|

| SPRINGFIELD (MA) REPUBLICAN, 11 April 1917 |

By Jerry Jonas

Originally published on the 100th anniversay of the disaster in Phillyburbs. Some additional details and these photos have been added by the editor. MH

Last Wednesday [10 April 2025] marked the [108]th anniversary of one of the greatest wartime disasters in American history, and it occurred during World War I here in the Delaware Valley, just a couple of miles south of today’s Philadelphia.

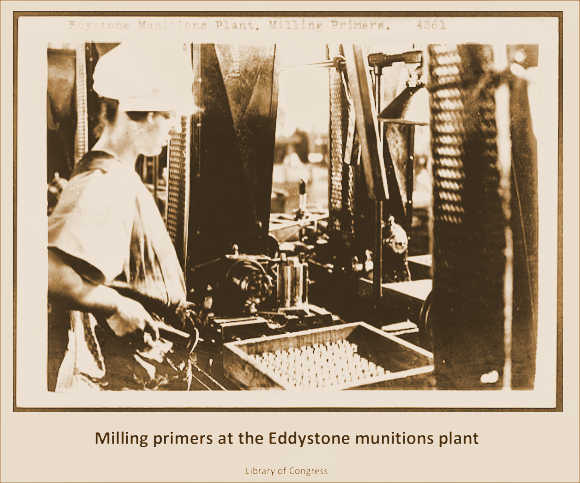

For weeks, the plant management had been running ads in the Philadelphia newspapers recruiting young girls to fill hundreds of jobs. Britain contracted with the Remington Company to produce rifles, and Remington subcontracted part of the work to Baldwin. When their need for munitions outstripped their industrial capacity, Britain and France (and later Russia) also contracted with Baldwin to produce artillery shells. The munitions manufactured at Eddystone were shrapnel shells, an anti-personnel device. One Eddystone plant built the entire shell—from building the shell to shaping the brass cartridge—and filling the cartridge with black powder. Most of this work was being done by women and girls.

About 400 women and girls worked in the plant’s F building. That building housed about 40,000 loaded shells and was divided into three sections: the pellet room, the loading room, and the inspection room. In the pellet room, about 100 girls made the black-powder fuses that would eventually be used to detonate the shells. In the loading room, dozens of additional girls inserted the fuses into the shells, which were then filled with loose black gunpowder. The finished shells were then taken to the inspection room, where they were given a final quality checkup.

Somewhere between 9:55 a.m. and 10:10 a.m. on 10 April, the F building was rocked by a violent explosion. As described in the next day’s New York Times, 18 tons of black gunpowder had ignited, setting off thousands of shrapnel shells and causing "a series of detonations that shook a half dozen boroughs within a radius of ten miles of the plant."

This was followed by a series of smaller, intermittent explosions and then a large one in a building filled with black powder. The shrapnel blasts injured not only workers but also many first responders, including a fireman who lost a leg to a bullet. The explosions killed at least 133 employees and severely injured, maimed and badly burned an additional 500. The majority of those killed were the women and young girls who worked in the loading room. “We had but a minute to reach the door,” a survivor told the Chester Times (now the Delaware County Daily Times) newspaper, “but many of us never got that far. Some were killed and others were injured by flying bullets.”

After an appeal for help was flashed, local residents rushed to the plant in cars and trucks to help transport the wounded to hospitals. Students from the Pennsylvania College arrived and proved helpful with crowd control. Numerous fire companies from Chester and Philadelphia raced to the scene.

|

| Post-Explosion Crowd |

All of the regional hospitals—Crozer, Chester, Taylor, and Media—were packed as doctors and nurses rushed to aid as many as they could. By 11 a.m., the hospitals were so full that the Chester Armory was converted into a temporary hospital, with Boy Scouts, National Guardsmen, and members of the Red Cross arranging cots in the drill hall. The Times described Chester Hospital as “corridors and side rooms lined with swathed forms, nothing visible of the person except for the tips of their noses. Intermittent screams of the suffering could be heard from the halls.”

Faces and bodies of the victims were blackened, as the powder had been blown into their flesh. Several bodies were discovered floating in the nearby Delaware River, where they either jumped to escape the fire and drowned or were blown into the river by the explosions. Many victims were identified only by their clothing, and at least 55 were never identified. Body parts were gathered and interred in a mass grave in the Chester Rural Cemetery.

|

| Preparing the Victims for Burial |

Some investigators suspected German saboteurs were behind the tragedy, since the plant had been supplying arms and ammunition to Germany’s enemy, Great Britain, and especially since the U.S. had only days earlier entered the war against Germany. Many (including plant employees) assumed that lack of appropriate safety standards at the plant was the actual cause of the disaster, but no real conclusions were ever reached.

While it today seems unbelievable, less than two weeks after the tragedy, the Eddystone munitions plant was reopened, and over 900 girls had reportedly applied to work there. Girls with German backgrounds were not hired. Today, the victims of the 1917 explosion are considered by many historians to be among the very first American casualties of World War I.

Sources: Phillyburbs.com; ABC Channel 27; WWI Centennial Commission; Wikipedia; Delco.Today; Timothy Hughes: Rare and Early Newspapers

The Eddystone munitions disaster on April 10th is a significant part of American History because it shows the vulnerability that Americans had to experience during periods of conflict due to corporate greed. The more ammunition companies produced the more money they made. Munition manufacturers had lucrative contracts with the allied powers producing millions of dollars. However, these munitions were at the expense of child laborers and women who had to provide for their families. Profits before safety. Munition manufacturers had inadequate safety measures that cost the lives of over a hundred women and children. In commerating the Eddystone disaster, we remember the importance of workplace safety and the women and children who sacrificed their lives to help win the war.

ReplyDelete