|

| Hiram Maxim, Father of the Machine Gun |

The Development of the Machine Gun

and Its Impact on the Great War *

MAJOR JACK R. NOTHSTINE, U.S. Army

At the onset of the Great War, the tactics and strategies of all of the major powers did not take into account the

technological development of the weapons that were implemented. All of the major powers held firm to the belief

that the modern battlefield would allow militaries to maneuver and engage with tactics that had been used prior to

the implementation of one major innovation—the machine gun. The introduction of this weapon to the battlefield

allowed a concentration of firepower that changed the way war was fought and ultimately led to the establishment of

the trench system. The defensive power of the machine gun created the stalemate on the Western Front, and almost

all of the technologies that were introduced during the war were built in order to defeat it. The introduction of this

weapon radically changed the strategies and tactics used by militaries in the future.

The Franco-Prussian War and the Russo-Japanese War are the two most significant wars that influenced military

theorists prior to the Great War. These wars revealed the improvements made in artillery and small arms. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 demonstrated the impact of the machine gun and revealed two important lessons:

* First, that use of the machine gun in the defense resulted in the digging of trenches,

and

* Second, that machine guns could be used to decimate a far larger offensive force as was demonstrated by the

Japanese use of the Hotchkiss gun.

World militaries were not ignorant to these lessons, but they tended to view the battlefield developments as proof of

Russian military weakness and not the result of the inherent defensive power of the machine gun or the inevitability

of trench warfare.

Instead, the European militaries were influenced primarily by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. This war occurred

in Europe and had been won using classic maneuver and encirclement tactics. It became the archetype for all of the

European powers—particularly France and Germany—on how to conduct a successful military campaign. The

major powers of the Great War failed to understand that in the 43 years since the Franco-Prussian War, technology

had developed in such a way as to make previous tactics obsolete, as demonstrated in the Russo-Japanese War.

These militaries envisioned a highly mobile offensive as the key to success in future battles. France was soundly

defeated and humiliated at the Battle of Sedan (Franco-Prussian War, September 1870), and the provinces of Alsace

and Lorraine were annexed. “Joffre [commander of French military] was an ardent admirer of the all-out offensive, l’offensive à out-rance. He vowed never again to allow a French army to be encircled as at Sedan.”

It was from these origins that the spirit of the offense became the cornerstone of all the major powers’ military

strategies. Prior to the Great War, a Polish writer named Jean de Bloch wrote a book arguing that “the increased fire

power of infantry weapons would force troops to dig in for defense. Between the trenches a fire swept zone would

be created which could be crossed only at the cost of devastating losses.” Although his prediction turned out to be

remarkably accurate, the professional militaries of the time dismissed his claims, citing once again the importance of

troop morale and offensive spirit. History seems to judge France particularly harshly when regarding its reliance on

the offensive spirit (elàn). It is true that the French believed that it was the offensive spirit that would win battles, but

in reality all of the European powers were duped into the belief that the spirit of the infantry would be able to break

a fortified defense. They all believed it would be the power of their offense that would be decisive in future wars.

When the Great War began in 1914, the attacks were linear in nature and based on pre-war theories which didn’t

account for the machine gun. Each battalion advanced shoulder to shoulder with a screen of skirmishers out front.

Once the main force made contact with the enemy, reserves were fed into the battle in order to fill the gaps created

by casualties. The advancing force had two objectives: to suppress enemy fire and inflict sufficient causalities in order

to make the opposition waiver. Then, theoretically, once the enemy began to waiver, a bayonet charge would deliver

the final blow. “Victory would result, therefore, not from superior tactics, or even superior weaponry, but from the

imposition of superior will.” In reality, attacks very rarely ever culminated in a bayonet charge.

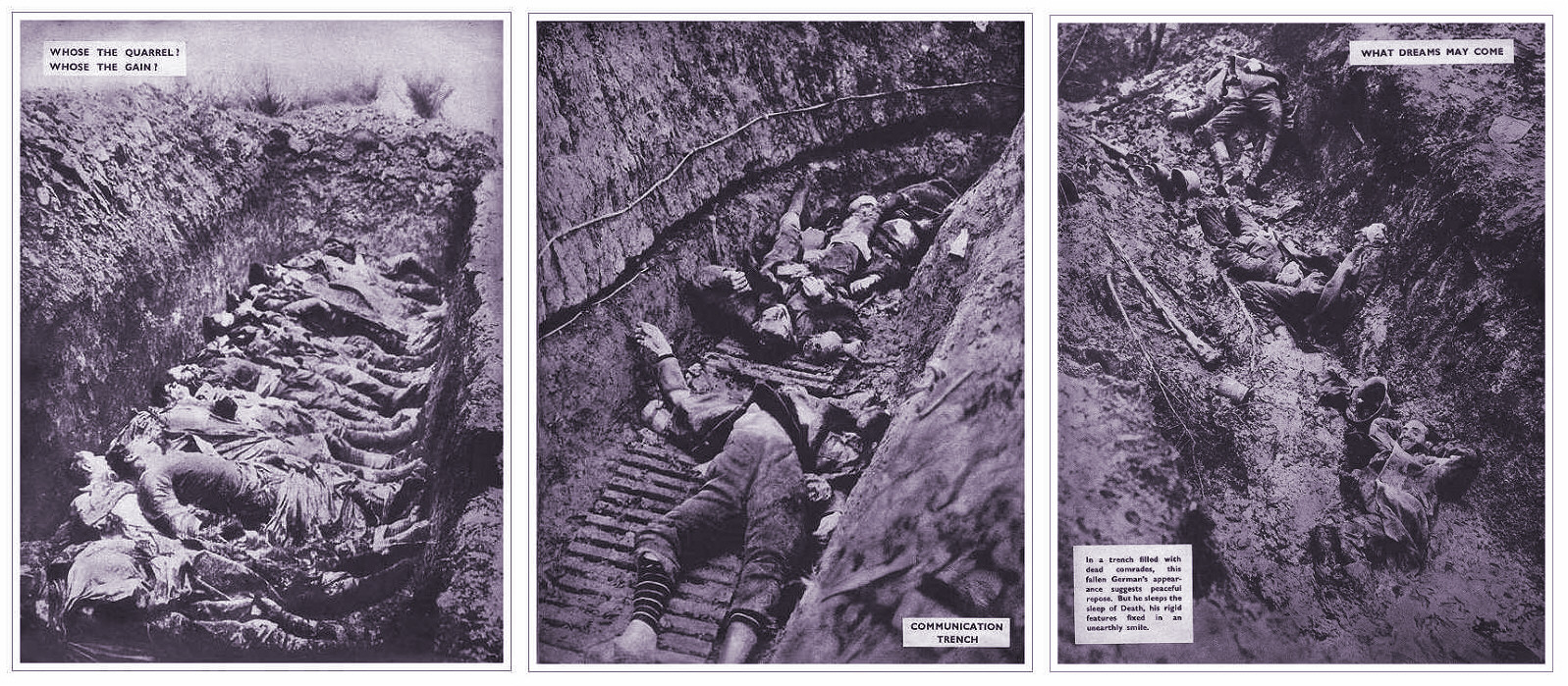

Much has been made of the battles of attrition, such as Passchendaele, Verdun, and on the Somme that occurred

later in the Great War. Often the initial battles, which were not fought from trenches, have been forgotten. The

impact of the machine gun was felt early on, and the result was the largest number of losses during the war. “The

enormous losses in August and September 1914 were never equaled at any other time, not even at Verdun: the

total number of French casualties (killed, wounded, or missing) was 329,000. At the height of Verdun, the three month period February to April 1916, French casualties were 111,000.” It was the impact and associated losses of

the machine gun that drove the major combatants into the trenches. The machine gun came to represent the use

of technology applied to weaponry. The power it gave to a single man made the offensive doctrine of the European

powers obsolete, forcing the armies on the Western Front into trenches. All of the combatants were left with the

option to dig in or be annihilated.

The primary reason the machine gun caused trench warfare was that the weapon was defensive. The Maxim and

Hotchkiss models were significantly smaller than previous models, but they were still heavy by modern standards.

The German Maxim 08 weighed between 136.4 and 146.3 pounds. and required at least six men to carry it and its

ammunition. The French and British machine guns of 1914 were not much better: the French Hotchkiss weighed

103.4 pounds and the British Vickers-Maxim 118.8 pounds. This meant that the machine gun could only be utilized

in a defensive role because it was far too heavy to incorporate in a highly mobile offensive manner. The results

were catastrophic and completely unforeseen by the military leadership. Sir John French, commander of the British

Expeditionary Force (BEF), captured the bewilderment of the now engaged European militaries when he said,

“I cannot help wondering why none of us realized what the modern rifle, the machine gun, motor traction, the

aeroplane, and wireless telegraphy would bring about.”

By 1915, a series of trenches stretched from the English Channel near Ostend to the northern border of Switzerland.

This situation would remain relatively unchanged until 1918. The Germans started 1915 with several major advantages.

Because they were occupying significant areas of France and Belgium, they did not face the same political pressures

to attack that the Allies had. The German army had chosen the areas for their trenches, and they naturally chose

terrain that favored the defense. This meant that the Germans were able to take a primarily defensive position in the

West, forcing the Allies to take an offensive strategy. The Germans also had a greater number of machine guns than

the Allies. “At the beginning of the war, the German army had more than 4,500 machine guns, compared with 2,500

for France and fewer than 500 in the British army.”

The Allies stuck to their now outdated doctrine and attempted a number of attacks by overwhelming forces against

the Germans with the hope that a combination of weight in numbers and offensive spirit would drive holes in the

German lines. They were a wholesale failure. The Allies demonstrated a complete inability to change their tactical

doctrine despite the unsuccessful nature of their repeated attacks. This lack of understanding was epitomized by

British commander-in-chief Sir Douglas Haig, who in 1915 asserted that the machine gun was “a much overrated

weapon.”

The German army would place their machine guns in such a manner that all areas of “no man’s land” were being

covered by the fire of multiple machine guns. This process of overlapping machine-gun fire was particularly successful

because it meant that if an individual machine gun was knocked out of action, the weapons to the right and left of it

could still cover all of the space between the trenches. It also meant that at all times the individual attacker was being

shot at from two separate locations. This made it very difficult for an offensive assault to achieve cover because the

enemy fire was coming from two separate directions. To further enhance the fire power of the machine gun, barbed

wire became a common feature in “no man’s land”. It was used by both sides in order to slow down an attack and

channelize the enemy into areas where they could easily be killed, called “kill zones.” At the Battle of the Somme,

one German soldier commented about how easy it was to defend against such an attack: “When the English started

to advance, we were very worried; they looked as if they must overrun our trenches. We were very surprised to see

them walking… When we started firing, we just had to load and reload. They went down in the hundreds. You didn’t

have to aim, we just fired into them.”

The attackers now had to run across open but uneven ground and cut through massive quantities of barbed wire

before reaching the enemy trenches, all the while under machine gun fire. Once the wire had been breached, the

attackers would naturally mass at the opening, thus presenting an even more attractive target to overlapping fire.

Expressing the feelings of a soldier facing masses of machine guns, French author Henri Barbusse described a French

platoon waiting to attack: “Each one knows that he is going to take his head, his chest, his belly, his whole body, and

all naked, up to the rifles pointed forward, to the shells, to the bomb piled and ready, and above all to the mechanical

and almost infallible machine guns.”

In an effort to break the deadlock, the British and French began to rely heavily on their superior supply of artillery

munitions. The concept was simple. They would bombard the German lines which would kill the front-line defenders

and destroy the barbed-wire obstacles. This would allow the Allies to move forward and seize the enemy trenches.

Artillery, as an indirect fire weapon, was still in its infancy, however, so it failed to achieve these two main objectives

and was therefore unable to overcome the supremacy of the machine gun. The process of aiming indirect artillery

fire (called registering) was notoriously inaccurate and unreliable. Even if the assault was successful, a dependency

on artillery made extensive gains impossible. The process for targeting artillery was time consuming. The artillery’s

reliance on registration meant that it was only effective to a range where targets could be accurately identified.

“Once beyond their original front line, the [attacking units] were no longer working from accurate maps and aerial

photographs. The enemy did not occupy such obvious positions, and many attacks came unstuck in hidden belts of

barbed wire or were decimated by previously concealed machine guns.”

Even when artillery was effective, it still failed in its two main objectives. Artillery failed to destroy the barbed wire

or sufficiently kill the defenders in the front-line trenches. Although they produced many casualties, they did not

result in significant gains. This was exemplified in the Battle of the Somme, which would later become iconic to the

British for the futility of the frontal assault. During this battle, the British falsely believed that they could overwhelm

the defensive might of the German trenches and machine guns with artillery alone. The tactic proved unsuccessful.

When the infantry began their attack, they found that the German wire was intact and the German trenches were

well defended. When the assault began, the Germans emerged from the bunkers, positioned their machine guns,

and proceeded to mow down the advancing British infantry. “No matter how heavily the artillery pounded the enemy

trenches, a few German machine guns survived and cut down thousands of attacking infantrymen. By 19 November,

when the offensive was called off, the deepest British penetration was seven miles from their starting point on 1 July.

They lost 419,654 men. The overwhelming majority of the dead fell to the machine gun.”

The deadlock caused by the machine gun gave birth to a number of new technologies. In April of 1915, the German

army first used chemical weapons—in the form of chlorine gas—at the Second Battle of Ypres. The gas was a

terrible new weapon, but ultimately it proved too uncontrollable to be used successfully. “The problem with releasing

gas from cylinders was that the wind had to be just right, lest the gas blow back into the [attackers'] own trench.”

The Great War also saw the first military use of the airplane. The airplane was used primarily as a reconnaissance

vehicle. When the war began, all of the aircraft were unarmed, but through the course of 1914, aircrews began to

carry revolvers and carbines in order to attack other enemy aircraft. In 1915, all the major combatant powers began

experimenting with machine-gun technology in the air.

In 1916, the tank first saw action during the Battle of the Somme. The tank appeared to offer the perfect solution to

the machine gun. The tanks deployed by the British came in two separate models: “the male version which included

six-pounder guns, and a female, which had only machine guns.” Later French and German tanks would also have

mounted machine guns. The presence of machine guns is very revealing. The tank was seen as a means of carrying

the power of the machine gun onto the offensive. It recognized that the best chance the infantry had of executing

successful offensive actions against machine guns was to use other machine guns. In the Great War, tanks suffered

from mechanical defects and were extremely slow (1.8 miles an hour on level terrain). For example, on 8 August

1916, the British began with “more than 450 [tanks] on the first day; there were about 150 left on the second day,

and 85 on the third.” Most of the tanks failed to even make it across “no man’s land.” The tank would ultimately

become a decisive weapon in World War II, but it would require years to improve the construction of the weapon

and perfect the tactics.

The most successful efforts to overcome the supremacy of the machine gun came not from technological advances

but from tactical changes. On the Western Front, the Germans had the advantage of being able to maintain the

defensive and as a result suffered fewer casualties than the Allies. The German army was more progressive in tactics,

having learned much by watching the continuous ineffectual results of Allied offensives. In 1915, “German divisions

got smaller; this was seen as proof that Germany was running out of men, but in terms of firepower—which was

the important measure—the divisions were becoming more and more powerful as machine guns replaced rifles.” More importantly, the German military began a long process of revising its tactical doctrine. The process would result

in the development of modern small unit tactics and offered the most successful countermeasure to the supremacy

of the machine gun.

Initially, the German military suffered the same fate as the Allies during offensive operations in 1915, but as opposed

to the Allies they recognized that they needed to address shortcomings in the way they conducted assaults. In

1915, the German General Staff began exploring several different approaches to combat, and they were able to

see marginal successes over the next few years because of their tactical refinements. German doctrine called for an

active defense, which meant that limited attacks should be made even while holding a defensive line. The Germans

created elite units called storm troops (Sturm Abteilungen)—“infantry able to mount countering attacks that would

throw the decimated attacking force back to its own line.” The storm troops were given greater ability to conduct

tactical experiments and develop offensive tactics. The result was a sharp contrast to the grand offensives launched

by the Allies. The Germans began operating in battalion or company-size elements using hand grenades as a primary

weapon (thus the origin of the word Panzergrenadier). The goal was to move with small units under the cover of

darkness or by using a short artillery barrage. German tactics worked because the Germans decentralized decision

making downward. In order to execute these actions, the soldiers had to be better trained and able to operate with

minimal leadership. The result was the formation of modern small unit tactics and the increased role of NCOs.

In combination with their decentralized tactics, the Germans employed sub-machine guns. In 1914, the Germans

began gathering the Danish Madsen and captured Lewis sub-machine guns from the British in 1916. These weapons

were distributed to storm troops and played an important role in German counterattacks at the Somme. After

the Somme the German army introduced its own light machine gun—the MG08/15. These were produced in

numbers significant enough for them to make an impact on Storm Troop tactics. “Fed by 100- or 200-round belts, the

MG08/1915 could provide much greater volume of fire than the Lewis or Chauchet light machine guns being used

by the Allies, and despite its weight (43 pounds), it anticipated the tactical role of the [machine gun] in World War

II.” Technical refinements to the sub-machine gun continued after the Great War and would ultimately result in the

creation of the assault rifle.

The Germans demonstrated their evolving small unit tactics during two large scale German offensives—Verdun

in 1916 and the Offensive of 1918. At Verdun, General von Falkenhayn engaged the French in a number of limited

engagements that were meant to take small amounts of land using storm troop tactics to limit casualties. Once

territory was gained in one area, the attack was shifted to another section. These small gains would add up to

significant territorial gains. French general Maurice Sarrail described the method as such: “They conquer parcels

of terrain where the loss or gain is of minimal importance, but their operations permit them to conserve moral

ascendancy.” The German objective was to seize Verdun and annihilate the French when they attempted to reclaim

it. “It was fundamental to his plan that the place chosen for attack should be, for whatever reason, an objective for

the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have.” In effect

once Verdun was captured using superior German tactics, then the French would destroy themselves against German

machine guns using inferior tactics. Though gains were made, the Germans failed to capture Verdun and endured

significant losses in the effort. The Germans often found themselves in the same predicament that the Allies had. At

Verdun, “one [French] section of two guns was isolated [and] held off the enemy for 10 days and nights, during which

the two guns are supposed to have fired in excess of 75,000 rounds.” But their tactics were marginally vindicated.

They suffered roughly an equal number of casualties as the French. But this was still a far better ratio then the Allies’

offensives against the Germans, where they often suffered eight times the number of casualties as the defender.

The Germans came very close to victory using decentralized tactics in the 1918 offensive. With victory in the east

over Russia, the Germans found themselves with a numerical superiority on the Western Front. The strength of

their position was only temporary as the U.S. was now entering the war, and the Allies would soon (and once again)

outnumber the Germans. In March 1918, the Germans gambled on one last offensive in an effort to win the war—the Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle). Unlike all of the previous failed Allied assaults against the German trenches, the

Germans would achieve a significant territorial gain. “By the time the Storm Troops led the great German offensive

of March 1918, German infantry tactics had changed beyond recognition.” The tactics of the Storm Troops were

continually being refined and disseminated throughout the army. “The Landwehr troops learned to fight in platoons

and sections, rather then lining up each rifle company in a traditional skirmish line. [sic] For the first time, NCOs found

themselves given a real job of leadership—making their own tactical decisions.” The change placed an emphasis on

short artillery bombardments (Sturmreifschiessen), the empowerment of small unit leaders, and by passing strong

points such as the machine-gun positions. The policy of bypassing strong points would be further refined after the

Great War and would become the foundation of blitzkrieg (lightning war) tactics of World War II. The result was an

overall improvement of the entire German army’s ability to defeat the machine gun’s domination of the battlefield.

The success of these tactics was remarkable. On the first day alone, German forces took about 98.5 square miles

of territory, “which was about the total amount of German-held territory re-conquered by the British during the

whole of the 140 days of the Somme offensive in 1916.” Ultimately, the German’s tactical refinements came too

late. Despite their success after one week, the German army was unable to advance farther. They had achieved the

greatest gains in territory since the stalemate began in late 1914. But in doing so, they incurred 239,000 casualties

during the advance while the newly arriving American numbers in May rose from 430,000 to 650,000. The gamble

had been lost, and the German government realized that defeat was inevitable. There is a certain amount of irony

in the fact that it was the German army that found the key to the breakthrough, but they would ultimately lose the

Great War.

There were a number of technological advances introduced during the Great War, but the machine gun was the most

decisive. WWI European powers failed to recognize how the machine gun would impact their tactics; they all believed

it would be the power of the offense that would be decisive in future wars. They were proved wrong in numerous

battles which resulted in significant loss of life for minimal territorial gains. Ultimately, it was the implementation

of small unit tactics developed by the Germans—not the grand offensives of the Allies—that provided the best

solution. The machine gun was the decisive weapon of the Great War, and its introduction to the battlefield would

radically change the strategies and tactics used by militaries in the future.

*The views expressed here are those of the author and are not necessarily agreed with by the editors.

Source: Infantry Online, January-March, 2016