Click on Image to Enlarge

Now all roads lead to France and heavy is the treadEdward Thomas, Roads

Of the living; but the dead returning lightly dance.

Saturday, September 30, 2023

The Few but Dramatic WWI Posters of Dan Smith

Friday, September 29, 2023

A World War I Marine Gave Us the "Bazooka"

|

| Marine Bob Burns with His Bazooka |

By Todd Smith

(Originally published in the "Observation Post" of The Marine Corps Times, 3 September 2021)

Arkansas native Bob Burns enlisted in the Marine Corps during World War I and sailed to France in 1918 as part of the 11th Regiment. The artillery detachment converted quickly to infantry for trench fighting but saw little action, allowing time for Sgt. Burns, the lead in the Marine Corps’ jazz band, to fashion a homemade instrument that would become a part of combat lore for decades to come.

Back in the States the following year, a newspaper article noted that Burns’ deft jazz playing was drawing in young men to a Marine Corps recruiting office in New York City, according to Sept 1919 edition of the New York Evening Telegram.

“We play everything from Berlin (Irving) to Mr. Beethoven and will tackle anything except a funeral march,” said Robbie (Bob) Burns. “The outfit consists of two violins, a banjo, piano, drum, and the bazooka.”

Bazooka. The word traces its origins back to “bazoo,” a slang term for mouth that, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, may have come from the Dutch term for trumpet, bazuin.

“According to tales told by the Marines, the Melody Six are the snappiest, zippiest, jazziest aggregation of tune artists in any branch of Uncle Sam’s service,” the newspaper article noted in a section adjacent to Burns’ own instructions to building that very item: “Two pieces of gas pipe, one tin funnel, a little axle grease and a lot of perseverance.”

Around that same time, a little-known project was getting underway to help infantry soldiers and Marines battle the devastating effects of the recently fielded tank.

Dr. Robert Goddard, a scientist developing weapons for the Army, who invented the first liquid-fueled rocket, had set his sights on building a tube-fired weapon capable of being carried by a single soldier. But as the war came to its conclusion, the project was shelved.

Decades later, with the U.S. blazing its trail against German forces in North Africa, military planners were again trying to find a way for foot soldiers to take on the tank, a weapon that had vastly improved in the decades since. Rifle grenade launchers, after all, did little to disable German tracks.

Revisiting Goddard’s plans fell to Army Col. Leslie Skinner, who had sketched out designs for such a weapon in 1940. It wasn’t long before the M10 shaped charge came into the arsenal, stirring the ashes of the abandoned project.

“I was walking by this scrap pile, and there was a tube that ... happened to be the same size as the grenade that we were turning into a rocket,” read a Time magazine quote from Lt. Edward Uhl, who Skinner tasked to introduce a little innovation to the project. “I said ‘That’s the answer!’ Put the tube on a soldier’s shoulder with the rocket inside, and away it goes.”

By May 1942, testing at the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Grounds had commenced. The warhead was matched with the tube, while testers employed a wire coat hanger as improvised sights prior to unleashing it on a moving tank.

One observer of the new weapon noted that the new launcher “looks like Bob Burns’ bazooka.” Thus, a funky name was married to an even funkier weapon. The M1 “Bazooka” was produced and fielded during the North Africa campaign’s Operation Torch in October 1942. Soldiers loved it. (I still do.)

|

| Marine Bazooka Squad During the Korean War |

After seeing it in action and capturing a few, the Nazis quickly reverse-engineered it to produce the Panzerschreck, or “tank scare,” meaner-sounding than the bazooka, but then again most German words are.

By the end of World War II, the Japanese military also had produced their own version.

Additional models made by the U.S. military would march on through at least seven more variations, from the original, a 60mm warhead that could penetrate 3 inches of armor, to the Super Bazooka, a Korean War weapon that launched an 88.9mm warhead and could tear through 11 inches of armor.

The Super Bazooka even saw service in Vietnam before being replaced by improved shoulder-fired rockets.

With time, the “bazooka” name fizzled from the vernacular of shoulder-fired weaponry, officially ending with the “Three Shot Bazooka,” a tripod-mounted variant with an overhead magazine that fired, you guessed it, three rounds. Still, today’s Marine and Army-issued Carl Gustaf 84mm recoilless rifles traces roots back to the scrap pile and rural ingenuity of an Arkansas-born Marine.

|

| Show Biz Bob Burns with His Bazooka |

As for Bob Burns, he segued his jazz skills into a career as a musician, comedian, and film actor in early Hollywood. Burns made appearances in more than two dozen films and for a time manned his own radio program, The Bob Burns Show. Burns died in 1956 at the age of 65. Needless to say, his life was a blast.

Thursday, September 28, 2023

Command and Cultural Issues Underlying the British Surrender at Kut-al-Amara

|

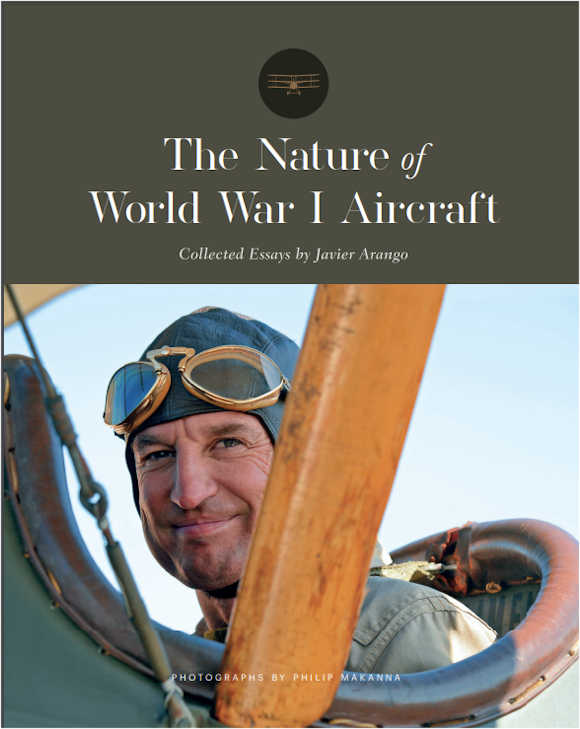

| General Townshend in Custody After the Surrender |

An Excerpt from Armies in Retreat: Chaos, Cohesion, and Consequences, Chapter 3, "Clausewitzian Friction and the Retreat of 6 Indian Division to Kut-al-Amara, November–December 1915 by Nikolas E. Gardner

Overview

In September 1915, Major-General Charles Townshend’s 6 Indian Division, the vanguard of Indian Expeditionary Force D (IEFD), began advancing up the Tigris River with the intent of reaching Baghdad. From 22 to 25 November, however, the division engaged superior Ottoman forces at Ctesiphon, less than 30 miles from its objective. After sustaining heavy casualties, Townshend’s force withdrew from the battlefield on the evening of 25 November. Eight days later, after retreating more than 90 miles downriver with the enemy in pursuit, 6 Indian Division reached the town of Kut-al-Amara, where Townshend halted. Ottoman forces subsequently surrounded the town and established defensive positions farther down the Tigris. Despite multiple unsuccessful attempts by British forces to break through these positions, disease and starvation forced the division to surrender in late April 1916.

. . . Influenced by Townshend’s memoir of the campaign, scholars have assumed that the British commander resolved to seek refuge at Kut-al-Amara during the engagement at Ctesiphon or shortly afterward. If this was the case, then the siege appears to have been a foregone conclusion. Yet a careful assessment of 6 Indian Division’s retreat from Ctesiphon demonstrates that Townshend’s decision to halt at Kut was not preordained. In fact, it was a result of mounting fatigue, ongoing uncertainty about the location of enemy forces, and increasing concern about the morale of Townshend’s own subordinates.

Townshend's Army

|

| Men of the 6 Poona Division with British Officer, Mesopotamia |

To understand Charles Townshend’s decisions during the retreat, it is helpful to become acquainted with the 6 Indian Division commander and the force he led. Fifty-four years old in 1915, Townshend had built his career in British colonial campaigns in India and Africa. He first gained renown as a captain when he led the successful British defense of the Chitral fort in India’s North West Frontier region against a siege by local forces in 1895. Three years later, he commanded an African regiment during the successful British campaign in Sudan. Townshend’s career progressed steadily during the first decade of the twentieth century. By 1911, he had attained the rank of major-general. Townshend proved restless, however, continually lobbying for new opportunities in Britain and India in an effort to gain promotion and acclaim. The outbreak of the First World War appeared to be just such an opportunity. But as commander of the Rawal Pindi Brigade in August 1914, Townshend watched with frustration as other Indian formations embarked on operations to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East while he remained on garrison duty. Thus, when Lieutenant-General Sir John Nixon, the IEFD commander in Mesopotamia, offered him command of 6 Indian Division in the spring of 1915, Townshend seized the opportunity.

Despite Townshend’s extensive imperial service, however, he had little experience commanding the Indian personnel who composed the majority of the division. Each of 6 Indian Division’s three infantry brigades included three battalions of Indian sepoys alongside a single British battalion. Attached to the division was an additional infantry brigade of similar composition, as well as a cavalry brigade comprising three regiments of Indian mounted troops (referred to as sowars), three companies of Indian sappers and miners, six British artillery batteries, and an additional battery of “mixed race” Eurasian personnel. Accompanying the division were an additional 3,500 Indian followers, who performed support functions such as food preparation and animal care. Altogether, Indian personnel comprised more than 80 percent of Townshend’s force.These Indians were members of what colonial authorities termed “martial classes,” ethnic and religious groups that purportedly possessed innate qualities conducive to military service. While British authors attributed different virtues to specific ethnic and religious groups, all the groups shared a willingness to accept colonial rule. Inhabiting rural areas with authoritarian social structures and low rates of literacy, they had little exposure to notions of self-government circulating in India during this period. To reduce the likelihood that these Indian personnel would unite in rebellion, as had been the case in 1857, the British encouraged distinctive dietary and religious practices among the groups they recruited. They also reinforced the identities of individual units by recruiting from specific communities.

Thus, at the outset of the First World War, the Indian Army was a patchwork of distinct units, with entire companies or even battalions consisting of sepoys or sowars as well as non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and Indian Vice-roy’s Commissioned Officers (VCOs), all of the same ethnic and religious background. At full strength, each Indian battalion also included thirteen British King’s Commissioned Officers (KCOs), who served as a vital link between the command structure of the army and the Indian personnel, who were largely illiterate. The unique makeup of Indian units made it difficult for senior British officers to assess the morale of their members. While many had experience commanding Indians, few were familiar with all the languages and cultural practices of the different ethnic and religious groups that comprised the army as a whole. This was particularly true of Charles Townshend. Despite his extensive service in the Indian Army as a staff officer and a senior commander, he had never served as a regimental officer in an Indian unit.

The harsh conditions IEFD experienced in Mesopotamia increased the uncertainty of British commanders for several reasons. The British logistical system was inadequate, which left British and Indian personnel without tents, clothing, and even boots. Indians, in particular, also suffered due to inadequate food supplies. Traditionally expected to supplement their rations by purchasing food locally, they were unable to do so in Mesopotamia; the food shortages led to outbreaks of deficiency diseases such as beriberi and scurvy. Soldiers also suffered from dysentery and malaria—further complicated because the aforementioned logistical shortcomings left them, as well as those wounded in battle, without adequate medical care. To make matters worse, soldiers who became casualties in Mesopotamia were not immediately discharged back to India, which had long been an expectation of Indians who became sick or wounded on campaign. Those soldiers who escaped death or injury felt keenly the loss of comrades and leaders with whom they had served for years or even decades. The small communities that traditionally provided recruits for specific companies and battalions ran out of able volunteers as the war progressed. As a result, it became increasingly difficult to maintain the cohesion of Indian units. As historian Edwin Latter has explained: “Recruiting was too localized, and specialized, to permit the replacement of wastage without changing the social, and even ethnic makeup of company-level units.”

The British also had trouble finding officers with Indian language skills and experience leading Indian personnel. By the fall of 1915, it had become increasingly difficult to find any replacements for officer casualties in Mesopotamia; an average of only seven British officers remained in each Indian battalion. Sir Walter Lawrence, commissioner of Indian military hospitals in France and England, described the overall impact of these losses in a letter to the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener. Indian personnel, he explained, “have become accustomed to look upon their regiment as a family: they have lost the officers whom they knew, and the regiment, which formerly was made up of well-defined and exclusive castes and tribes, is now composed of miscellaneous and dissimilar elements. . . . This is no longer a regiment. It has no cohesion.” The conditions in which soldiers served in Mesopotamia, along with the impact of sustained casualties, corroded Indian morale as 1915 progressed.

In this context, some soldiers expressed religious objections to the campaign. Muslims comprised approximately 40 percent of the Indian Army at the beginning of the war. Many Sunnis had reservations about fighting against the Ottoman sultan, who they recognized as the spiritual leader of the Muslim world. Shias were reluctant to fight near holy sites like Karbala and Najaf. Reassured by the British that the Ottomans had initiated hostilities, and that they would not attack religious sites, most Muslim soldiers participated in the campaign. But trans-frontier Pathans, whose homes lay in independent tribal territory between India and Afghanistan, were more likely to resist. Religious objections to service may also have been motivated by Pathans’ concerns for the safety of their property and families, which were outside the control of British authorities.

Lieutenant-General Arthur Barrett, Townshend’s predecessor in command of 6 Indian Division, unsuccessfully requested to replace four companies of Pathans twice in early 1915. The fact that the Pathans remained in Mesopotamia increased British concerns about the morale of the entire force. Thus, like any commander assuming a new role in an unfamiliar environment, Charles Townshend experienced real uncertainty as he arrived in Mesopotamia in the spring of 1915. But his lack of experience leading Indian personnel, combined with suspicions about their loyalty, compounded this uncertainty. It would become an acute source of friction under the stress of active operations. . .

Surrender

|

| Prisoner Column After the Surrender at Kut |

Human limitations clearly affected 6 Indian Division’s performance. Soldiers participating in active operations without comrades or familiar leadership were more likely to succumb to the effects of fear, fatigue and hunger. This was apparently the case when soldiers retired voluntarily at Ctesiphon on 22 November, and then engaged in looting at Aziziyah on the 28th. These factors also affected their commander. While Townshend generally maintained his composure at Ctesiphon and during the initial stages of the retreat, the Umm at Tubul engagement and the extended retirement that followed left him both exhausted and anxious. This was evident in Townshend’s unwillingness to allow his subordinates even a brief respite on the afternoon of 1 December for fear that they would be unable to resume the retreat. . .

[Besides poor intelligence regarding the enemy forces] Townshend became more apprehensive as he witnessed scenes of indiscipline at Ctesiphon and during the retreat. Significantly, this indiscipline never spread. Even during the siege that followed, only a small minority of Indian soldiers deserted or committed acts of insubordination. Townshend can be criticized for failing to distinguish between the Indians under his command, but he was not alone. While officers serving in Indian units were expected to possess specific linguistic skills and cultural knowledge, few if any senior commanders were familiar with the numerous languages and cultural traits of the diverse groups that made up the Indian Army. Like many British officers, Townshend relied on generalizations and stereotypes that did little to enhance his understanding of his subordinates. As a result, he grew increasingly uncertain about their morale as the retreat progressed.

For readers who wish to gain a greater familiarity with the WWI's Mesopotamia campaign, we have collected our articles on the subject HERE:

. . .

Wednesday, September 27, 2023

Tuesday, September 26, 2023

Aviator, Historian, Collector Javier Arango on Flying the Ground-breaking Fokker D.VIII

|

| Fokker D.VIII, photo © Philip Makanna (Note Wing Thickness) |

A selection from the forthcoming collection of essays by the late Javier Arango, The Nature of World War I Aircraft (Ghosts, 2023)—

"The Fokker D.VIII"

Anthony Fokker was one of the most prolific aircraft designers working during World War I. His aircraft became closely associated with many of Germany’s famous aces, such as Oswald Boelcke, Max Immelmann, Ernst Udet, and Manfred von Richthofen. Fokker was an agile and daring entrepreneur and excelled at quick and dynamic experimentation. By the end of the war, he and his team of designers must have amassed a tremendous amount of knowledge concerning fighter aircraft design.

The Fokker D.VIII was his last operational fighter before the Armistice, and as such should have represented the epitome of his design philosophy. The aircraft, however, is something of a paradox. It is extremely modern in some respects but retains some traits that seem rooted in an earlier time.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the D.VIII is the fact that it is a monoplane. Fokker had achieved early success with a wing-warping monoplane, the Eindecker, which became the terror of the skies over the Western Front. He then evolved the Eindecker into a biplane that had only moderate success. Probably Fokker’s most famous and recognizable design was a triplane. Subsequently he experimented with biplanes, triplanes, sesquiplanes, monoplanes, and even one airplane with five wings. That his last design of the war was a monoplane is revealing. Fokker was an expert pilot himself. He had the privilege of experiencing very many configurations in flight and had developed an uncanny ability to sense relative advantages in performance and subtle differences in handling qualities. The D.VIII’s monoplane configuration was no accident. Fokker was exploiting an aerodynamic reality—monoplanes are more efficient than airplanes with multiple wings, each of which inevitably interferes with the airflow of the other.

This fact must have been known to Fokker and to other designers, but the key difficulty was in the execution. The predominant biplane configuration of the day had many practical advantages that compensated for its aerodynamic inefficiency. The engineering of externally braced biplanes was simple and intuitive. It used rectangular, cross-braced trusses, commonly known and seen in many structures, such as bridges. This building technique was easily scalable. The construction of the wings themselves could be imprecise because small errors could be simply “rigged out” by adjusting the lengths of the members joining the wings to one another and to the fuselage.

Monoplanes, on the other hand, had either to support the wing externally with wires, as in the Eindecker, or to provide sufficient internal structure to support the wing as a cantilever. The obvious aerodynamic preference would have been to eliminate the external wires altogether. But then the wing would need a strong, deep spar, which would have made it heavy and thick, two attributes that were considered inimical to efficiency.

Fortunately, Fokker had previous experience with thick cantilever wings. Thanks to his willingness to try any conceivable idea, and even to pull together existing ideas that in isolation had little success, he had experimented with thick wings years earlier. There is speculation as to where Fokker got his idea for the thick wing and whether he copied it from the engineer and industrialist Hugo Junkers, who was building thick cantilever wings made entirely out of metal early in the war. As with many other Fokker innovations, the source of the initial idea may be in doubt, but the successful embodiment of the idea in a practical, useful product is not. Unlike Junkers’ airplanes, Fokker’s were extremely practical and effective. The Fokker Dr.I already used three cantilever wings with thick airfoils. The D.VI turned the triplane into a biplane, still using thick airfoils. The D.VII, arguably the best aircraft of WWI, also used thick airfoils. It was no accident that Fokker felt comfortable enough with his cantilever wings and thick airfoils to produce an internally braced monoplane.

| |

| Early D.VIII Prototype (period photo not in the book) |

Contrary to the view prevalent at the time, the thick airfoil was actually superior. Fokker knew from experience that thick airfoils actually did not add much drag, if any, at high speed, and that they had much better characteristics than thin airfoils when flown slowly, at larger angles of attack. Fokker had the technology to build a single cantilever wing while keeping it within weight restrictions. He avoided metal or other exotic materials—high-strength aluminum alloys were not yet available (Junkers had used extremely thin sheet steel)—and instead used wood. His factory workers required little training to produce the new wing. Fokker achieved a wing that was easy to build, relatively light, structurally efficient because its thin plywood skin, unlike the more conventional linen, was a load-carrying part of the structure, and aerodynamically highly efficient as well. As always, Fokker innovated by combining existing ideas with proprietary experimentation in order to produce a practical, useful machine. The resulting Fokker D.VIII is an astounding aircraft. Its wing looks completely out of place among other WWI airplanes; it seems to belong to a 1940s-era fighter.

I have been fortunate to fly a Fokker D.VIII powered by a 160-hp Gnôme rotary engine. The D.VIII has an amazing climb rate and is also fast in level flight. When maneuvering, the D.VIII shares a very positive characteristic with the other thick-airfoil Fokkers—it can achieve very high angles of attack while giving the pilot a comfortable feeling that the wing will not suddenly stall and go out of control. Contemporary airplanes with thin airfoils, like the Sopwith Camel and the Nieuports, can turn sharply but, without warning, will suddenly fall out of control. The D.VIII will continue to “mush” through a turn, gradually alerting its pilot that it needs more speed. This quality is extremely useful in dogfights, where controlled, tight turns to the maximum ability of a wing confer an important advantage. Landing the D.VIII is also simpler because it stalls gradually toward the ground, giving the pilot a larger margin of error in the flare.

The D.VIII’s most remarkable characteristic, however, is that, unlike most other WWI airplanes, it has ailerons that actually work very well. Fokker had not only perfected his wing design but had also finally come up with the correct configuration for the ailerons. They were very long and narrow and completely embedded into the wing, so that no turbulence-producing gap opened when they deflected. The D.VIII therefore rolls like a modern airplane, sharply and with little of what is called adverse yaw—the tendency of the nose to swing away from the direction of a banked turn, owing to the greater drag of the downgoing aileron.

Given all these successful design characteristics, would I qualify the D.VIII as Fokker’s best fighter? No. The Fokker D.VII, for example, is more powerful, faster, easier to fly, and has a better engine. For dogfighting, the tiny Fokker D.VI, with its short wingspan and very light weight, may be superior to the D.VIII. The constraints of a practical world where Germany was losing a war of attrition and running out of supplies interfered with the D.VIII’s success. The D.VIII was the best Fokker could do given a relatively weak and practically obsolete Oberursel rotary engine. The Oberursel was no match for the new generation of Allied engines or even for the German in-line Mercedes and BMWs that yielded nearly twice the horsepower, but it was relatively plentiful at a time when the better engines were practically unavailable. So the ever pragmatic Fokker designed the D.VIII to be the best airplane it could be, using an outdated engine and facing enemy aircraft that were becoming more dependent on power and speed than on sheer maneuverability. He knew what he was doing. In order to compete with the more powerful fighters, he made the D.VIII remarkably light. It weighed only two-thirds as much as the Mercedes-powered D.VII. To make it easy to build, the fuselage was simply square, not streamlined, and was based on structural techniques already used in previous Fokker aircraft. The cockpit was miserably equipped. The D.VIII was evidently designed to quickly get an effective aircraft to the front. Unfortunately, haste in production and design also led to wing failures that ended up grounding it.

The Fokker D.VIII is a desperate airplane, made not to be the best air-superiority fighter but to be the best fighter that could exist amid the very challenging realities of a nation about to collapse. Fokker did succeed in delivering an easy airplane to build, with an available, though obsolete, engine. The D.VIII’s light weight gave it excellent climb capability. Its rotary engine, which did not need to be warmed up, allowed it to get into the air quickly in order to defend against invading airplanes. Once airborne, it had the advantage of being fast and rolling quickly into turns. And, very important, it could be flown effectively by inexperienced pilots who surely enjoyed the docile handling characteristics provided by its excellent, futuristic, thick-airfoil wing.

[Originally published as "The Fokker E.V/D.VIII" in Jim Wilberg, et al. Aviators of the Great War: The Aviation Art of Steve Anderson. Aeronaut Books, Indio, CA, 2014. Reprinted with permission]

The Nature of World War I Aircraft—Collected Essays by Javier Arango, with photos by noted aviation photographer Philip Makanna is expected to be available for purchase in December. We will alert our readers as soon as it can be acquired. Here are the cover and table of contents for the book:

Monday, September 25, 2023

The First Ace: Second Lieutenant Adolphe Célestin Pégoud — A Roads Classic

|

Pégoud Receiving the Croix de Guerre |

|

| Immortalized in Comics |

Sources: Tony Langley Collection, Wikipedia, Traces of War and theaerodrome.com

Sunday, September 24, 2023

The Very Big Problem of Shipping the AEF Over There

By Leo P. Hirrel

Prior to resuming unrestricted submarine warfare, the German government calculated that even if the United States could adjust its industrial might to war production, it would be unable to transport and resupply an army across the ocean. To be sure, the Army Transport Service originated in 1898, and its troopships began crossing the Pacific the following year in response to American annexation of the Philippines. Yet these ships were not suitable for moving troops across the Atlantic, because their slow speed left them vulnerable to submarines and they could not carry enough coal for the return voyage. Even if this small fleet were suitable, it could not carry nearly enough soldiers to make a difference.

Nonetheless, the United States was determined to send an infantry division to France by early summer if only to reassure its allies. A civilian advisory committee identified seven suitable passenger ships that were available. Although sufficient to move the token force, clearly this fleet would never work for the millions of soldiers destined for France.

Help was on the way from a most unwilling source. In 1914, ships from the German passenger fleet sought protection from the British Navy in the then-neutral harbors of the United States. As war with the United States appeared more likely, the Germans recognized that these ships might be seized, but they believed they could keep these ships from being used against them without their total destruction.

They ripped apart the giant steam cylinders within the engine rooms, believing that it would require over two years to replace them. Disregarding maritime customs, the U.S. Navy chose to repair the existing steam cylinders instead of replacing them, which placed the ships in operation relatively quickly. Altogether the United States gained 20 passenger ships this way, including the giant Vaterland, which became the famed Leviathan. These ships played a critical role in the early part of moving the U.S. Army to Europe.

|

| The USS Allen Convoying the USS Leviathan |

The Army acquired other passenger ships through a variety of means. The government exercised its right to commandeer use of existing passenger ships and those under construction, with payment to the owners. The United States solicited neutral nations for permission to charter their ships, and for the most part, neutral nations agreed because the war drastically reduced passenger commerce. The Netherlands, however, was unwilling to agree, so the United States simply employed a seldom-used belligerents' right to commandeer neutral property within its boundaries by seizing Dutch passenger ships in American ports, with compensation.

Ships were re-configured for the maximum numbers of passengers, and soldiers slept in shifts. Altogether, 347 ships made a total of 1,228 voyages. Even with these acquisitions, the United States still lacked the means to move its army across the ocean. To meet the gap, Great Britain provided its own passenger ships and cargo ships that had been converted to passenger ships. By the summer of 1918, the combined fleet was sufficient to move over 200,000 soldiers per month.

Cargo proved to be the more difficult problem. Before 1917, about half of the American merchant marine was engaged in coastal trade, not transoceanic. Whereas passenger traffic declined in the war, the demand for cargo ships increased, including such added requirements as moving nitrates for munitions from Chile to the United States. Until the convoy system was introduced, the German submarines sank ships faster than the British could build new ones. Moreover, the demand for shipping accumulated with each successive increase in the numbers of American soldiers. On average, each soldier in France resulted in 28 to 33 pounds of cargo per day. An increase of 200,000 soldiers meant at least another 2,800 tons daily cargo requirements, and the numbers just kept climbing. The inability to move supplies across the Atlantic became a major impediment to American operations.

As early as September 1916, Congress had recognized the potential need for a shipping industry by authorizing a shipping board, with the option to create an emergency fleet corporation should construction of ships be required. The early history of the corporation, however, illustrates how the administration's initial reluctance to use wartime authorities to commandeer material hindered the mobilization. Ships required steel, which was in short supply and therefore priced high.

After a failed wooden ship effort, the board did turn to steel ships, including requisitioning ships then under construction at American shipyards. It also developed means of fabricating parts throughout the nation and using the shipyards for final assembly. In the process it established new shipyards, notably at Hog Island near Philadelphia. These new yards required construction of the facilities, staffing, establishment of administrative procedures, recruiting labor, and even housing for the employees. All of this required time. The Emergency Fleet Corporation did not reach full production until October 1918. In that month alone, the Corporation launched 77 ships that could carry 398,000 deadweight tons, almost one-third more than the entire United States had produced during all of 1916. These were impressive production numbers but at the end of the war.

|

| Massive Hog Island Shipyard, Philadelphia, PA |

In the meantime, the United States needed to contend with inadequate shipping and every prospect of watching the situation deteriorate. Movement of supplies to Europe was the greatest concern but not the only need for shipping. The Navy also needed commercial cargo shipping, as did the Belgian relief efforts. The nation needed to import essential raw materials, most notably nitrates from Chile but also a wide variety of other material. Some prewar trade patterns were too essential to allow discontinuance. Each segment of the oceanic trades had its own fleet, which created a situation that was inefficient in the aggregate.

In response to the rapid deterioration of the situation, the government developed the Shipping Control Committee in January 1918. The concept ended the practice of separate fleets for each particular purpose and placed all available ships into a single pool. The committee then determined the optimum use of each ship in supporting the various facets of the war effort. Ships were assigned based upon this need, not upon any ownership principles. Within a few weeks the changes somewhat eased the shipping situation until new construction could take effect.

Sources: Over the Top, September 2017

Saturday, September 23, 2023

The Tsar Visits the Fallen Fortress of Przemyśl (Video)

Friday, September 22, 2023

Remembering a Veteran: André Breton, French Medical Service, Father of Surrealism

|

| Soldier, 1916 |

I was sent to a centre for disabled men, men sent home due to mental illness, including a number of acutely insane men, as well as more doubtful cases brought up on charges on which a medical opinion was called for. The time I spent there and what I saw was of signal importance in my life and had a decisive influence in the development of my thought. That is where I could experiment on patients, seeing the nature of diagnosis and psychoanalysis, and in particular, the recording of dreams and free association. These materials were from the beginning at the heart of surrealism’

It's hard to summarize Breton's view of Surrealism, but perhaps some of his better known quotes will help a little:The imaginary is what tends to become real.The man who cannot visualize a horse galloping on a tomato is an idiot.Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all.All my life my heart has yearned for a thing I cannot name.The mind, placed before any kind of difficulty, can find an ideal outlet in the absurd. Accommodation to the absurd readmits adults to the mysterious realm inhabited by children.I could spend my whole life prying loose the secrets of the insane. These people are honest to a fault, and their naivety has no peer but my own.

Thursday, September 21, 2023

Légion étrangère in the Great War

|

| Swedish Volunteers for the Legion |

The French Foreign Legion of the colonial era was mainly deployed in extra-European areas and consisted of mercenaries on five-year contracts. After its foundation in 1831, the Legion’s main task was to serve French imperialism with deployment in colonial conquests and counter-insurgency in Africa, Mexico, Indochina, and the Middle East. In World War I, the Foreign Legion fought in many critical battles on the Western Front, including Artois, Champagne, Somme, Aisne, and Verdun (in 1917), and also suffered heavy casualties during 1918. The Foreign Legion was also in the Dardanelles and Macedonian front and was highly decorated for its efforts.

The situation during World War I, however, was different: A large proportion of the Legion was deployed not on colonial soil but on the Western Front and other European theaters of war. This was mainly due to a decree from 3 August 1914 that allowed foreign volunteers to enlist “for the duration of the war.” As French law forbade foreigners from joining the regular army, these enlistments had to be in the Foreign Legion.

|

| The Legion on the March in Champagne |

In the days before the enlistment decree, there had been several calls to serve for France, including one by a group of intellectuals living in France led by the Swiss novelist and poet Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961). Cendrars himself immediately joined the Legion and lost his right arm in September 1915, an experience he would describe in his autobiographical book La Main coupée (1946). Those willing to serve for France included, amongst others, Italians, Russian expatriates, East European Jews who had fled to France in the 1890s, nationals of neutral countries (including the American poet Alan Seeger (1888–1916)), members of minorities of the Habsburg Empire, and allegedly even 800 Germans and Austrians.

Their motives included a love for France and its political system and the wish to participate in a war that was anticipated to be short but in some cases also the need to avoid unemployment after the closing of factories upon mobilization. Altogether nearly 43,000 foreigners enlisted in the French army during World War I, although not all of these served in Foreign Legion units. In the summer of 1914 the Foreign Legion, as usual, was dispersed to colonial locations in Morocco, Algeria, and Indochina. When the war broke out, the Algerian battalions were ordered to send half of their manpower to France to incorporate the new recruits and form four new Legion regiments. Those staying in North Africa included a large proportion of Germans and Austrians, who in general displayed a remarkable loyalty to the French mercenary troop. Unlike the figures of the other units of the “Armée d’Afrique” fighting on European soil, the number of legionnaires did not increase but displayed a sharp fall from 1914 to 1918. While the overall number of legionnaires from 1913 to 1915 doubled to nearly 22,000, there was a drop to about 12,000 in the second half of the war. Five march regiments were formed and then reorganized into a single regiment on 11 November 1915 due to severe losses to create the RMLE or the Foreign Legion Marching Regiment.

|

| Legionnaire Edward Morlae Wrote a 1916 Memoir on His Experiences in the War |

The inclusion of allegedly idealistic wartime volunteers into the Legion would considerably, albeit only temporarily, change its image. The London Times during autumn 1916 characterized legionnaires as “fighters for an idea," attributing to them “a deeply-rooted love of liberty and justice”: “The old idea that the Legion is a regiment of wrongdoers is exploded […].” However, the wartime Legion did not just consist of idealistic volunteers, and indeed, the amalgamation of “old” legionnaires arriving from the colonies and the wartime volunteers proved to be extremely difficult. The two groups’ mentality and outlook were radically different: Many of the new volunteers were patriotic, middle-class, politicized, and not at all happy to be incorporated into the infamous mercenary unit. “Old” Legionnaires, on the other hand, overwhelmingly stemmed from the lower classes, considered fighting a profession and hardly empathized with the idealistic volunteers.

A lack of experienced cadres added to these problems which, together with high casualty rates and widespread discontent, would soon result in a serious crisis that threatened the Legion’s fighting efficiency. In May and June 1915 there were several cases of mutiny. These problems forced the Legion to restructure and to restore much of its prewar character. Many volunteers had left again after their own countries had entered the war. British and Belgian volunteers had very quickly been allowed to join their own national armies in 1914. The same applied to Italians in spring 1915. In mid-1915, wartime volunteers were also given the opportunity to fight in other French units, and many volunteers decided to do so. Those who remained in the Legion from now on were voluntarily there. New entrants only had to serve for a very short time in the Legion before being transferred to other units.

|

| American Volunteers |

All these measures transformed the Legion on the Western Front from a gathering of reluctant foreigners to an elite regiment, considerably reduced in numbers, but strengthened in morale and fighting efficiency. It was not by chance, therefore, that the Legion would not be affected by the general morale crisis and mutinies of the French army in spring 1917. In November 1915 two Foreign Legion units had been merged into the “Régiment de marche de la Légion étrangère” which subsequently would fight at the Somme, at Verdun, in the second Marne battle and other theaters of war. Towards the end of the war, however, a serious dearth of recruits would jeopardize the Legion’s continued presence at the Western Front. Officially 4,116 members of the Foreign Legion were killed on the Western Front and another 1,200 in other theaters of war. Thus, roughly 10 percent of those serving in the Legion between 1914 and 1918 lost their lives.

Sources: Chemins de Mémoire; A Soldier of the Legion: Edward Morlae; Encyclopedia 1914-1918