THE WAR THAT ENDED PEACE: The Road to 1914

World War I is often depicted as a tragic accident in which the assassination of an Austrian Archduke by Serbian nationalists sets in motion a string of falling dominos that brings the old European civilization crashing down. The War That Ended Peace shows that there was much more to it than that.

The road to 1914 did not begin in Sarajevo. It wound back through the centuries of dynastic accretions, nationalistic risings, family ties, and political intrigue. Author Margaret MacMillan leads the reader down that road with all its hills and valleys, twists and turns, peaceful solutions and ultimate disaster

The road to 1914 did not begin in Sarajevo. It wound back through the centuries of dynastic accretions, nationalistic risings, family ties, and political intrigue. Author Margaret MacMillan leads the reader down that road with all its hills and valleys, twists and turns, peaceful solutions and ultimate disaster

Order Now |

This book lays out the backdrop against which the actors played their roles. The Europe of 1900 displayed its splendors to the world at the Paris Universal Exposition as nations united by the ties of royal consanguinity and locked in colonial and economic competition outdid each other in presenting their civilization's march of progress that could never retreat. This civilization that was the master of the world lived in the shadow of the Franco-Prussian War and the challenge of a rising United States.

MacMillan then examines the circumstances of the major countries that would guide Europe through the days that lay ahead. Britain, where the reign of Victoria, whose grandchildren would send armies to their deaths, was giving way to that of Edward VII, still ruled the waves but had a military largely committed to the preservation of its empire. Germany was a new country whose childish Kaiser Wilhelm II, grandson of Victoria, imposed his own will of taking his place in the sun by expanding Germany's army, the development of a navy to challenge Britain's, and his own brand of international intrigue. France was a still proud power licking the wounds inflicted by Prussia even while its leaders privately recognized the need to move on. There were also the sick nations of Europe: Russia, a backward power developing with French loans and rebuilding from its defeat by Japan in 1904-05; Austria-Hungary an empire assembled by royal marriages but divided among Austrians, Hungarians, and minority nationalities as well as between the conservative and aging Emperor Franz-Joseph and his more liberal heir presumptive, Franz Ferdinand; finally, the sickest of all, the Ottoman Empire whose anticipated demise threatened to set the powers scrambling to pick up its pieces.

MacMillan then examines the circumstances of the major countries that would guide Europe through the days that lay ahead. Britain, where the reign of Victoria, whose grandchildren would send armies to their deaths, was giving way to that of Edward VII, still ruled the waves but had a military largely committed to the preservation of its empire. Germany was a new country whose childish Kaiser Wilhelm II, grandson of Victoria, imposed his own will of taking his place in the sun by expanding Germany's army, the development of a navy to challenge Britain's, and his own brand of international intrigue. France was a still proud power licking the wounds inflicted by Prussia even while its leaders privately recognized the need to move on. There were also the sick nations of Europe: Russia, a backward power developing with French loans and rebuilding from its defeat by Japan in 1904-05; Austria-Hungary an empire assembled by royal marriages but divided among Austrians, Hungarians, and minority nationalities as well as between the conservative and aging Emperor Franz-Joseph and his more liberal heir presumptive, Franz Ferdinand; finally, the sickest of all, the Ottoman Empire whose anticipated demise threatened to set the powers scrambling to pick up its pieces.

Click on Image to Expand

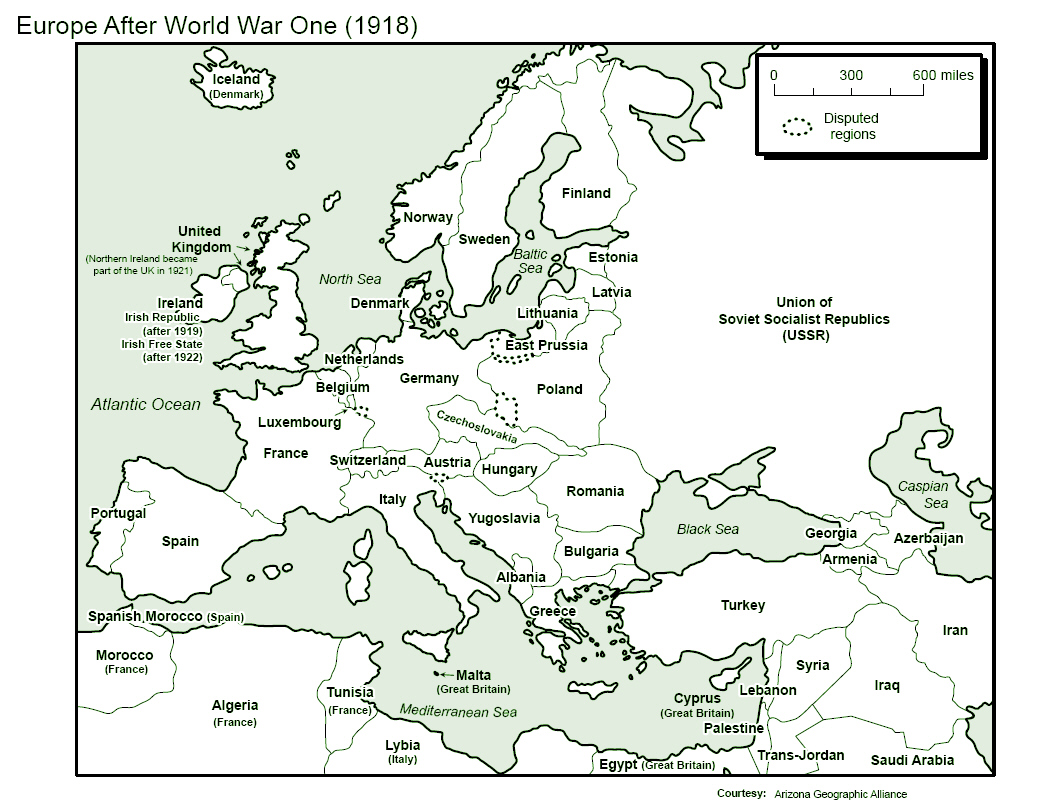

The Results of the Decisions of 1914

In each of these nations monarchs, soldiers and statesmen assessed their alliances, the balance of power, both now and in the future, and decided when to fight and when to make peace. Just as Fort Sumter was not necessarily where the Civil War would begin, the assassination of Franz Ferdinand was not the heaven-ordained powder keg that would set Europe ablaze — Bismarck's prediction that "One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans" notwithstanding. There were other potential sparks but the Concert of Europe, which had kept the peace since the Napoleonic Wars, was able to contain colonial ambitions, the Franco-German rivalry in Morocco, and a series of wars in the Balkans. By 1914 something had changed. Austria-Hungary felt that it must punish the Serbians in order to remain a great power. Germany, surrounded by France and a rising Russia, saw its relative position declining in the future so, if war was to come, the sooner the better. Russian and other leaders fearing socialist and other radical revolution found in war a foreign threat against which its people could rally. France foresaw its population imbalance with Germany worsening. To too many this was the time for a war that would, due to economic necessity, be short and relatively painless. Despite these forces peace attempts were made by some, including the Kaiser. Mobilizations were debated but ultimately were ordered. By the end of the book the lamps were going out all over Europe.

The actual story of the war is for other works and, perhaps, other authors. The War That Ended Peace is the story of the misjudgments, the false assumptions, the called bluffs, the unalterable plans, and the flawed characters that combined to extinguish the Lamps for a generation and cast a shadow over Western civilization to this day. The story is momentous. The writing is superb. Margaret MacMillan has crafted a book that never taxes the reader's interest nor lets the mind wander. She asks questions such as whether the German naval buildup, which had little effect once war started, deprived the army of the resources that might have made victory over France possible? One technique that she uses to great advantage is to draw parallels between the events and conditions of a century ago and those of current and recent times. We are left wondering "Was this war necessary?"; "Why could the Concert of Europe not keep the peace one more time?"; and, most frightening, "Could WE do it again?"

James M. Gallen

The actual story of the war is for other works and, perhaps, other authors. The War That Ended Peace is the story of the misjudgments, the false assumptions, the called bluffs, the unalterable plans, and the flawed characters that combined to extinguish the Lamps for a generation and cast a shadow over Western civilization to this day. The story is momentous. The writing is superb. Margaret MacMillan has crafted a book that never taxes the reader's interest nor lets the mind wander. She asks questions such as whether the German naval buildup, which had little effect once war started, deprived the army of the resources that might have made victory over France possible? One technique that she uses to great advantage is to draw parallels between the events and conditions of a century ago and those of current and recent times. We are left wondering "Was this war necessary?"; "Why could the Concert of Europe not keep the peace one more time?"; and, most frightening, "Could WE do it again?"

James M. Gallen

I think the thing that started the major powers (Great Britain, France, and Germany - Austria was already at war with Serbia) nfighting was Russia's "partial" mobilization which triggered the German railroad mobilization plans. The troops hit the borders and started firing and the general war started. Thoughts?

ReplyDeletetmorgan58@hotmail.com

Not only was it such a tragedy for the world, but it contained the seeds that ultimately led to continuation... as WWII. Such a tragedy for so many dead and displaced.

ReplyDelete