|

| Helmet of the 26th Yankee Division |

By Ben B. Fischer,

Originally Presented 12 June 2006 on HistoryNet

Part I

While scouting for the 26th "Yankee" Division during World War I, Sergeant James F. Carty and Private Harold F. Proctor eliminated a German position that had been holding up their comrades for five hours.

The Doughboy, not materiel, was the United States main contribution to Allied victory in World War I. General John J. Pershing believed that with equal training the American soldier would prove superior to his European counterpart.His hyperbole was not without some foundation. High literacy and mathematical abilities, combined with high morale, made the doughboys quick to train, though not always easy to command. The Americans fought well, and some, like Sergeant Alvin C. York, whom Pershing called the war’s greatest civilian soldier, became national heroes.

Among the citizen soldiers who formed the backbone of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was Sergeant James Francis Carty. Shortly before he died, Carty wrote an account of what he had done "over ther" during World War I. Titled "Hände Hoch!" ("Hands Up!"), his narrative vividly described how he and a comrade, Private Harold F. Proctor, captured a German machine gun nest and 41 prisoners in Bois de St. Rémy in September 1918.

Thousands of young men like Carty rushed to join the National Guard when America declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. They knew the Guard would be rapidly mobilized, federalized and dispatched to Europe. The Regular Army was too small to do the job, and the new conscript army was just getting organized. Carty, like a good many of his countrymen, objected to the new draft law and told his mother that "it would be better to enlist than be drafted."

When Carty enlisted, he was a state militiaman in a tradition-rich Connecticut infantry company. By the time he embarked for France, he was part of a new national army, a soldier in the 102nd Infantry Regiment of the 26th Division, better known as the "Yankee" Division because most of its troops came from New England states. The shotgun marriage of the National Guard and the Regular Army was never an easy one. The 26th Division’s most demoralizing moment came amid the agonizing Argonne campaign in October 1918, when Pershing sacked its beloved commander, Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Edwards, even though he was a fellow West Pointer. The Yankees never forgave and never forgot.

Rivalry continued to reverberate after the war, when the New Englanders—blessed perhaps with more than their fair share of intellectuals—produced three official histories and countless memoirs that defended their record, while casting aspersions on Pershing and his senior command. If the division did not win all its battles, it could at least note with pride that it was the first division to reach France intact, the first to go into the line as a division and the first to engage in a strictly German-American fight. The 26th also was in combat longer than any other division in the AEF.

Carty led the division’s observation group. Forward observation—critical at a time when communications technology was still primitive and tactical control often problematic—was dangerous work. Only nine of the 16 original members of Carty’s group survived the first month of combat.

Carty was better than most at his job. He had learned to hunt, trap and reconnoiter in the Canadian wilderness and had spent several years in the merchant marine. One of many commendations he received from the division’s G-2 (Intelligence section) began: "Your work as a member of the Division Observation Group and later as Group Commander was, I believe, unequaled by any man in the other divisions of our army." Even Pershing and his headquarters staff, whose praise for the controversial Yankees was sparse, considered the 26th’s observation group the best in the AEF.

|

| Orange Shading Shows Advance of 26th Division Towards Hattonchatel; Wedge Shape Shows Location of Bois de St. Rémy |

The St. Mihiel offensive’s objective was to reduce the large German salient protruding from St. Mihiel, and the 26th played a major part in the secondary attack on the northern flank of the salient. The division was to drive from Mouilly toward the towns of Hattonchâtel and Vigneulles, then link up with the 1st Division, coming from the south.

Carty was one of the first observers to recognize and report that German Army Group C was already making an orderly withdrawal, contrary to intelligence assessments. He also reported that the Germans in his sector, close to their base and determined to protect a vital supply route, were well positioned to wage a rear-guard action. In the following excerpt from "Hände Hoch!" Carty recounts his experiences on the first day of the St. Mihiel offensive:

"It was on the 3rd of September, 1918 that the General Staff of the Yankee Division decided to give me an opportunity to demonstrate some new ideas in regard to the functioning of the Intelligence Service during attack. For this purpose, I was called from my duties with the Battalion Intelligence Section and given a picked body of men and unlimited power to carry out the theories which previous experience on other fronts, and especially at Château-Thierry [in July 1918], had convinced me were right. In previous engagements, unexpected changes in both our own positions and those of the enemy had been noticed and foreseen, which, if taken advantage of at the right time, could have hastened our progress, killed more of the enemy, and saved the lives of many of our own men. For instance — after the enemy’s front line had been broken, it was to his advantage to resist at the points which gave him the greatest natural protection, and those points could be determined beforehand by a study of the terrain.

"A better system of applying tactics on the field was needed — a much better system. The tactical brains of the Division were in division headquarters, at least four kilometers from the front. The plans for attack were made there. The information from the lines was received there through long channels, and there were longer intervals between the times absolutely dependable information was received as to positions of units in our own front and a correct diagnosis of the enemy’s movement. The General Staff must become more intimately acquainted with events as they occurred on both sides of the line, and they also would have to shoulder the responsibility for a greater part of the minor tactics, as well as making the plans for the general attack. I firmly believed that the only way for them to gain this more intimate knowledge of conditions was through a group of men who would accompany attacks, at various points in the line, and do nothing but keep the Staff supplied with the information which they needed.

"By September 7 we were on our way, by short night marches from one patch of woods to another, to take our position for the St. Mihiel Drive, which was about due. Our Headquarters was already established on the extreme left of the American forces, not far from Mouilly. We were to capture the sharp ridges which extended fourteen kilometers southeast from Mouilly to Hatton-Châtel. Under the direction of the assistant chief of staff [Lt. Col. Hamilton R. Horsey], I made very careful plans covering the entire division front, and for conveying back the information we secured by telephone, being given additional signal corps men for that sole object. Every available map of the terrain was studied, and from the Mayor of Pierrefitte, we secured a large scale map of Hatton-Châtel, the town we were to capture at the end of our objective. Every elevation and the ground formation which could be seen from it, was plotted on our maps, together with the time at which our barrage was scheduled to rise from those points.

|

| These Former French Trenches Were the Jump-Off Line for the Yanks |

"At midnight on the 11th of September, the best barrage which we ever had roared out its opening chorus and at seven o’clock the following morning, with the barrage still pounding unmercifully, we got ready to start. The twisted pair, or ordinary telephone line which we had been using up to that time, was disconnected, as from then on, we were to rely on a single wire and the use of the ground. In this way a connection can be made at any point by jabbing a trench knife into the ground and connecting one pole of the field telephone to that. At eight o’clock the barrage lifted, and we went over the top with the Infantry. The enemy’s trenches were about four hundred yards away near the top of the next ridge. The ground between was terribly mangled by artillery fire, masses of tangled barb wire, and blasted trees laying in all directions, but nevertheless the Infantry went down our side of the valley and up the other side with good formation and with few losses. My men followed me in single file, the signal corps men unreeling their light wire as they went. The Boche [a derogatory French slang term for Germans, adopted by the Americans] first line, although composed of stone and concrete trenches, was completely wrecked by our artillery. We followed our barrage so closely that we caught most of them in their dugouts, and those who did come out to fight were quickly bayoneted or made prisoners. Their first line was captured in less time than we had expected, and within twenty minutes the General Staff was aware of the fact. When we reached their second line of resistance, there was a dense undergrowth which afforded them better cover, and, as the trenches were not so badly injured as was their first line, it took us a bit longer to mop up and get them all out. Our men were in an ugly humor that morning and worked with grim satisfaction.

"The possession of the second trench gave us high ground from which we could see to the next ridge about one and one-half kilometers further east, so we halted for a short rest while I plotted our position and sketched a rough map of the next ridge where we expected to meet with heavy resistance. We then filled our pipes and started forward again, for the Engineers were putting up a smoke screen to assist in the capture of the next ridge, and we could no longer see what was going on up forward. Upon catching up with the attacking wave, we found that they were meeting with heavy resistance. We got one call through and then our telephone went dead, for by this time it had become thoroughly watersoaked by the rain and short-circuited. With the help of the smoke screen and some nasty bayonet work, we captured the third line of resistance.

"The enemy had occupied another strong point in the woods bordering the Vaux-St. Rémy Road and kept a withering machine-gun fire on the road itself, which completely held up our advance and made re-organization extremely difficult and hazardous. I sent one man back to the point where we had left our double telephone wire with a message giving the approximate location of the enemy’s stronghold and stating the condition of our own unit. By this time, from the general trend of developments — the stubborn machine-gun fire, the absence of much enemy artillery fire, and the fact that enemy machine gunners had been hiding and opening up on our rear — all these facts made it plain that a general retreat was being covered.

"It was time to act and to act quickly. The unforeseen crisis for which my group was formed had arrived. The General Staff must know the extent of the enemy’s retreat. It was vital information. It was up to us to find out, and I had only one man left — Proctor. Could it be done? Unless it could, we would fail miserably in our duty. I hated to order Proctor to go with me and I did not want to ask him for it seemed like certain death for us both. Still I knew he wanted to go so I said: ‘Proc, old man, are you with me?’ ‘You’re damned right!’ was the answer, although he looked a little more serious than usual, and added as an afterthought: ‘I think you’re foolish though.’ And then good old Proc looked at me with a twinkle in his eye and said: ‘Jim, you’re the biggest damn fool ever turned loose in this AEF — when do we start?’

"We threw away all our equipment except our pistols, gas masks, and a small pair of glasses and started to wriggle through the brush away from the road and toward the enemy. Taking advantage of every possible bit of cover that the ground or woods afforded and keeping a sharp lookout for Boche, we moved rapidly on. Soon we could see small groups of Germans and looked about for a chance to penetrate their lines. Luck was with us.

"Apparently their rear area was deserted, and we hiked forward with comparative safety, avoiding a few of the enemy whom we saw first. A half kilometer more and we were so certain of our safety that we filled our pipes and thoroughly inspected barracks and dugouts to a depth of two kilometers, all of which we found deserted except for an occasional straggler whom we avoided, as we could not accomplish our purpose by fighting. We had obtained our information. One of us must get back with it. We had obtained it without fighting, but the chances of getting back without fighting were not so good, for it is less difficult to approach an enemy without being seen than it is to leave one behind.

|

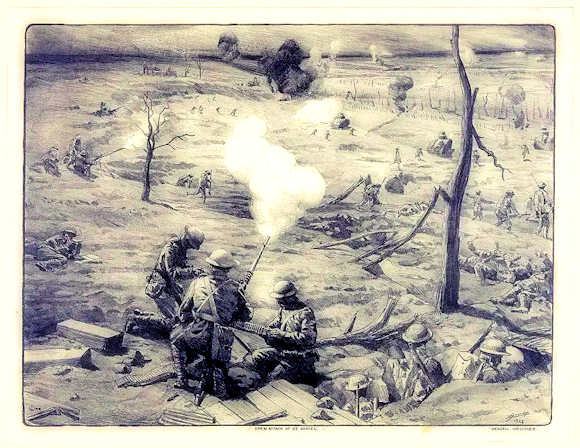

| French Artist Lucien Jonas' Depiction of the American Attack at St. Mihiel |

"We crossed the Grande Tranchée and decided to explore the woods to the southwest on our way back. Everywhere we went there were signs of abandonment. When about halfway back, we came upon a newly laid telephone cable which we decided to follow. It led us through some terribly rough country, and by following it half a kilometer we reached the crest of hill 380. From this point, much to our surprise, we could see quite clearly one of the enemy machine-gun nests which was holding up our advance. It was on the second ridge from us but the ridge in between was a bit lower in that line of direction and we were able to see about twenty of the enemy, working their machine guns, carrying ammunition, and the like. We were pretty sure that the telephone cable led to that nest, so we decided to cut it. However, it was about half an inch thick, and we had no tools so were stuck for a moment.

'Bite it in two,’ suggested Proc with a pleasant smile. Now Proc had a way of smiling that would make anyone mad, so I got mad and three shots from my forty-five quickly parted it.

'Now you take a bite,’ I said, ‘it’s your turn,’ and we moved over into the bushes and sat down to talk things over.

'Well!’ said Proc, a bit sarcastically, ‘how are you going to get by those Dutchmen?’

'I’m not going to bite my way through,’ I told him.

'No,’ he said, ‘I suppose you will light your pipe and put up a smoke screen.’ Evidently, Proc was a bit nervous and I was a bit peeved at his last few remarks.

'That was a bright idea of yours,’ I said, ‘that one about the smoke screen,’ and I fished out the old briar stove for another smoke.

'Why don’t you advertise in the paper that we’re here?’ was his next little pleasantry, as he watched the cloud of smoke that went up from my pipe.

'Now listen Proc. I believe we can get back to our own line and take those fifteen or twenty Boche with us,’ I said, trying to get his mind back to business, but Proc was hopeless.

'I won’t go near that bunch without a proper introduction,’ said he. ‘There are too damned many of them. Our report would go to Berlin instead of to the old Y.D.’

"I was very serious, however, and, as I told Proc, the nature of the ground and the fact that we were in their rear would allow us to get right among them before we were discovered. If we worked quick, and they acted as they usually did when surprised, we would have them disarmed before they really knew what had happened, or, if they showed fight, I had two automatic pistols and Proc one. Even if they killed us both, we could make it awfully costly for them for at close range the forty-five is the most deadly weapon made."

Part II will be presented tomorrow on Roads to the Great War