On 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany.. and "her

large Fleets vanished into the mists at one end of the island. "Rarely,"

wrote Arthur Marder, "had a fleet so itched for action or had so much confidence

in the outcome." On the opposite side of the North Sea, the High Sea Fleet

too waited for der Tag, convinced that "the English Navy would immediately

take the offensive." Both fleets were confident that the titanic clash would

take place in the first weeks of the war. After all, everyone expected the conflict

to be short, and both navies were imbued with "a healthy contempt for the

defensive." Few planners on either side seem to have given much thought as

to how they would reap the strategic benefits of a victorious new Trafalgar.

Click on Image to Expand

High Seas Fleet on Prewar Maneuvers

Prewar Expectations of a North Sea Trafalgar

It is difficult to conclude that, for all the mental and material preparations

that went into the prospect of a North Sea Trafalgar, much systemic thought

was given to how success on a Nelsonic scale was to be exploited. The theory

of the decisive battle offered a number of possibilities. First, a great fleet action,

ideally coinciding with a victorious battle on land, might ensure the short war

that everyone expected. Both navies toyed with this hope early in the war, but

it soon became evident that the opposing armies had settled down in the trenches

for the duration and were not likely to be dislodged by a big battle at sea. In any

case, neither side had given much thought on how decisive fleet action would

support the armies' strategies on land. This lack of "jointness" cut the other

way as well.

Neither the British nor the German army war planners seem to

have considered whether and how naval battle might contribute to their goals

on land. The British general staff was interested in the navy's plans mainly to make sure that its expeditionary divisions would get across the Channel

safely. Its German counterpart was even less interested. It thought that naval

interference with the British cross-Channel expedition would be helpful, but

not necessary. When the navy's chief of staff, Vice Admiral Baudission, asked von Moltke in 1908 whether the army preferred that the fleet not be initially

involved in a decisive battle, he was told that the army had no objections to the

fleet's full involvement and that it "would happily greet any tactical success

that the fleet would have."

| Read Jan Breemer's ground breaking work on how the Convoy system developed to deal with the U-boat menace in WWI.

|

Order Now

|

If battle at sea alone could not end the war, successful fleet action might still

"enable" victory by securing the sea for an invasion of the opponent's homeland

and, alternatively, against a counter-invasion. Both sides, Britain more so

than Germany, contemplated "peripheral strategies" against the opponent's

homeland, and both reckoned with the possibility of an enemy seaborne assault.

Even so, few naval and military planners on either side thought the prospect of

an invasion so menacing that a decisive sea battle was called for. None of

the various schemes that Churchill and others put together before and during

the war for launching a naval offensive in the Baltic was contingent on wiping

out the High Seas Fleet first. The reason why one or the other, Frisian Islands or

the Pomeranian coast, were never invaded had nothing to do with the continued

existence of the German battleships, but everything to do with the realization

that the would-be invaders would not be able to maintain themselves once they

had landed.

On the more practical side of war planning, the British Admiralty reiterated

the "paramount value of the quick decision" on the grounds that, with command

of the sea in hand, cruisers could then be dispatched to hunt down the enemy's

remaining commerce raiders. The argument that the big battle would ensure

the safety of one's shipping rang "strategic" enough but ignored historical

experience, including the aftermath of Trafalgar itself — big fleet engagements

have rarely solved the safety of shipping.

Click on Image to Expand

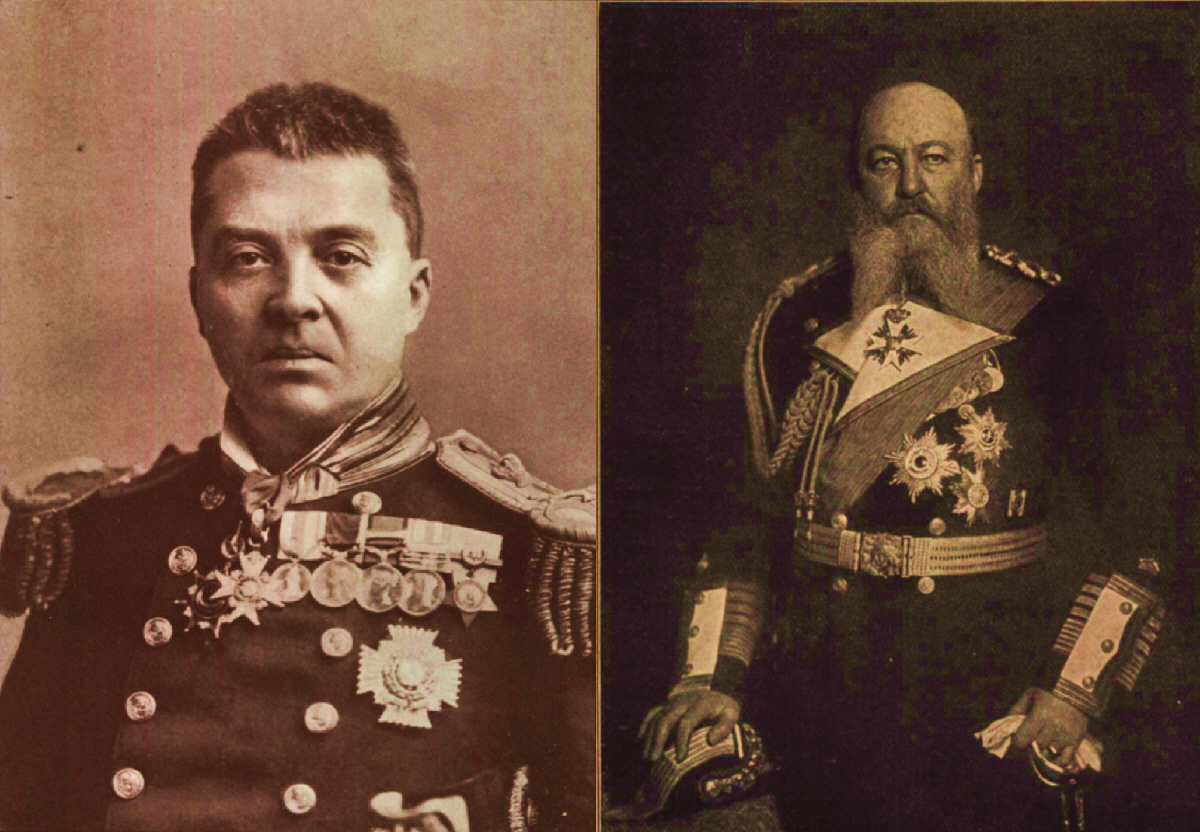

Fisher and Tirpitz

The Two Dominant Admirals and Naval Thinkers Before the War

It is a curious paradox that Admiralty planners thought a decisive battle

desirable for the sake of the safety of shipping and yet insisted that the threat to commerce would be minor compared with the depredations of Napoleon's

privateers. Corbett, who was more aware of the linkage between naval strategy

and commerce protection than most of his contemporaries, thought that "so far

as it is possible to penetrate the mists which veil the future," the prospects for

commerce destroyers making "any adequate percentage impression" were "less

promising than ever." Tirpitz agreed, rejecting attack against trade as the

High Seas Fleet's goal.

It can be protested that Corbett, Tirpitz, and the naval profession were right;

cruiser warfare on the surface would have inflicted little injury, and no one

could have anticipated the havoc wrought by the U-boats. The argument

misses the point, however. How could another Trafalgar be promoted as

decisive for the safety of shipping when the anticipated losses before the battle

were not a major concern. If the loss of merchant shipping while command was

still in "dispute" amounted to no more than "breaking eggs" while the fleet

waited to fry its "omelette," then why have an omelette at all, especially since the

war was not supposed to last more than a few months?

Click on Image to Expand

Royal Navy Battlecruisers at Sea

A final observation concerns the Admiralty's ambiguous connection between

the tactical means of fleet battle and the strategic objective of the safety

of the sea lines of communications. This is that, when all was said and done,

the strategy of sea warfare took a back seat to the strategy of battle. The upshot

was that the protection of commerce was effectively treated as a "necessary

evil" that could not be allowed to interfere with the "practical" business of battle

but that yet needed to be put forward as the "national" reason for decisive battle.

The irony is that the Admiralty and its supporters in the press made no effort

to hide the priority of the Navy 's goal over the nation's. The Royal commission

report of 1905 on the Navy's readiness to safeguard the arrival of enough

foodstuffs [is revealing] —"popular pressure, exercised through Parliament

upon the Government" could not be allowed to interfere with the Navy's

concentration for battle. The Admiralty's pen-writing supporters joined in. The

"defence of commerce," wrote Thursfield in Brassey's Naval Annual in 1906,

"is merely a secondary object" that "must not in any way or to any degree" be

permitted to take precedence over the "primary object" of command of the

sea. If the safety of seagoing traffic was not the fleet's and battle's first

purpose, then what was it?

The gap between strategic purpose and battle planning was even wider in the

German Navy. Before the war the German Navy formulated a series of

ambitious plans for fighting an offensive Entscheidungschlacht on the high

seas. They contained a great deal of discussion about the operational "necessity" for such a battle, but at no point was it made clear what the outcome was

expected to deliver other than a great deal of carnage. But then, the High Seas Fleet was built for "luxury." It was a fleet with all the material qualifications

for battle but without a reason other than the vague notion that it would,

somehow, bring Weltmacht. Had the High Seas Fleet fought and won its big

battle, it is doubtful that it would have known what to do with the results.

Excerpted from:

Naval Paper #6, The Burden of Trafalgar: Decisive Battle and Naval Strategic Expectations on the Eve of the First World War by Jan S. Breemer