In 1919–starting 106 years ago today–a bicycle race was staged that ran through the former Western Front. Lasting two weeks, it was the brainchild of Marcel Allain, editor of Le Petit Journal, at the time one of France’s largest newspapers.

|

| Note the Cobblestone Streets |

In those days newspapers often organized sporting events to boost their circulation. Nowadays TV networks do much the same thing. An outstanding example of such an event is the venerable Tour de France, first run in 1903 under the sponsorship of a predecessor of the French sports newspaper L’Équipe.

A problem with planning this race was, since the battlefields had been off-limits to civilians for years, no one at Le Petit Journal had any idea of what the conditions were like.

Click on Image to Enlarge

|

| The Route |

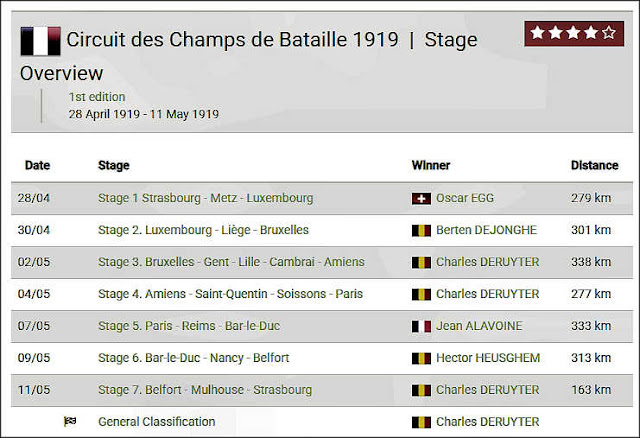

So Tour de France organizer Alphonse Steines (1873–1960) was hired to reconnoiter, and he mapped a course that he said was hard but possible: it would start in Strasbourg and breeze through Luxembourg to Brussels, then head west to Flanders to join the old front near Diksmuide. It would then follow the line through Ypres, Lille, the Somme, Amiens, Cambrai, St. Quentin, the Marne, the Argonne, Verdun and St Mihiel, ending back in Strasbourg. This route was 2,000 km long and would consist of six stages of about 300 km each, plus a seventh shorter run. There would be a rest day between each stage and an extra day off in Paris. Riders had to carry all of their kit with them—no helpers were allowed. Stages had to finish around 1600 hrs so that results could be published in the next morning’s edition, so the riders often had to start at 0300 hrs.

|

| A Belgian Competitor in the Argonne Sector |

On 28 April, 89 riders set off from Strasbourg–most of them were attracted by the prizes, about £1,500 for the overall winner and £300 for each stage winner. Most of the entrants were French or Belgian war veterans. None were British because stage racing wasn’t allowed in the UK. No Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, or Bulgarians of the former Central Powers were eligible.

The first two stages went through Luxembourg and Belgium in territory little affected by the war. At Stage 3 the course entered into the battlefields and some areas designated "Zone Rouge" by the French government—meaning land so war-damaged it was not fit for habitation or cultivation. In 1919, this zone covered 1,200 square km of northern France. In his 2019 book Riding in the Zone Rouge author Tom Isitt recounts:

It was across this brutalised land that the riders raced. Gale-force winds, freezing temperatures, and driving sleet greeted them as they turned south from Diksmuide and headed for the Salient. Ypres was nothing but a pile of rubble and the riders struggled past Hellfire Corner and up the remains of the Menin Road at a snail’s pace. On to Bapaume, via Cambrai, the roads were entirely made of smashed and broken cobbles... for 120 km.

|

| Even the Main Roads Were Rough |

It was dark by the time the leading riders reached the Somme, and with no lights on their bikes (and no moonlight either) they had been riding slowly and blindly through the wind, sleet, and sticky mud between Bapaume and Albert. The winner of that stage finished in Amiens at 2300 hrs, 18 hours, and 28 minutes after he set off from Brussels.

Some of the riders had to abandon this stage altogether, and others spent the night sheltering in old dugouts before resuming the next day. The last man into Albert had spent a grueling 39 hours cycling through terrible conditions.

Near Paris the roads and weather both improved, but only 24 of the original riders were left. The course passed through Reims, but skipped most of the 1918 battlefields near the Marne. The Chemin des Dames was entirely off-limits. The American sites at the Argonne Forest and St. Mihiel were passed through fairly quickly.

Click on Image to Enlarge

|

| Results |

The last challenge was in the Vosges – going through the pass known as the Col du Ballon d’ Alsace (1,171m), which was also a featured spot on the Tour de France. It was a significant climb for a heavy bike with only two gears and the riders found that there was still a lot of snow up there near the top. They had to dismount in waist-deep snow and carry their bikes slung over their backs for several kilometers.

The final stage on 11 May was 163 km along good roads. The Belgian professional racer and non-war veteran Charles Deruyter (1890–1955), winner of the most stages and grand champion, made the last run into Strasbourg in five hours. His career would last through 1927, but he would win no more solo races.

It had been an arduous journey since the opening day when the riders had set off with their eyes dazzled by the prizes. After two weeks, only 21 of them remained. There had been instances of cheating, mounting bad publicity about the course conditions, and no uptick in newspaper sales.

|

| Champion Charles Deruyter |

It was seen as such a failure by both the riders and the organizers that they never ran it again. It was supposed to be a tribute to the millions who died in the war, but instead it became merely an example of bad planning and bad luck.

Extracted from an article by Dr. Martin Purdy of the Western Front Association. You can read the whole article HERE.

Order Tom Isitt’s book HERE:

"Never, in the memory of man, has a race been more difficult and more gruesome; never has it worked more murderous on the mind and body of a rider..."

ReplyDelete— Karel Van Wijnendaele, pioneer of Flemish sports journalism

France needed a goodwill event to help heal the aftermath of the devastation of war. Editors from Petit Journal tried to bring hope by sponsoring a bicycle race. Organizers should have planned the event more carefully, because instead of healing wounds of the war, it opened them up again. All that the spectators and racers saw were shelled towns with a sense of death in the air. Planners could have rerouted the race so onlookers could see the rebuilding of shattered towns. Stops along the route could have been carefully planned so racers and spectators alike could honor the fallen and bring a sense of healing to communities.