The Photographic Archive of Dr. Giulio Andreini

and How I Came to Own It

By Doug Frank

Click on Image to Expand

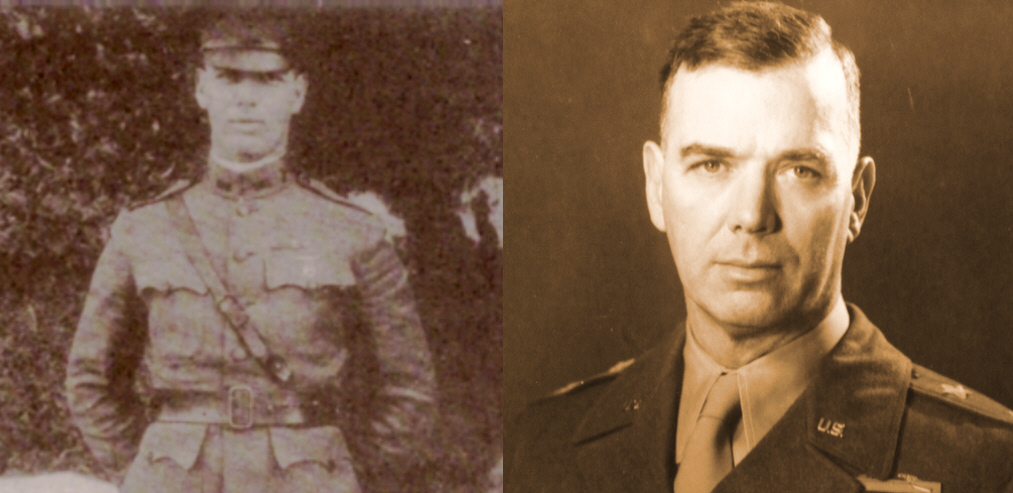

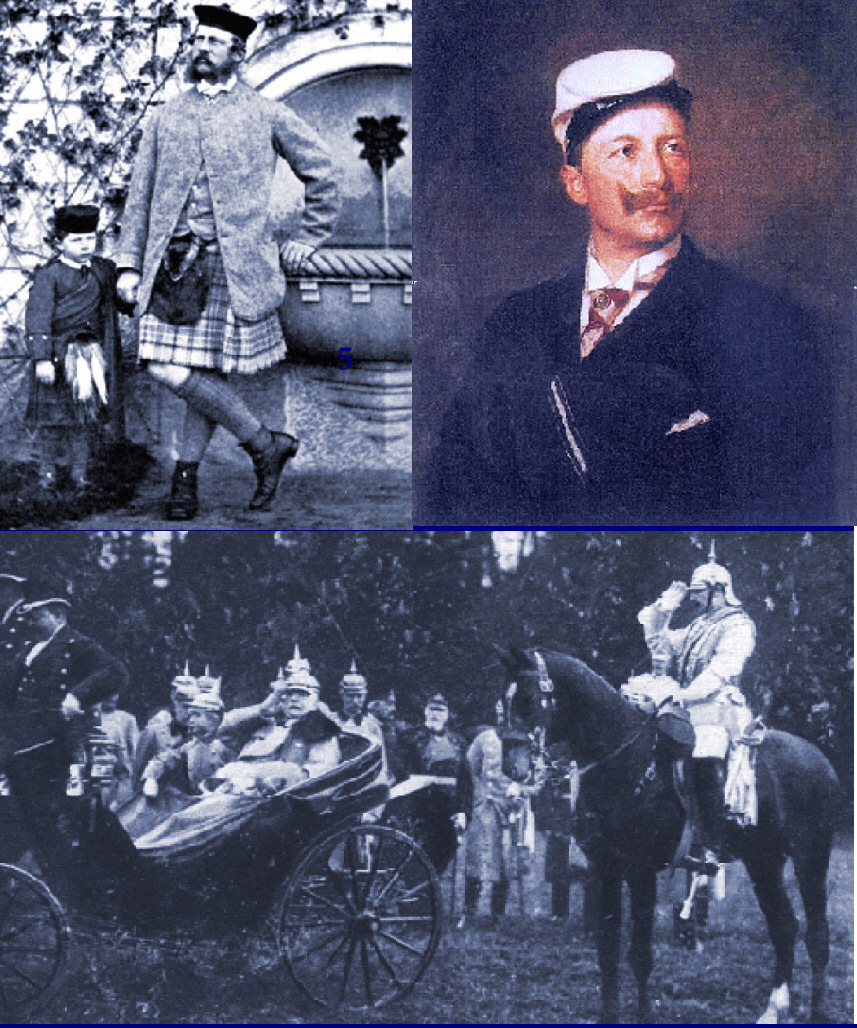

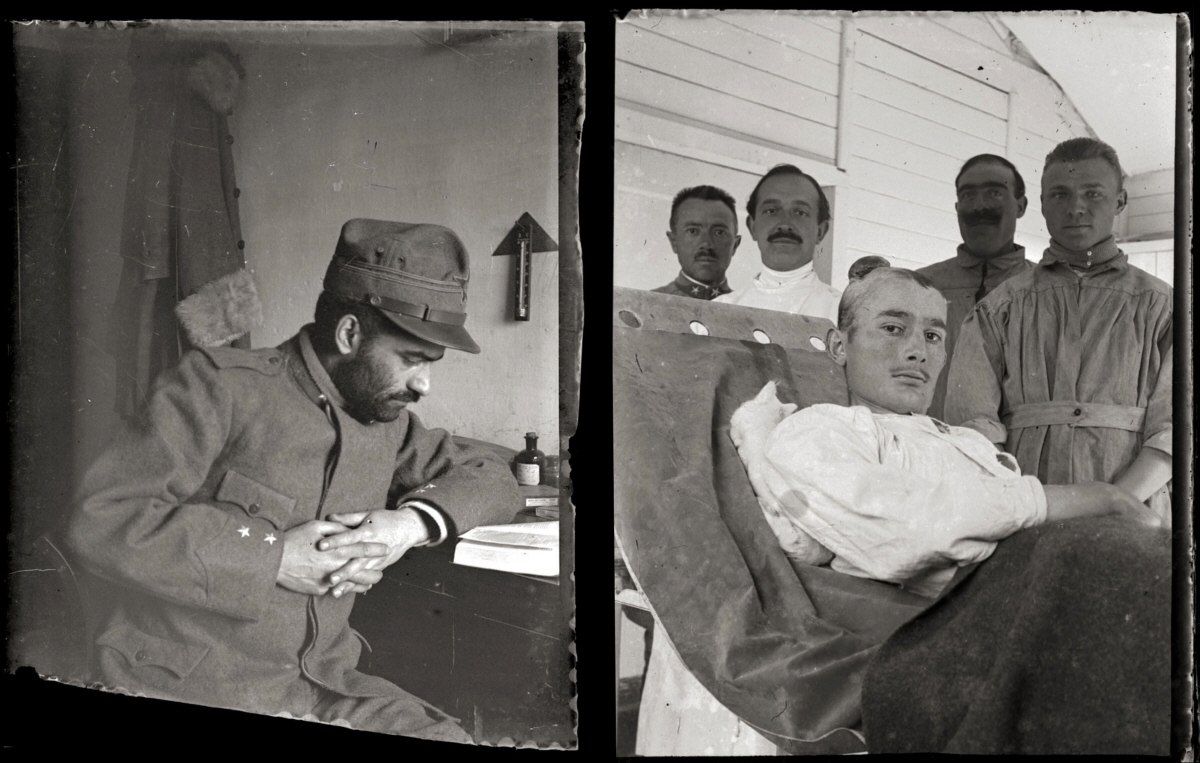

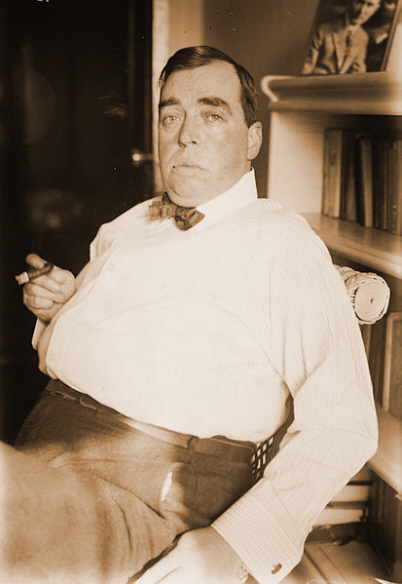

Dr. Andreini, Left, and a Recovering Patient

[Editor's note: Collectors are a big part of the World War I community. They help keep interest in the war alive and preserve its heritage. On 26 July we presented some of the photos of the Italian Front from Dr. Andreini's collection. The response from our readers was very positive and I thought some more photos from the collection, and Doug Frank's story of how he came into possession of it would make a fine article. So here it is. MH]

Photographic negatives made on glass plates always have been a fascination of mine. The often uneven edges of a glass plate seem to give me the sense that the image actually is emerging from the blackness of time past — a true artifact. I began collecting a varied group of such plates many years ago. eBay has been my primary source, although wherever I come across one of these I look at it very carefully. The majority of my glass plate collection was made by anonymous photographers. The human subjects, too, are mostly anonymous and long dead.

I am a career photographer and am quite familiar with the use of high-end scanners as well as various types of image editing software. Film has always been my number one medium, although digital cameras have become a necessity to me in recent years. In 2004, I came upon an auction on eBay for several vintage glass negatives of a medical nature. There were two that caught my eye. One was a 9cm x 12cm portrait of a nurse, and the other was a 13cm x 18cm negative of a medical procedure involving a woman and four doctors. I came to own both of these photographs after winning the two auctions.

Click on Image to Expand

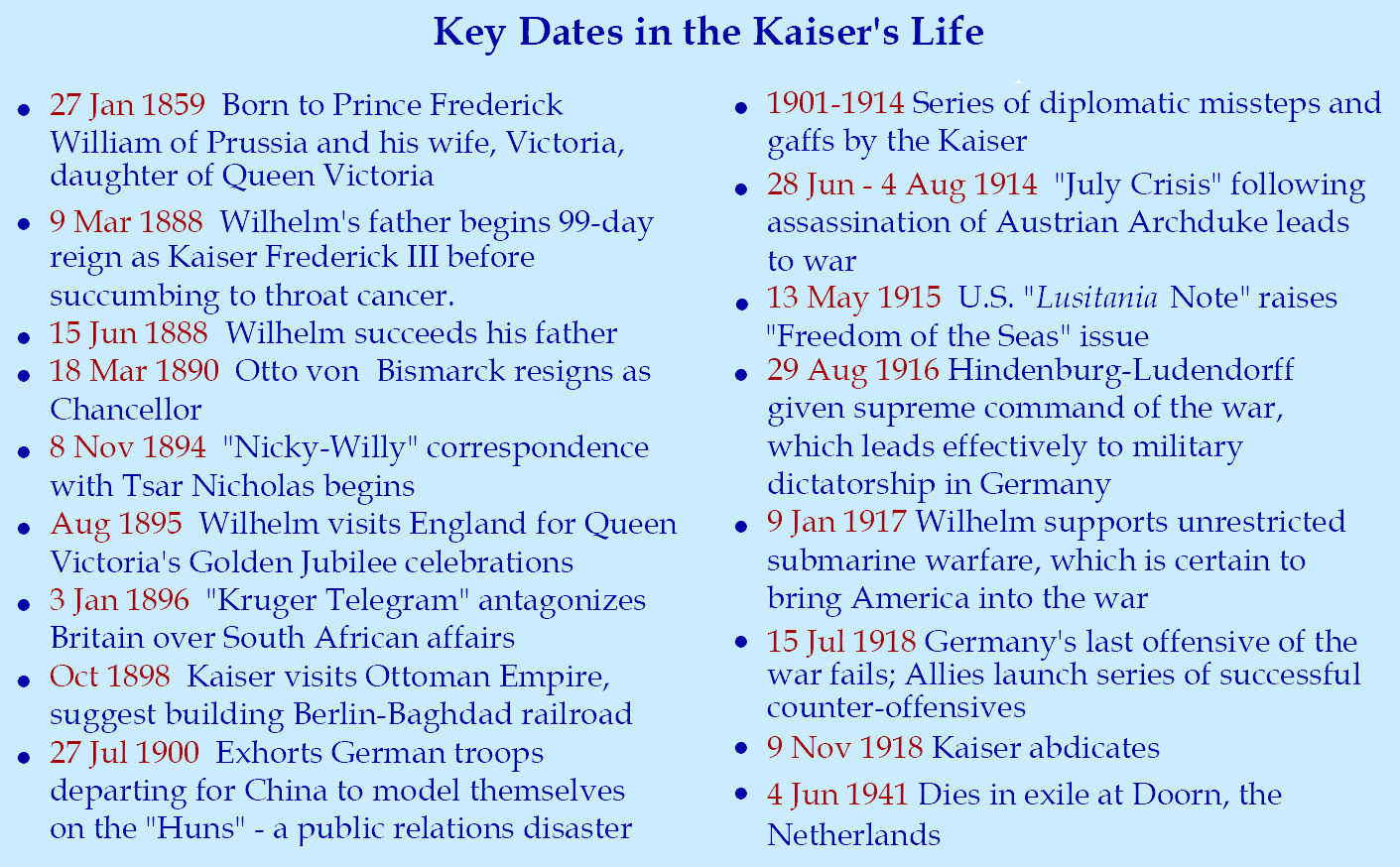

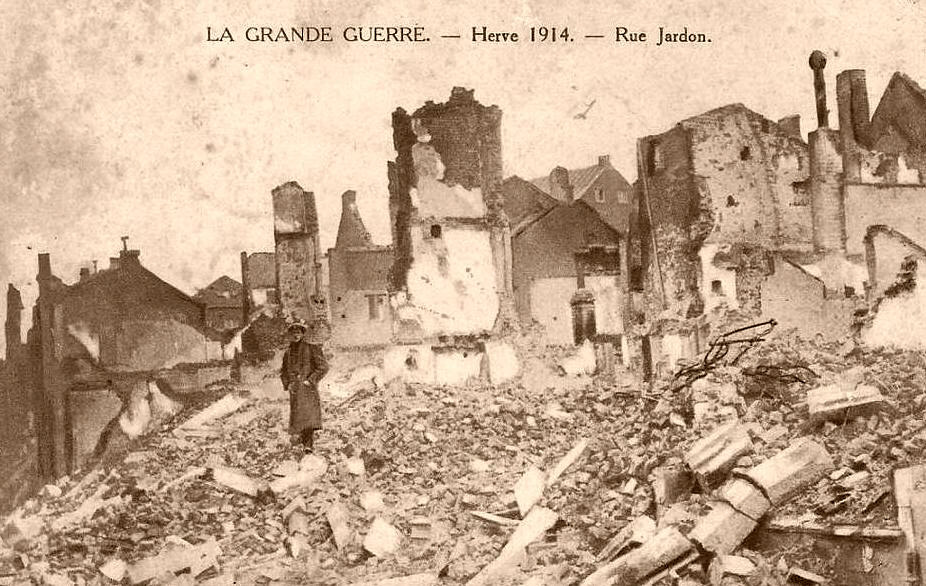

Classic World War I Pose

A few weeks after this sale, I received an e-mail from the dealer who had sold me these plates. He was located in Los Angeles. He explained that he had come upon the archive of an Italian physician named Giulio Andreini, who lived his adult life during the first third of the twentieth century. The dealer had found this archive in Lucca, Italy, and purchased the entire collection from an antiquarian there. However, he went on to say that he had only been interested in negatives of a medical nature, although he was obliged by the antiquarian to purchase the entire archive in order to obtain the images that he wanted. In fact, he still owned about 1,400 glass plates made by this physician but had sold the ones he wanted to sell and had no further interest in the remaining archive, so he asked me if I would like to purchase all 1,400 for $500.

From his description, there were about 250 small glass plates of WWI. The rest appeared to be family photographs, portraits, and others made in hospitals. I went ahead with the purchase. The sizes of the plates range from 4.5cm x 6cm to 18cm x 24cm. The majority measured 4.5cm x 6cm, and virtually all of the war photographs were made in this format. There is one interesting aspect about the WWI plates. Many have very jagged edges. My guess is that 9cm x 12cm plates were the most readily available, but Dr. Andreini’s camera used 4.5cm x 6cm plates, so he probably broke the 9 x 12 plates into quarters somehow, thus giving him the ability to use them in his small camera. This camera was a Contessa Nettel Duchessa, produced in Germany from 1913 to 1925. It was about the size of a modern 35mm camera and could be used either handheld or on a stand.

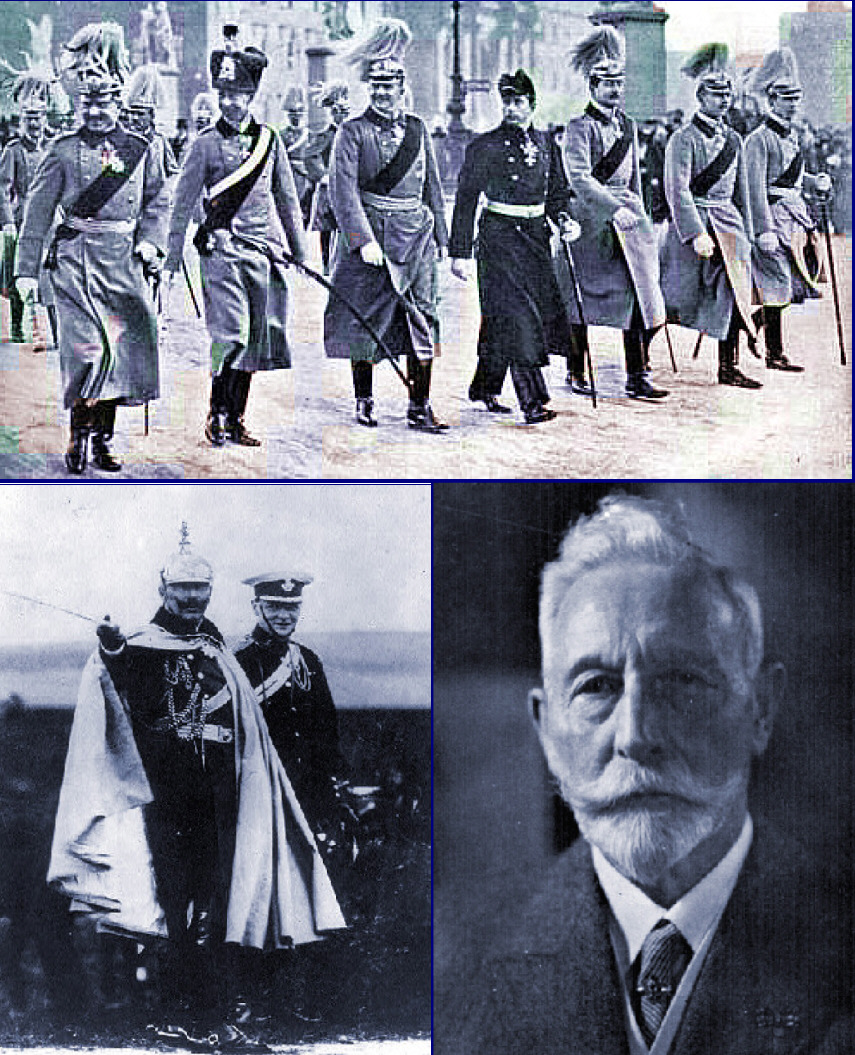

Click on Image to Expand

The Contessa Nettel Duchessa Camera

After receiving Dr. Andreini’s archive from Los Angeles, I did a quick survey of it, looking at every negative. My first conclusion was that this man was a superb amateur photographer. My second conclusion was that his WWI plates deserved to be seen by people other than just me.

I then attempted to find information on Dr. Andreini and if he had any relatives living. So I Googled “Giulio Andreini.” The first hit was the website of a “Giulio Andreini, Photojournalist, Siena, Italy.” When I opened the site there appeared a photograph of this Giulio, aged 44. I knew that I was on the right track. Dr. Andreini had made many self-portraits, and this man looked just like him! So I e-mailed the young Giulio and asked if he had a relative who had been a physician in Florence, Italy, in the early twentieth century as well as an amateur photographer. The e-mail I received back confirmed my suspicions.

Yes, he said, his grandfather was named Giulio Andreini, and, yes, he had been a physician as well as a photographer, but all of his work had been lost in 1937. This was the family lore as he knew it. In fact, the Andreini family possessed just a single photograph of the doctor! The young Giulio wondered, however, as to how in the world I could possibly be in the possession of any his grandfather’s photographic material. After all, I lived in Oregon, half a world away from where the photographs had last been seen, in Florence, in the doctor’s medical office there sixty years before. So I suggested to Giulio that I send him one of the self-portraits from the archive, and he then could confirm or not whether the man was, indeed, his grandfather. I sent the photograph and he responded with a resounding “YES!”

Please refer now to

Roads to the Great War and a post from Friday, 26 July 2013.

It contains a biography written about Dr. Andreini by his son, Giorgio. The last sentence of the biography refers to an episode described in my next paragraph. Giorgio has since passed away. Dr. Giulio Andreini passed away in 1937 from acute leukemia rather suddenly at the age of 49 years. After his death, his widow, Georgette, went to the hospital where he had worked, taking her thirteen-year-old son, Giorgio, along with her. She asked the nuns who ran the hospital if she could please collect all of her husband’s personal items, such as his photographic material as well as several books of poetry that he had written.

Click on Image to Expand

Helping a Dog Cross a Trench on the Asiago Plateau

One of the nuns informed Georgette that the hospital had destroyed everything of a personal nature that had belonged to him, presumably, and in her words “for the good of the family.” The ensuing conversation became quite intense according to Giorgio, but the nuns held firm. The photographs were gone. “For the good of the family” could have had any number of meanings, but I like to think that the nuns were trying to protect the Andreini family from possible repercussions from the dictatorial government in Italy during that time. This was, after all, 1937, and the fascists under Mussolini were running Italy. It is known that many of Dr. Andreini’s poems were satirical and critical of the government as well as the Catholic Church. This material, if seen by government officials, possibly could have presented the family with big problems.

I culled about 350 glass plates from the archive, mainly family pictures, and sent these as scans to the young Giulio. He went on to make prints of these images for all of his relatives and was able, with the help of his father, to reconstruct the history of the Andreini family. He has since even found a previously unknown branch of relatives in the Milan area and has made contact with them.

Click on Image to Expand

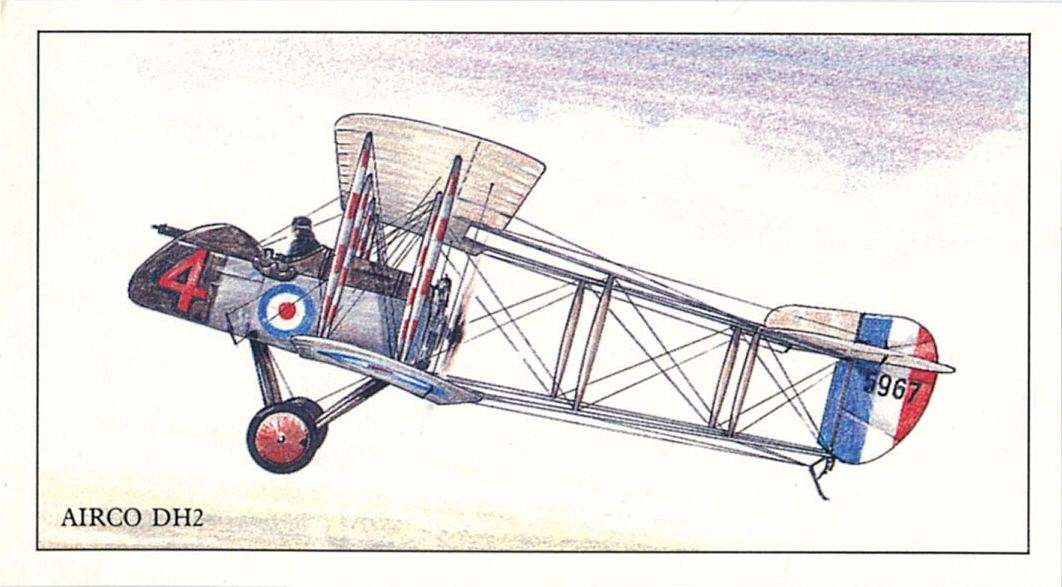

Two Towns: Unidentified Town on Italian Front, Left; Château-Thierry, Western Front

So the archive of Dr. Giulio Andreini had never been destroyed after all. It probably was sold or given away by the nuns to someone who kept it in a safe place, where it remained undisturbed for the next sixty years. It then resurfaced intact and fell into the hands of the antiquarian from Lucca, who sold it to a dealer in Los Angeles. Then I purchased it and still am holding all 1,400 of the glass plates. Although I own the publishing rights to this work, I am in the process of finding a permanent home for the archive. If possible, I would like this home to be in Italy. His poetry, however, remains lost. As a final note, the young Giulio and I have become good friends over the years. My wife and I visited him in Siena in 2006 and reconnected with him again this past June while we both were traveling in France.

Presented here is a second group of images for the readers of Roads to the Great War from his series on WWI, which he photographed while working at a field hospital on the Italian Front between 1915 and 1917. He had been transferred to the French Front when the war ended.

Doug Frank

Portland, Oregon

August 2013