith made it clear that he would not serve under him. Thereupon the king turned to Lloyd George and invited him to form a government. Lloyd George accepted and from 7–9 December garnered enough support from Conservatives, Labour, and Liberal sympathizers to form a government. His longstanding ambition to succeed Asquith had been achieved, not so much by intrigue as by accident.

This article is a selection from the March 2017 issue of Over the Top

But Sir William Robertson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff , backed by Asquith, would not consent to any changes that would rob him of his right to control strategy and act as chief adviser to the government on military matters. Still, Lloyd George may have felt that he could do no more at Munitions, and the War Office was ostensibly a promotion. Besides, the Army was about to launch an offensive at the Somme which, if successful, would enable him to reap much of the credit. After weighing the pros and cons for a week, he accepted the post of secretary of war on the same restricted terms that had been imposed on Kitchener.

Lloyd George spent five unproductive months at the War Office where he chafed at his inability to outwit Robertson and change the direction of the war. Robertson and the generals believed that the war could only be won by defeating the main German army in the west. Lloyd George, on the other hand, considered it sheer folly to continue with costly assaults in France that accomplished nothing. His prescription was to strike Austria, the most vulnerable flank of the Central Powers, and isolate Germany. Clashes between Lloyd George and Robertson were therefore inevitable. Robertson could not match Lloyd George as a debater, but he was at least his equal in the arts of black politics. Time and time again he was able to neutralize Lloyd George's political maneuverings. Robertson was not only skilful in using the press, but, in case of an impasse with his adversary, he could also count on the support of the prime minister and the cabinet.

In September Lloyd George received an unpleasant reminder of what it was like to challenge the British High Command's military policy. During a trip to France he invited one of its leading generals, Ferdinand Foch, to criticize Haig's methods, but Foch had refused to do so. Word of the conversation was leaked to the Morning Post, which hammered Lloyd George for his lack of patriotism and warned him of the consequences if he did not mend his ways. To make matters worse, the battle at the Somme turned out to be a bloody failure, and, since this had occurred on his watch, he could not avoid taking some responsibility. If Lloyd George was at variance with the generals over the direction of the war, he gave every sign in public that he was united with them in his determination to win it. On 26 September he gave his so-called “knockout” interview to Roy Howard, an American reporter, in a bid to throw cold water on President Wilson's anticipated peace initiative. It was reproduced in the Times next day. Lloyd George essentially made public, admittedly in an undiplomatic tone, the cabinet's policy, which was to discourage American mediation for a negotiated peace. He insisted that “the fight must be to the finish—to a knock-out,” however long and whatever the cost, and he warned that Britain would not tolerate the intervention of any state, including neutrals with the highest purposes and the best of motives.

|

| Another Stop on the Tour of the Front |

Lloyd George admired Asquith's intellectual qualities, his skills as a parliamentarian, and the resourcefulness that he had shown as prime minister in times of peace. Indeed, during the prewar era Lloyd George had acted as a creative spark for the Liberal social program and someone on whom Asquith could depend, and the two, however different temperamentally, had formed a very effective team. But tensions in their relationship began to appear in the summer of 1915 owing to their differences over conscription. In the months that followed, the gap between the two became more acute as Lloyd George grew increasingly disillusioned with, and critical of, Asquith's inefficient and leisurely management of the war. Not only did Asquith defer to his generals, he insisted on preserving the cabinet's executive authority. This meant that all major rulings in the War Council and its successors the Dardanelles Committee and the War Committee, were referred to the full cabinet, where too often issues which provoked disagreement were shelved rather than decided on one way or another.

As Lloyd George put more and more distance between himself and Asquith, he forged new links with a number of prominent Unionists. As a group, the Conservatives also wanted greater efficiency and speed in decision-making. They distrusted Lloyd George, however, regarding him as a Welsh radical who in previous years had been a fierce critic of the Boer War. Still they were impressed by his driving force and by his determined approach to waging war, regardless of infringements on individual liberty. In the final analysis they saw Lloyd George as a lesser evil than Asquith.

The press joined restive Conservatives to clamor for reform of the executive. The Morning Post summed up the frustration felt by many with Asquith's ministry when it wrote on 1 December 1916: “Nothing is foreseen, every decision is postponed. The war is not really directed—it directs itself.” There were demands that Asquith be replaced as prime minister by Lloyd George, who seemed better fitted to play the part of a war leader. In short, the country as a whole wanted a change, a livelier organizer of victory, a new Pitt. On 1 December 1916 Lloyd George, with Bonar Law's backing, presented Asquith with a plan that would reconstruct the system for prosecuting the war. This involved delegating executive authority to a small committee consisting of three or four ministers free of departmental responsibilities and under the chairmanship of Lloyd George. Asquith would be excluded from the new body but would remain prime minister. After some modification, Asquith accepted the arrangement. On 4 December, however, a leading article in the Times attacked Asquith personally and implied that he had been reduced to a subordinate position in his own cabinet. The piece was clearly written by someone with good inside information. It appears that Carson was the informant, but Asquith suspected Lloyd George, who was known to have friendly relations with Lord Northcliffe, owner of the Times.

|

| Lloyd George in Discussions with General Haig and Joffre in 1916 |

The king immediately sent for Bonar Law, the most obvious choice to succeed Asquith. Bonar Law declined the offer when Asquith made it clear that he would not serve under him. Thereupon the king turned to Lloyd George and invited him to form a government. Lloyd George accepted and from 7–9 December garnered enough support from Conservatives, Labour, and Liberal sympathizers to form a government. His longstanding ambition to succeed Asquith had been achieved, not so much by intrigue as by accident.

This article is a selection from the March 2017 issue of Over the Top

Tuesday, September 24, 2019

The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919

By Mark Thompson

Basic Books, 2009

Len Shurtleff & the Editors, Reviewers

|

| Italian Trench, Asiago Plateau |

The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919 is a well-crafted and thoroughly researched overview of Italian participation in the Great War, a subject too often ignored by English-speaking historians. The author's use of "White War" in his title is somewhat misleading. The term usually is a reference to the portion of the war waged in the high Alps, which—though spectacular—was a lesser part of the war on the Italian Front, both in scale and strategically. Thompson's effort is comprehensive. He details all the military events on the Italian Front from the opening of the war there in May 1915 through the armistice of 4 November 1918. He also traces the main outlines of Italian politics, including character sketches of the principal military and civilian actors and the often ham-handed Italian diplomacy of the war.

While the Italian public was overwhelmingly anti-Austrian in the weeks leading up to hostilities, there was no popular groundswell of popular opinion favoring war. Italy had been a member of a Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungry dating back to the 1880s. Seeking to increase its territory, the Salandro government refused to go to war in August 1914. Instead, it opened negotiations with both Vienna and with Great Britain and France seeking to expand Italia irredenta, which reclaimed allegedly Italian territories in the Tyrol, Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, and Dalmatia. While Vienna balked at handing over territory, France and Britain promised everything the Italian irredentists desired and more, including lands in Turkish Anatolia.

Italy was militarily, politically, and economically unprepared for war. Its army was ill trained, ill equipped (particularly in artillery), and badly led. As a largely agrarian nation, it lacked heavy industry. Nonetheless, in May 1915 Italian forces cautiously advanced across the Austrian frontier in the Tyrol and on the Carso Plateau northwest of Trieste. There the front remained static for some 29 months as Italian casualties mounted during 12 major battles along the Isonzo River. The stalemate was not broken until October 1917, when combined Austrian and German forces pushed the Italians back 150 kilometers in the Battle of Caporetto.

The Caporetto defeat provided the catalyst needed to spark a reorganization of the Italian war effort. The Italian high command was purged, treatment of soldiers vastly improved, and new financing made available for expanded domestic munitions production. A year later, with help from England, France, and America, Italy had defeated her Habsburg enemy. In the ten years since its publication, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919 has proven to be the most authoritative work on the Great War's Italian Front.

Revised from the original presentation in the St. Mihiel Trip-Wire, July 2009

While the Italian public was overwhelmingly anti-Austrian in the weeks leading up to hostilities, there was no popular groundswell of popular opinion favoring war. Italy had been a member of a Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungry dating back to the 1880s. Seeking to increase its territory, the Salandro government refused to go to war in August 1914. Instead, it opened negotiations with both Vienna and with Great Britain and France seeking to expand Italia irredenta, which reclaimed allegedly Italian territories in the Tyrol, Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, and Dalmatia. While Vienna balked at handing over territory, France and Britain promised everything the Italian irredentists desired and more, including lands in Turkish Anatolia.

The Caporetto defeat provided the catalyst needed to spark a reorganization of the Italian war effort. The Italian high command was purged, treatment of soldiers vastly improved, and new financing made available for expanded domestic munitions production. A year later, with help from England, France, and America, Italy had defeated her Habsburg enemy. In the ten years since its publication, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919 has proven to be the most authoritative work on the Great War's Italian Front.

Revised from the original presentation in the St. Mihiel Trip-Wire, July 2009

Monday, September 23, 2019

A Twenty-One-Gun Salute to the U.S. Navy in World War I

As part of my effort to update my Doughboy Center website, I've dedicated a major section to the U.S. Navy's effort in the work. I've provided links to 21 excellent articles about America's naval effort in the war. The official painting above, A Fast Convoy: USS Allen Escorting [the troopship] USS Leviathan captures the essential role of the Navy in transporting the AEF to Europe. Here is the list of articles on the subject; below is the direct link to the site.

http://www.worldwar1.com/dbc/ghq1arm.htm#naval

Sunday, September 22, 2019

Ludendorff on Verdun

The Hindenburg-Ludendorff team bore no responsibility for initiating the Battle of Verdun. In February 1916, when Verdun began, they were responsible for the Eastern Front. Hindenburg and Ludendorff, however, in late August of that year were appointed to the Supreme Command. Hindenburg replaced Falkenhayn to become chief of the General Staff and Ludendorff was named his first quartermaster-general. It would be their first priority to deal with the still raging Battles of the Somme and Verdun, which were now bleeding the German Army on the Western Front. Later in his memoir, My War Memories: 1914-1918, General Erich Ludendorff made many astute observations on those battles that are scattered through his somewhat rambling account. Here, thanks to Archives.org, I have extracted his commentary on Verdun.

In November and December, 1915, our successes against Serbia

and Montenegro had brought on the fourth Isonzo battle, and,

about Christmas, the Russian offensive on the southern portion

of the Austro-Hungarian front. This attack lasted into January

of 1916. Both concluded in a successful resistance on the part

of our Allies.

The two General Staffs had now to make their plans for the campaign of 1916. Both were to attempt an offensive to bring about a decision. The German G.H.Q. proposed to attack at Verdun, while the Austro-Hungarian had in view an offensive against Italy from the Tyrol. To make the offensive against Verdun possible, heavy artillery had to be transferred from the German East Front to the West. I do not know what the Entente had in view for 1916 before the French Army was compelled to concentrate on Verdun. It appeared, and indeed it was only to be expected, that they were contemplating great offensives on all fronts.

Strategically Verdun as the point of attack was well chosen This fortress had always served as a particularly dangerous sally- port, which very seriously threatened our communications, as the autumn of 1918 disastrously proved. Had we only been able to reach the defenses on the right bank of the Meuse, we should have achieved complete success. Our strategic position on the Western Front, as well as the tactical situation of our troops in the St. Mihiel salient, would have been materially improved. The attack began on February 21st and met with great success, especially during the early days, owing to the brilliant qualities of our men. The advantage, however, was insufficiently exploited, and our advance soon came to a standstill. At the beginning of March the world was still under the impression that the Germans had won a victory at Verdun.

The German attack at Verdun led to no decisive result. By May it bore the stamp of the first great battle of attrition, in which the struggle for victory means feeding the fighting line with a continuous mass of men and materials. The other parts of the Western Front were inactive.

On the Western Front the Verdun battle was dying down, and in the early days of July the battle on the Somme had not brought the Entente the break-through they hoped for.

The second battle of attrition of the year 1916 had since then been in full swing on both banks of the Somme, and was raging with unprecedented fury and without a moment’s respite.

Verdun had exacted a very great price in blood. The position

of our attacking troops grew more and more unfavorable. The

more ground they gained the deeper they plunged into the

wilderness of shell-holes, and apart from actual losses in action,

they suffered heavy wastage merely through having to stay in such

a spot, not to mention the difficulty of getting up supplies over

a wide, desolate area. The French enjoyed a great advantage

here, as the proximity of the fortress gave them a certain amount

of support. Our attacks dragged on, sapping our strength.

The very men who had fought so heroically at Verdun were terrified

of this shell-ravaged region. The Command had not their

hearts in their work. The Crown Prince had very early declared

himself in favor of breaking off the attack.

The Field-Marshal [Hindenburg] and I intended, as soon as conditions allowed, to go to the Western Front to see for ourselves how matters really stood there. Our task was to organize a stiffer defense and advise generally. But before we went there, some divisions were got ready for Romania and H.M. the Emperor was induced to give the momentous order for the cessation of the offensive at Verdun. That offensive should have been broken off immediately it assumed the character of a battle of attrition. The gain no longer justified the losses. On the defensive we had only to hold out in a battle of attrition forced upon us.

The Crown Prince was greatly pleased at the abandonment of the attacks on Verdun, a course he had long and earnestly desired. He discussed other matters also, and mentioned to me his desire for peace ; he did not explain how this was to be obtained from the Entente.

The most pressing demands of our officers [at the Somme] were for an increase of artillery, ammunition, aircraft and balloons, as well as larger and more punctual allotments of fresh divisions and other troops to make possible a better system of reliefs. The breaking-off of the attack on Verdun made it easier to satisfy their wishes; but even there we had to reckon in the future with considerable wastage, if only on account of the local conditions. It was possible that the French would themselves make an attack from the fortress. Verdun remained an open, wasting sore.

At that time I had not a thorough grasp of the local difficulties of the Verdun fighting. After the Somme, the fortress still required the most attention, in spite of that the 5th Army would have to surrender a considerable amount of artillery and aircraft.

In October. . . The struggle continued in the shell-hole area on the north-

eastern front of Verdun. The French were pushing forward

and we remained on the defensive. The troops were very exhausted. But there was no change in the general situation

there.

As fighting on the French sector of the Somme battlefield died down, the position before Verdun again became critical. The French attacked on the 24th; we lost Fort Douaumont, and on the 1st of November were obliged to evacuate Fort Vaux also. The loss was grievous, but still more grievous was the totally unexpected decimation of some of our divisions.

On the 14th, 15th and 16th of December, however, there was again very hard fighting round Verdun. France attacked so as to limit still further, before the end of the year, the German gains of 1916 before this fortress. They achieved their object. The blow they dealt us was particularly heavy. We not only suffered heavy casualties, but also lost important positions. The strain during this year had proved too great. The endurance of the troops had been weakened by long spells of defense under the powerful enemy artillery fire and their own losses. We were completely exhausted on the Western Front. . . The enemy, too, seemed weary. But they still had the strength to deliver their so successful blow near Verdun.

|

| General Ludendorff |

The two General Staffs had now to make their plans for the campaign of 1916. Both were to attempt an offensive to bring about a decision. The German G.H.Q. proposed to attack at Verdun, while the Austro-Hungarian had in view an offensive against Italy from the Tyrol. To make the offensive against Verdun possible, heavy artillery had to be transferred from the German East Front to the West. I do not know what the Entente had in view for 1916 before the French Army was compelled to concentrate on Verdun. It appeared, and indeed it was only to be expected, that they were contemplating great offensives on all fronts.

Strategically Verdun as the point of attack was well chosen This fortress had always served as a particularly dangerous sally- port, which very seriously threatened our communications, as the autumn of 1918 disastrously proved. Had we only been able to reach the defenses on the right bank of the Meuse, we should have achieved complete success. Our strategic position on the Western Front, as well as the tactical situation of our troops in the St. Mihiel salient, would have been materially improved. The attack began on February 21st and met with great success, especially during the early days, owing to the brilliant qualities of our men. The advantage, however, was insufficiently exploited, and our advance soon came to a standstill. At the beginning of March the world was still under the impression that the Germans had won a victory at Verdun.

The German attack at Verdun led to no decisive result. By May it bore the stamp of the first great battle of attrition, in which the struggle for victory means feeding the fighting line with a continuous mass of men and materials. The other parts of the Western Front were inactive.

On the Western Front the Verdun battle was dying down, and in the early days of July the battle on the Somme had not brought the Entente the break-through they hoped for.

The second battle of attrition of the year 1916 had since then been in full swing on both banks of the Somme, and was raging with unprecedented fury and without a moment’s respite.

|

| German Assault on Mort Homme |

The Field-Marshal [Hindenburg] and I intended, as soon as conditions allowed, to go to the Western Front to see for ourselves how matters really stood there. Our task was to organize a stiffer defense and advise generally. But before we went there, some divisions were got ready for Romania and H.M. the Emperor was induced to give the momentous order for the cessation of the offensive at Verdun. That offensive should have been broken off immediately it assumed the character of a battle of attrition. The gain no longer justified the losses. On the defensive we had only to hold out in a battle of attrition forced upon us.

The Crown Prince was greatly pleased at the abandonment of the attacks on Verdun, a course he had long and earnestly desired. He discussed other matters also, and mentioned to me his desire for peace ; he did not explain how this was to be obtained from the Entente.

The most pressing demands of our officers [at the Somme] were for an increase of artillery, ammunition, aircraft and balloons, as well as larger and more punctual allotments of fresh divisions and other troops to make possible a better system of reliefs. The breaking-off of the attack on Verdun made it easier to satisfy their wishes; but even there we had to reckon in the future with considerable wastage, if only on account of the local conditions. It was possible that the French would themselves make an attack from the fortress. Verdun remained an open, wasting sore.

At that time I had not a thorough grasp of the local difficulties of the Verdun fighting. After the Somme, the fortress still required the most attention, in spite of that the 5th Army would have to surrender a considerable amount of artillery and aircraft.

|

| German Defenders Late in the Battle |

As fighting on the French sector of the Somme battlefield died down, the position before Verdun again became critical. The French attacked on the 24th; we lost Fort Douaumont, and on the 1st of November were obliged to evacuate Fort Vaux also. The loss was grievous, but still more grievous was the totally unexpected decimation of some of our divisions.

On the 14th, 15th and 16th of December, however, there was again very hard fighting round Verdun. France attacked so as to limit still further, before the end of the year, the German gains of 1916 before this fortress. They achieved their object. The blow they dealt us was particularly heavy. We not only suffered heavy casualties, but also lost important positions. The strain during this year had proved too great. The endurance of the troops had been weakened by long spells of defense under the powerful enemy artillery fire and their own losses. We were completely exhausted on the Western Front. . . The enemy, too, seemed weary. But they still had the strength to deliver their so successful blow near Verdun.

Saturday, September 21, 2019

Henry A. Wise Wood’s War and Peace

|

| Henry A. Wise Wood |

The name Henry A. Wise Wood may not ring familiar, but this inventor, businessman, writer, and activist was instrumental in the debate—and ultimate defeat—of American entry into the Covenant of the League of Nations. He made his fortune as president and chairman of the Wood Newspaper Machinery Corporation. In a sense he literally helped accelerate the rise of the penny press: his numerous advancements, including the Autoplate, allowed newspapers to come off the line at a rate of 60,000 per hour, more the twice the rate of 24,000 per hour it had been previously. He also had a keen interest in both aeronautics and submarines and was one of the first to understand how transportation and communications technology would come together in 20th-century warfare. Wood was the first president of the American Society of Aeronautical Engineers. He was a member of the Aero Club of America and in 1911 founded and edited Flying, a magazine dedicated to that nascent field. He was also a published poet.

Given this background and history, then, it is not surprising that Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels invited Wood to join the United States Naval Consulting Board, a civilian advisory body Daniels created in September 1915 whose purpose was to evaluate the efficacy of the numerous technological ideas pitched by a concerned public to the Navy Department now that war had come to Europe. Thomas Edison served as president of the Naval Consulting Board, which was comprised of the country’s leading inventors, scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and business figures. Wood resigned by year’s end in frustration over what he believed was the Wilson administration’s unwillingness to ready Americans for war. Henry A. Wise Wood was not the first in his family to publicly disagree with a presidential administration about how best to handle armed conflict. His father was Fernando Wood, the New York City mayor (and later congressman) who half a century earlier had tangled with President Lincoln during the American Civil War. Henry was born in March 1866, less than a year after Appomattox.

After his disillusionment with the Consulting Board experience, Wood joined Theodore Roosevelt and others in the Preparedness Movement, soon becoming chairman of the Conference Committee on National Preparedness. He left the Democratic Party and supported Charles Evans Hughes against Wilson in 1916. Wood noisily criticized the Wilson administration even after the America joined the fight the following year. When the Armistice came he was naturally anxious to see what the peace might look like. Wood began his opposition to Wilson’s proposal as early as February 1919, though he refrained from criticizing Wilson publicly while the president was in Europe. Theodore Roosevelt was gone by this time, but Wood and others carried on the fight in his spirit. By early March 1919 he and his associates formed a group called the League for the Preservation of American Independence with a kick-off at the Hotel Pennsylvania. Numerous senators, including Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and Warren G. Harding, sent messages of support. They opened an office at 1 Madison Avenue and Independence League branches quickly opened in other cities across the country.

Henry A. Wise Wood let his opinions about the League of Nations be known through numerous speeches and letters to editor, including via vehicles as the New York Times, whose presses ran on machines designed largely by Wood himself. Wood even pushed for Wilson’s impeachment. He also debated League of Nations supporters in public venues, including a face-off with New Jersey politician and businessman Everett Colby in East Orange in April 1919. On 28 June Wood’s League for the Preservation of American Independence organized a sold-out event at Carnegie Hall featuring senators James A. Reed (D-MO) and Hiram Johnson (R-CA), the latter previously a founder of the Progressive Party and 1912 running mate of Roosevelt’s on the national Bull Moose ticket. Hundreds stood on the sidewalk outside, unable to get in but eager to make their opinions known through their presence. Hiram Warren Johnson in particular was never one to hold his feelings back either publicly or in private. Writing in a letter to his children on 31 May 1919, the California senator had declared that “I firmly believe [the League of Nations] to be the most iniquitous thing presented at least during my lifetime.” He electrified the Carnegie Hall crowd.

|

| Senator Hiram Johnson |

Debate over American entry into the League of Nations continued all summer. In late August Wood and other members of the Independence League wrote an open letter to all U.S. senators laying out their concerns. On 25 September 1919 Wood telegraphed Wilson, who was then in Wichita, Kansas, exhausting himself on his whistle-stop tour in promotion of the League of Nations. Wood averred to Wilson in that missive that opposition to the the League of Nations, contrary to Wilson’s public utterances, extended beyond just various congressman and “hyphenated Americans,” a term for naturalized and first generation ethnic citizens. Wood’s telegram came at a stressful time for the president. The grind of this tour—Wilson covered more than 8,000 miles in just over three weeks—contributed to the debilitating stroke he suffered on 2 October.

Still, even with the president incapacitated the debate raged on. Senator Johnson spoke to several hundred at a luncheon sponsored by the Los Angeles branch of the League for the Preservation of American Independence in that city on 3 October, the day after Wilson’s stroke. Johnson’s talk was held in the same hotel ballroom where Woodrow Wilson had spoken in favor Senate ratification just two weeks previously. Later that very night Senator Johnson spoke to an audience of 7,000 persons further explaining his disapproval with the Versailles Treaty. A culmination of sorts came on 18 October 1919 when a crowd of 10,000 attended a League for the Preservation of American Independence rally at New York City’s Madison Square Garden, then on 26th Street and Madison Avenue. The United States Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles the following month on 19 November. Wilson’s beloved treaty was not entirely dead; the debate would go in for some time. The momentum however had turned inexorably against the president.

Wood remained part of that argument and then went on to other pursuits in the 1920s, including continuing with his profitable newspaper machinery business, scientific and technological interests, and reactionary advocacy for such causes as immigration restriction. He lived long enough to see the rise of Hitler and such events as the annexation of Austria in March 1938 and invasion of Czechoslovakia twelve months later. The second global war that Wood and others had predicted two decades previously was at hand. Henry A. Wise Wood died at his home on Fifth Avenue adjacent to Central Park on 9 April 1939 and is buried today at Mount Adnah Cemetery in Annisquam, Massachusetts.

Keith Muchowski, a librarian and professor at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) in Brooklyn, writes occasionally for Roads to the Great War. [This is Keith's 14th article for us. MH] He recently finished a manuscript about Civil War era New York City.

Keith blogs at thestrawfoot.com.

Friday, September 20, 2019

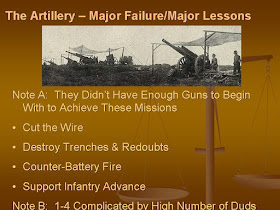

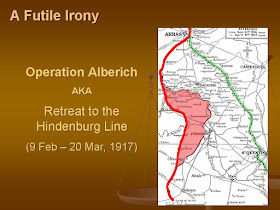

My Battle of the Somme Slide Show, Part II

On the Centennial of the Battle of the Somme, I presented a program on the struggle to the World War One Historical Association. Over the past two days, I'm presenting a selection of the slides I used in that program, mainly to give a feel for the battle and its importance historically. We have presented dozens of articles on the Battle of the Somme on Roads to the Great War. If you would like more detailed information on it, just enter "Somme" in the search box at the top of the page.

Click on Image to Enlarge Slide

Check Yesterday's Post for Part I

Thursday, September 19, 2019

My Battle of the Somme Slide Show, Part I

On the Centennial of the Battle of the Somme, I presented a program on the struggle to the World War One Historical Association. Over the next two days, I'm going to present a selection of the slides, mainly to give a feel for the battle and its importance historically. We have presented dozens of articles on the Battle of the Somme on Roads to the Great War. If you would like more detailed information on it, just enter "Somme" in the search box at the top of the page.

Click on Images to Enlarge Slides

Part II Tomorrow

Wednesday, September 18, 2019

The U.S. Coast Guard's Service in the Great War

HOMELAND DEFENSE

The outbreak of World War I (WWI) in 1914 saw cutters become responsible for enforcing U.S. neutrality laws. Soon after, in January 1915, these cutters and their

officers and crews merged with the U.S. Life-Saving Service to become the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard was specifically created as an armed service of the U.S. and

was directed to transfer to the Navy in the event of war or upon direction by the president. Plans were immediately put into place to work carefully with the Navy in

determining what roles the Coast Guard might play in any future conflict. Those plans were implemented quickly with the U.S. declaration of war against Germany on

6 April 1917. At that time, a coded dispatch was transmitted from Washington, D.C., via the Navy radio station in Alexandria, VA, to every Coast Guard cutter and

shore station. Officers, enlisted men, vessels, and units were transferred to the operational control of the Department of the Navy. The Coast Guard augmented the Navy

with its 223 commissioned officers, more than 4,500 enlisted men, 47 vessels of all types, and 279 stations scattered along the entire U.S. coastline.

The outbreak of World War I (WWI) in 1914 saw cutters become responsible for enforcing U.S. neutrality laws. Soon after, in January 1915, these cutters and their

officers and crews merged with the U.S. Life-Saving Service to become the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard was specifically created as an armed service of the U.S. and

was directed to transfer to the Navy in the event of war or upon direction by the president. Plans were immediately put into place to work carefully with the Navy in

determining what roles the Coast Guard might play in any future conflict. Those plans were implemented quickly with the U.S. declaration of war against Germany on

6 April 1917. At that time, a coded dispatch was transmitted from Washington, D.C., via the Navy radio station in Alexandria, VA, to every Coast Guard cutter and

shore station. Officers, enlisted men, vessels, and units were transferred to the operational control of the Department of the Navy. The Coast Guard augmented the Navy

with its 223 commissioned officers, more than 4,500 enlisted men, 47 vessels of all types, and 279 stations scattered along the entire U.S. coastline.

During WWI, the Coast Guard continued to enforce rules and regulations that

governed the anchorage and movements of vessels in American harbors. The

Espionage Act, passed in June 1917, gave the Coast Guard further power to protect

merchant shipping from sabotage. This act included the safeguarding of waterfront

property, supervision of vessel movements, establishment of anchorages and

restricted areas, and the right to control and remove people aboard ships. The

tremendous increase in munitions shipments,

particularly in New York, required an increase

in personnel to oversee this activity. The term

“captain of the port” (COTP) was first used in

New York, and Captain Godfrey L. Carden was

the first to hold that title. As COTP, he was

charged with supervising the safe loading of

explosives. During the war, a similar post was

established in other U.S. ports. However, the

majority of the nation’s munitions shipments abroad left through New York. For a

period of one-and-a-half years, more than 1,600 vessels, carrying more than 345 million tons

of explosives, sailed from this port. In 1918, Carden’s division was the largest single

command in the Coast Guard. It consisted of more than 1,400 officers and men, four

Corps of Engineers tugboats, and five harbor cutters.

OVERSEAS COMBAT

In August and September 1917, six U.S. Coast Guard Cutters (USCGC), Ossipee,

Seneca, Yamacraw, Algonquin, Manning, and Tampa, left the United States to join

U.S. naval forces in European waters. They constituted Squadron 2 of Division 6 of

the patrol forces of the Atlantic Fleet and were based in Gibraltar. Throughout the war

they escorted hundreds of vessels between Gibraltar and the British Isles. The other

large cutters performed similar duties in home waters, off Bermuda, in the Azores, in

the Caribbean, and off the coast of Nova Scotia. They

operated either under the orders of the commandants

of the various naval districts or under the direct orders

of the Chief of Naval Operations. One cutter, Tampa,

was lost in combat with all 115 crew and 15 passengers

aboard, a dreadful loss for such a small service.

NAVAL COMMAND

A large number of Coast Guard officers held important commands during WWI. Twenty-four commanded naval warships in the war zone, five commanded warships attached to the American Patrol detachment in the Caribbean Sea, twenty-three commanded warships attached to naval districts, and five Coast Guard officers commanded large training camps. Six were assigned to aviation duty, two of whom commanded important air stations including one in France. Shortly after the Armistice, four Coast Guard officers were assigned to command large naval transports engaged in bringing the troops home from France. Officers not assigned to command served in practically every phase of naval activity: on transports, cruisers, cutters, patrol vessels, in naval districts, as inspectors, and at training camps. Of the 223 commissioned officers of the Coast Guard, seven met their deaths as a result of enemy action.

LOSSES & AWARDS

Besides those lost aboard USCGC Tampa, eleven were lost from USCGC Seneca on a combat search-and-rescue mission, and another 70 lost their lives due to accident or illness. Two cutters were lost due to collisions, USCGC McCulloch off San Francisco and USCGC Mohawk off Sandy Hook. Heroism was common among Coast Guardsmen as they were awarded two Distinguished Service Medals, eight Gold Life-Saving Medals, 49 Navy Crosses, and 11 foreign awards.

BACK TO PEACETIME

U.S. Coast Guard Chief Historian Scott Price described what happened to the service after the Armistice. "The biggest challenge was to get the Coast Guard back under the Treasury Department—many of the Coast Guard officers liked serving with the Navy, since there were better chances at promotion, etc. so that was one hurdle that had to be surmounted. And before they had a chance to really incorporate the lessons they learned during the war, the nation undertook the great experiment that was Prohibition and so once again we were thrust into a huge new task, one unlike anything we had done to that time, and that consumed the Coast Guard for the next decade or so. But lessons were learned and by the time World War II came around, our escort-of-convoy and port security duties were still paramount—as well as our coastal defense responsibilities."

Sources: United States Coast Guard and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

The outbreak of World War I (WWI) in 1914 saw cutters become responsible for enforcing U.S. neutrality laws. Soon after, in January 1915, these cutters and their

officers and crews merged with the U.S. Life-Saving Service to become the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard was specifically created as an armed service of the U.S. and

was directed to transfer to the Navy in the event of war or upon direction by the president. Plans were immediately put into place to work carefully with the Navy in

determining what roles the Coast Guard might play in any future conflict. Those plans were implemented quickly with the U.S. declaration of war against Germany on

6 April 1917. At that time, a coded dispatch was transmitted from Washington, D.C., via the Navy radio station in Alexandria, VA, to every Coast Guard cutter and

shore station. Officers, enlisted men, vessels, and units were transferred to the operational control of the Department of the Navy. The Coast Guard augmented the Navy

with its 223 commissioned officers, more than 4,500 enlisted men, 47 vessels of all types, and 279 stations scattered along the entire U.S. coastline.

The outbreak of World War I (WWI) in 1914 saw cutters become responsible for enforcing U.S. neutrality laws. Soon after, in January 1915, these cutters and their

officers and crews merged with the U.S. Life-Saving Service to become the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard was specifically created as an armed service of the U.S. and

was directed to transfer to the Navy in the event of war or upon direction by the president. Plans were immediately put into place to work carefully with the Navy in

determining what roles the Coast Guard might play in any future conflict. Those plans were implemented quickly with the U.S. declaration of war against Germany on

6 April 1917. At that time, a coded dispatch was transmitted from Washington, D.C., via the Navy radio station in Alexandria, VA, to every Coast Guard cutter and

shore station. Officers, enlisted men, vessels, and units were transferred to the operational control of the Department of the Navy. The Coast Guard augmented the Navy

with its 223 commissioned officers, more than 4,500 enlisted men, 47 vessels of all types, and 279 stations scattered along the entire U.S. coastline.

|

| Men of the Port of New York Detachment Drilling |

OVERSEAS COMBAT

|

| Cutter Yamacraw Was Assigned to Convoy Duty |

|

| The Crew of the USS Tampa — All Were Lost at Sea, 26 Sept. 1918 (Major Roads Article) |

A large number of Coast Guard officers held important commands during WWI. Twenty-four commanded naval warships in the war zone, five commanded warships attached to the American Patrol detachment in the Caribbean Sea, twenty-three commanded warships attached to naval districts, and five Coast Guard officers commanded large training camps. Six were assigned to aviation duty, two of whom commanded important air stations including one in France. Shortly after the Armistice, four Coast Guard officers were assigned to command large naval transports engaged in bringing the troops home from France. Officers not assigned to command served in practically every phase of naval activity: on transports, cruisers, cutters, patrol vessels, in naval districts, as inspectors, and at training camps. Of the 223 commissioned officers of the Coast Guard, seven met their deaths as a result of enemy action.

LOSSES & AWARDS

Besides those lost aboard USCGC Tampa, eleven were lost from USCGC Seneca on a combat search-and-rescue mission, and another 70 lost their lives due to accident or illness. Two cutters were lost due to collisions, USCGC McCulloch off San Francisco and USCGC Mohawk off Sandy Hook. Heroism was common among Coast Guardsmen as they were awarded two Distinguished Service Medals, eight Gold Life-Saving Medals, 49 Navy Crosses, and 11 foreign awards.

|

| USCGC McCulloch Sinking Off of San Francisco |

BACK TO PEACETIME

U.S. Coast Guard Chief Historian Scott Price described what happened to the service after the Armistice. "The biggest challenge was to get the Coast Guard back under the Treasury Department—many of the Coast Guard officers liked serving with the Navy, since there were better chances at promotion, etc. so that was one hurdle that had to be surmounted. And before they had a chance to really incorporate the lessons they learned during the war, the nation undertook the great experiment that was Prohibition and so once again we were thrust into a huge new task, one unlike anything we had done to that time, and that consumed the Coast Guard for the next decade or so. But lessons were learned and by the time World War II came around, our escort-of-convoy and port security duties were still paramount—as well as our coastal defense responsibilities."

Sources: United States Coast Guard and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security