|

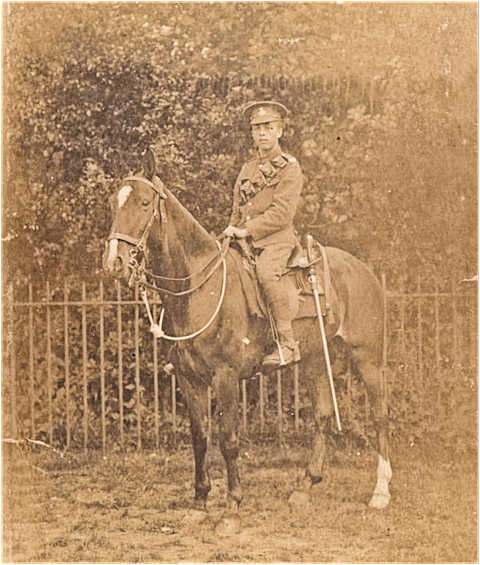

| General Smuts on an Inspection Tour of the Western Front |

The scene is set historically and geographically. South Africa had emerged from its war between the Afrikaner Republics and the British as a country divided between empire loyalists and Boer nationalists. Its neighbors included German Southwest Africa, later Southwest Africa and now Namibia, and German East Africa, later Tanganyika, and now the mainland portion of Tanzania.

The central figure of this work, General Jan Smuts, was, like his mentor and superior Prime Minister Louis Botha, a multi-faceted man. A scholar in literature and science, placed by at least one commentator on a par with John Milton and Charles Darwin, a lawyer, a politician and a military leader, Smuts is one of the most impressive figures of both world wars.

A fighter for the Afrikaner Republics during the South African War, Smuts, along with Botha, became political leaders who strove to unite Dutch and English settlers in a Dominion of the British Empire. A political and military leader, in the tradition of Napoleon, he balanced a vision of political expansionism with his public’s desire for low casualties. Though an Empire loyalist, Smuts remained a practitioner of the South African way of war. An advocate of maneuver rather than frontal attack, he lacked the will to annihilate his enemy but led his men to victory.

|

| South African Troops in Action |

Envisioning the expansion of South Africa to encompass Africa to the equator and the position of the dominant Dominion in a Cape-to-Cairo British domain, Smuts’ war aims meshed with those of his British colleagues. As rulers of the waves, Britannia sought to drive the German Navy from the South Atlantic by capturing the German Western African ports of Luderitzbucht and Walvis Bay and the destruction of the German wireless stations in those ports and Windhoek. While achieving those goals, Smuts led his South African forces to capture the whole territory. Success having been achieved in the West, Smuts and his forces turned to German East Africa which it conquered in joint actions with British and Belgian units.

With South Africa holding sway over much of the southern portion of the Continent, Smuts was dispatched to London to be part of the Imperial War Cabinet and to participate in the peace conference. Resisting offers of the Egyptian Command, deeming it a sideshow, and a secret mission to Russia, which he regarded as a spent force, Smuts played roles in the development of air power and the settling of Welsh strikes. In peace discussions, Smuts’s expansionist goals were thwarted but South Africa emerged as an enhanced Dominion, and his international reputation would carry him into prominence in the Second World War.

Smuts’ war was in a secondary theatre. Why should a Roads reader take the time to add this study to his Great War canon? I see several reasons. It is well written. Katz has skillfully woven cultural, political, and military themes into his account. The text is helpfully supplemented by maps, tables, photos, a bibliography, and cartoons. A student of military operations will appreciate the detail with which they are presented.

Smuts is depicted, in my view, as more of a Pershing, in his preference for movement, than a Haig, Nivelle or Smuts's British colleagues in South Africa in their practice of static warfare and direct attack. Smuts, the Afrikaner political leader, first had to draw public opinion into support for the war before marching onto Mars’s fields. One is reminded of Confederate heroes, Joseph Wheeler and Fitzhugh Lee, who re-donned the blue to rally Southern support for the Spanish American War. Katz illustrates that some warriors fought in a manner unlike the bloodbath of the Western Front. This book reminds us that the Great War was, after all, a world war that profoundly shaped world history beyond Europe and even the Middle East. It provides a perspective lacking in most Great War histories.

Jim Gallen