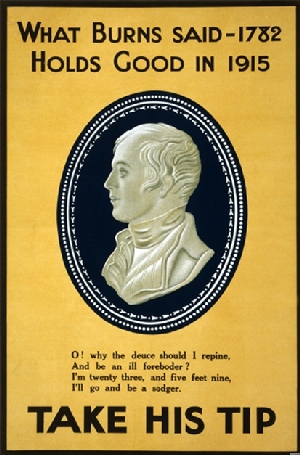

With Scotland's sons deeply involved in the war, the memory of Robert Burns was drawn upon for recruitment and inspiration. In 1787, Robert Burns had written the Address to the Haggis in celebration of Scotland’s national dish. It is traditionally recited before eating the Haggis on the occasion of Burns's birthday. Scots-Canadian Robert Service, who drove an ambulance on the Western Front, contributed his own poem on the occasion of Burns's birthday that combines the trench experience with the eating of the Haggis.

The Haggis of Private McPhee

Robert Service

"Hae ye heard whit ma auld mither's postit tae me?

It fair maks me hamesick," says Private McPhee.

"And whit did she send ye?" says Private McPhun,

As he cockit his rifle and bleezed at a Hun.

"A haggis! A Haggis!" says Private McPhee;

"The brawest big haggis I ever did see.

And think! it's the morn when fond memory turns

Tae haggis and whuskey--the Birthday o' Burns.

We maun find a dram; then we'll ca' in the rest

O' the lads, and we'll hae a Burns' Nicht wi' the best."

"Be ready at sundoon," snapped Sergeant McCole;

"I want you two men for the List'nin' Patrol."

Then Private McPhee looked at Private McPhun:

"I'm thinkin', ma lad, we're confoundedly done."

Then Private McPhun looked at Private McPhee:

"I'm thinkin' auld chap, it's a' aff wi' oor spree."

But up spoke their crony, wee Wullie McNair:

"Jist lea' yer braw haggis for me tae prepare;

And as for the dram, if I search the camp roun',

We maun hae a drappie tae jist haud it doon.

Sae rin, lads, and think, though the nicht it be black,

O' the haggis that's waitin' ye when ye get back."

(2)

My! but it wis waesome on Naebuddy's Land,

And the deid they were rottin' on every hand.

And the rockets like corpse candles hauntit the sky,

And the winds o' destruction went shudderin' by.

There wis skelpin' o' bullets and skirlin' o' shells,

And breengin' o' bombs and a thoosand death-knells;

But cooryin' doon in a Jack Johnson hole

Little fashed the twa men o' the List'nin' Patrol.

For sweeter than honey and bricht as a gem

Wis the thocht o' the haggis that waitit for them.

Yet alas! in oor moments o' sunniest cheer

Calamity's aften maist cruelly near.

And while the twa talked o' their puddin' divine

The Boches below them were howkin' a mine.

And while the twa cracked o' the feast they would hae,

The fuse it wis burnin' and burnin' away.

Then sudden a roar like the thunner o' doom,

A hell-leap o' flame . . . then the wheesht o' the tomb.

"Haw, Jock! Are ye hurtit?" says Private McPhun.

"Ay, Geordie, they've got me; I'm fearin' I'm done.

It's ma leg; I'm jist thinkin' it's aff at the knee;

Ye'd best gang and leave me," says Private McPhee.

"Oh leave ye I wunna," says Private McPhun;

"And leave ye I canna, for though I micht run,

It's no faur I wud gang, it's no muckle I'd see:

I'm blindit, and that's whit's the maitter wi' me."

Then Private McPhee sadly shakit his heid:

"If we bide here for lang, we'll be bidin' for deid.

And yet, Geordie lad, I could gang weel content

If I'd tasted that haggis ma auld mither sent."

"That's droll," says McPhun; "ye've jist speakit

ma mind.

Oh I ken it's a terrible thing tae be blind;

And yet it's no that that embitters ma lot--

It's missin' that braw muckle haggis ye've got."

For a while they were silent; then up once again

Spoke Private McPhee, though he whussilt wi' pain:

"And why should we miss it? Between you and me

We've legs for tae run, and we've eyes for tae see.

You lend me your shanks and I'll lend you ma sicht,

And we'll baith hae a kyte-fu' o' haggis the nicht."

Oh the sky it wis dourlike and dreepin' a wee,

When Private McPhun gruppit Private McPhee.

Oh the glaur it wis fylin' and crieshin' the grun',

When Private McPhee guidit Private McPhun.

"Keep clear o' them corpses--they're maybe no deid!

Haud on! There's a big muckle crater aheid.

Look oot! There's a sap; we'll be haein' a coup.

A staur-shell! For Godsake! Doun, lad, on yer daup.

Bear aff tae yer richt. . . . Aw yer jist daein' fine:

Before the nicht's feenished on haggis we'll dine."

(3)

There wis death and destruction on every hand;

There wis havoc and horror on Naebuddy's Land.

And the shells bickered doun wi' a crump and a glare,

And the hameless wee bullets were dingin' the air.

Yet on they went staggerin', cooryin' doun

When the stutter and cluck o' a Maxim crept roun'.

And the legs o' McPhun they were sturdy and stoot,

And McPhee on his back kept a bonnie look-oot.

"On, on, ma brave lad! We're no faur frae the goal;

I can hear the braw sweerin' o' Sergeant McCole."

But strength has its leemit, and Private McPhun,

Wi' a sab and a curse fell his length on the grun'.

Then Private McPhee shoutit doon in his ear:

"Jist think o' the haggis! I smell it from here.

It's gushin' wi' juice, it's embaumin' the air;

It's steamin' for us, and we're--jist--aboot--there."

Then Private McPhun answers: "Dommit, auld chap!

For the sake o' that haggis I'll gang till I drap."

And he gets on his feet wi' a heave and a strain,

And onward he staggers in passion and pain.

And the flare and the glare and the fury increase,

Till you'd think they'd jist taken a' hell on a lease.

And on they go reelin' in peetifu' plight,

And someone is shoutin' away on their right;

And someone is runnin', and noo they can hear

A sound like a prayer and a sound like a cheer;

And swift through the crash and the flash and the din,

The lads o' the Hielands are bringin' them in.

"They're baith sairly woundit, but is it no droll

Hoo they rave aboot haggis?" says Sergeant McCole.

When hirplin alang comes wee Wullie McNair,

And they a' wonnert why he wis greetin' sae sair.

And he says: "I'd jist liftit it oot o' the pot,

And there it lay steamin' and savoury hot,

When sudden I dooked at the fleech o' a shell,

And it--dropped on the haggis and dinged it tae hell."

And oh but the lads were fair taken aback;

Then sudden the order wis passed tae attack,

And up from the trenches like lions they leapt,

And on through the nicht like a torrent they swept.

On, on, wi' their bayonets thirstin' before!

On, on tae the foe wi' a rush and a roar!

And wild to the welkin their battle-cry rang,

And doon on the Boches like tigers they sprang:

And there wisna a man but had death in his ee,

For he thocht o' the haggis o' Private McPhee.