|

| John B. Brinkley at the Top of the World |

James Patton

Born in North Carolina, John R. Brinkley Jr. (1885–1942) was a colorful character who called Kansas home from 1917 through 1935. Originally trained as a telegrapher, over the course of his life he was a millionaire, a charlatan, a quack, a fraud, a crackpot, a cheat, a political ranter, a radio pioneer, a child abductor, a bigamist and, believe it or not, a hero.

He advertised himself as a doctor although he had a sketchy medical education. At first he worked in medicine shows and sold tonics around the Carolinas. Then, in 1912, he got the chance to buy a medical diploma from a going-bankrupt medical school in Kansas City.

|

| His Hometown Is Still Proud of Him |

On 23 April 1908, Congress had created the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC), and in 1913, on the strength of his dubious degree, Brinkley was accepted for a ten-year hitch.

He set up shop in Greeneville, SC, with an "electro-medical" doctor, and they developed a lucrative practice treating syphilitics with a shot of colored fluid that they claimed was the German "miracle-drug" Salvarsan. Brinkley fled under a cloud of suspicion, stopping over in Memphis, where he was arrested and, although he was not divorced, married his second wife. Weaseling his way out of all the charges against him, the happy couple fled to Arkansas. He answered a blind advertisement for a doctor in Fulton, KS, a rural community north of Pittsburg. While there, on his own initiative, he organized the first army ambulance company in Kansas.

In April 1917, the entire MRC was called up to active duty. First Lieutenant Brinkley was ordered to report to Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, but the army soon moved him to Ft. Bliss in El Paso, where he was assigned to the newly formed 64th Infantry Regiment as its chief medical officer—in sole charge of the health care of over 2,200 new recruits.

|

| Fort Bliss During the War |

According to his official biography: ‘Dr. Brinkley was responsible for the sanitation of the whole regiment—the installation of latrines, sewage systems and garbage disposal. When asked why they had joined the army their invariable reply was that it was to get $30 a month with room and board thrown in. “They had about as much patriotism visible as a horned toad.” [Said Brinkley]

An epidemic of meningitis swept through the ranks; measles and many other infectious diseases began to make inroads among them. Many of his soldier patients were in the hospital, and the overflow was sick in their quarters. And there were many who were crippled and unfit for the army service–dozens of men on the roll who should never have been allowed to enlist. A captain one day who had been drilling a company brought a man into the doctor for examination, troubled because he could not get the man to step correctly in drill. Dr. Brinkley found that the man’s hip had been almost shot away and was completely ankylosed, that is, that bones had unnaturally knit together. Other men had severe heart disease, flat feet, broken arms and legs.

So far this may sound sort of heroic. His official biography concludes: "his military service was a terrible ordeal that he could scarcely endure. He was lucky if he got three or four hours of sleep at night. After a short time he collapsed from exhaustion and spent a month in the hospital, followed by a discharge with a certificate of disability. He continue to serve in the Medical Officers Reserve until August 1922."

The official army records tell a different story, stating that Brinkley served a total of one month and five days. He worked for only two days and then was placed under observation for "nervous exhaustion" at the Ft. Bliss base hospital for the remainder of his service. His reserve officer’s commission wasn’t renewed upon its expiration in 1922.

Back at home in the autumn of 1917, Brinkley answered another advertisement, this time for a doctor in Milford, KS, a small town on the Republican River which, coincidentally, was 16 miles west of the brand-new Camp Funston.

|

| Doc Brinkley's Finest Moment Would Come During the Spanish Influenza |

Quoting from Pope Brock: "The worldwide Spanish flu pandemic … had struck here too, and Brinkley earned respect and gratitude that winter with his conspicuous efforts to help the victims. 'The doc seemed to have an uncanny knack with the flu,' one of his aides recalled. 'Maybe it was something he learned as a boy in rural North Carolina [his father had practiced traditional healing]? I don’t know. But whatever it was it worked.' When more than a thousand cases broke out at nearby Ft. Riley, Brinkley (in marked contrast to his exaggerated exploits in the army) was on the spot to help treat them. He went from farm to farm, as well, bouncing along mud-rutted roads in a 1914 Ford. His driver, Tom Woodbury, remembered him as 'a wonderful doctor. He lost only one patient during the flu epidemic and he doctored all around.' A local housewife said, 'He saved us. They called him a quack and that just breaks my heart. He was no quack, believe me.' When a coal shortage that winter made the suffering even worse, Brinkley led a petition drive demanding that the governor provide emergency allocations for flu victims. The entire performance, contrasted with the rest of his career, was so aberrant it is hard to credit. Maybe he was buying publicity. Maybe he had no choice. Whatever motivated Brinkley, the help he rendered during those months stand as the finest achievement of his life."

Subsequently Brinkley became known as the "goat-gland doctor" after he achieved international notoriety and considerable wealth by transplanting goat sex organs into humans. Although at first he promoted this procedure as a means of enhancing male virility, over the years he also claimed that it was an effective treatment for a range of conditions. Although his ideas sound utterly hare-brained today, in his time endocrinology was in its infancy, and various endocrine replacement theories were being pursued, including insulin therapy for diabetes mellitus.

At various times, Brinkley operated clinics in Kansas, Texas, and Arkansas. His clinics offered steady employment and paid good wages. He was also community-minded, financing several public works projects in Milford. His Texas mansion grounds featured a sort of amusement park complex that was open to the community until it was sold by the Brinkley family in 1980.

He performed his treatments for over two decades, despite having his techniques and credentials thoroughly discredited by both the broader medical community and the pharmaceutical industry. His operations might not have been only fraudulent; they could have been dangerous. Forty-two persons are known to have died at his Kansas clinic.

|

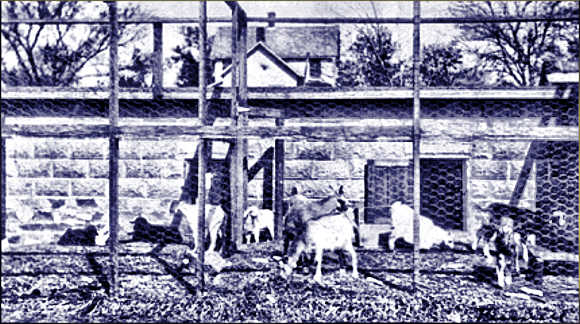

Brinkley's Goat Farm |

In 1923, in order to sell his treatments, his product lines and even his advice, he set up a powerful radio station, KFKB (Kansas First, Kansas Best). Although he was a pioneer in airing traditional American music, his broadcasts consisted mostly of advertising. In 1930, KFKB was deemed not operating in the public interest, and the license wasn’t renewed. He sued and lost in a landmark case regarding regulatory power.

Undeterred, Brinkley set up shop in Del Rio, Texas, as the Mexican-licensed XER: his 500 kilowatt transmitter and “Sky Wave” antenna array (both were illegal in the U.S.) were located on the southern side of the Rio Grande. He began the era of the "Mexican border blaster" radio stations whose nighttime signals could reach virtually everywhere in the U.S., especially in the rural Midwest. The idea was pure genius and soon copied, until there were 11 on the air, all of which the Mexican government later shut down in compliance with the 1938 Havana Treaty. Some later returned to the air under Mexican ownership.

Incensed after being stripped of his medical license in Kansas (he was still licensed in seven other states), Brinkley exhorted his many followers to elect him governor. He ran in 1930 and 1932 (governors had two-year terms until 1972) and in the primary of 1934; the first time, he nearly won. He may have lost due to sleazy last-minute ballot disqualifications.

In Kansas he reportedly took in over $14,000 a week, while the average doctor earned $61 weekly. Texas sources estimate that he amassed $12 million there. He was one of the most successful quacks in history—owning mansions, airplanes, custom-made cars, yachts, and lavish jewelry.

Brinkley rose to stellar heights of notoriety and wealth, but his eventual fall was precipitous. He died in bankruptcy amid a welter of malpractice, wrongful death, libel, tax fraud, and mail fraud charges against him. There remains no trace of his clinic in Kansas; the old part of the city was flooded by the Milford Reservoir in 1962. His mansion in Del Rio remains but is still privately owned.

Sources Consulted Include:

Kansapedia, Kansas State Historical Society

Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association

Charlatan, Pope Brock, Crown (2008)

The Bizarre Careers of John Brinkley, R. Alton Lee, University Press of Kentucky (2002)

What a great movie this would make. I can’t believe it hasn’t already been done!

ReplyDelete