The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914

by Christopher Clark.

Published by Harper Collins, 2013

In The Sleepwalkers Cambridge professor Christopher Clark delivers a well-written and strongly argued account of how the Great War began. The author's approach and conclusions are unique in several ways. First of all, his focus is on the Balkans in general, and Serbia in particular, whose history he feels is one of the lost keys to understanding the outbreak of the war. The first third of the book is devoted to the tangled and very violent history of Serbia up to 1914. The second third of the book describes the diplomacy that led to the polarization of the five Great Powers into two antagonistic camps. It is only in the final third of the book that we arrive at the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 and the unfolding of the crisis that would lead to the outbreak of the war.

This book is also a revisionist history, presenting Austria-Hungary and Germany in a more favorable light at the expense of France and Russia. Moreover, rather that apportioning blame, the author feels that all of the powers were culpable in the collapse of peace. To quote from his conclusion,

There is no smoking gun in this story; or rather, there is one in the hand of every major character. Viewed in this light, the outbreak of war was a tragedy, not a crime.

Dr. Clark in great detail reconstructs the various threads that went into the making of each of the protagonists' foreign policies and world outlook. He does an outstanding job of considering all of these factors, including internal politics, imperial rivalries, institution limitations, and the personalities of the decision makers. The author contends that the diplomatic crisis erupting in the summer of 1914 was one of the most complicated in history. This complexity was compounded by the fact that each of the major powers often spoke with competing or conflicting voices that sent mixed messages to opponents, creating confusion that would lead to misreading of intent during the July crisis.

The author rejects the premise that Austria-Hungary was on its last legs. He presents statistics indicating the empire was rapidly industrializing and experiencing sustained economic growth. That is not to say that he ignores the ethnic challenges facing the Dual Monarchy, but he finds it ironic that the man whom he felt was best placed to deal with these problems was the doomed Archduke.

The assassination is presented as part of a series of terrorist actions aimed at the destruction of Hapsburg authority in the Balkans and the creation of a Greater Serbia. The small group of young pro-Serbian zealots, the equivalent of modern suicide bombers, if not sponsored by the government of Serbia, were at the very least trained, equipped, and infiltrated into Bosnia by officials of that government.

Dr. Clark feels that Austria had a just cause for war against Serbia. The problem was that it took Austria too long to secure the backing of Germany and to gain a consensus with Hungarian leaders before it could issue its ultimatum. Outrage over the assassination had subsided, and Russia had time to build a case that Serbia was not involved in the assassination, thus putting the onus of aggression on Austria.

The author rejects the idea that the German high command used the crisis to engineer a preventive war against Russia. In fact, Dr. Clark contends that Germany was the least involved of the powers until the last weeks of the crisis. In another point of revision, he claims that the Serbian reply to Austria's ultimatum, rather than a near complete capitulation, was instead, a "highly perfumed rejection on most points."

This book is also a revisionist history, presenting Austria-Hungary and Germany in a more favorable light at the expense of France and Russia. Moreover, rather that apportioning blame, the author feels that all of the powers were culpable in the collapse of peace. To quote from his conclusion,

There is no smoking gun in this story; or rather, there is one in the hand of every major character. Viewed in this light, the outbreak of war was a tragedy, not a crime.

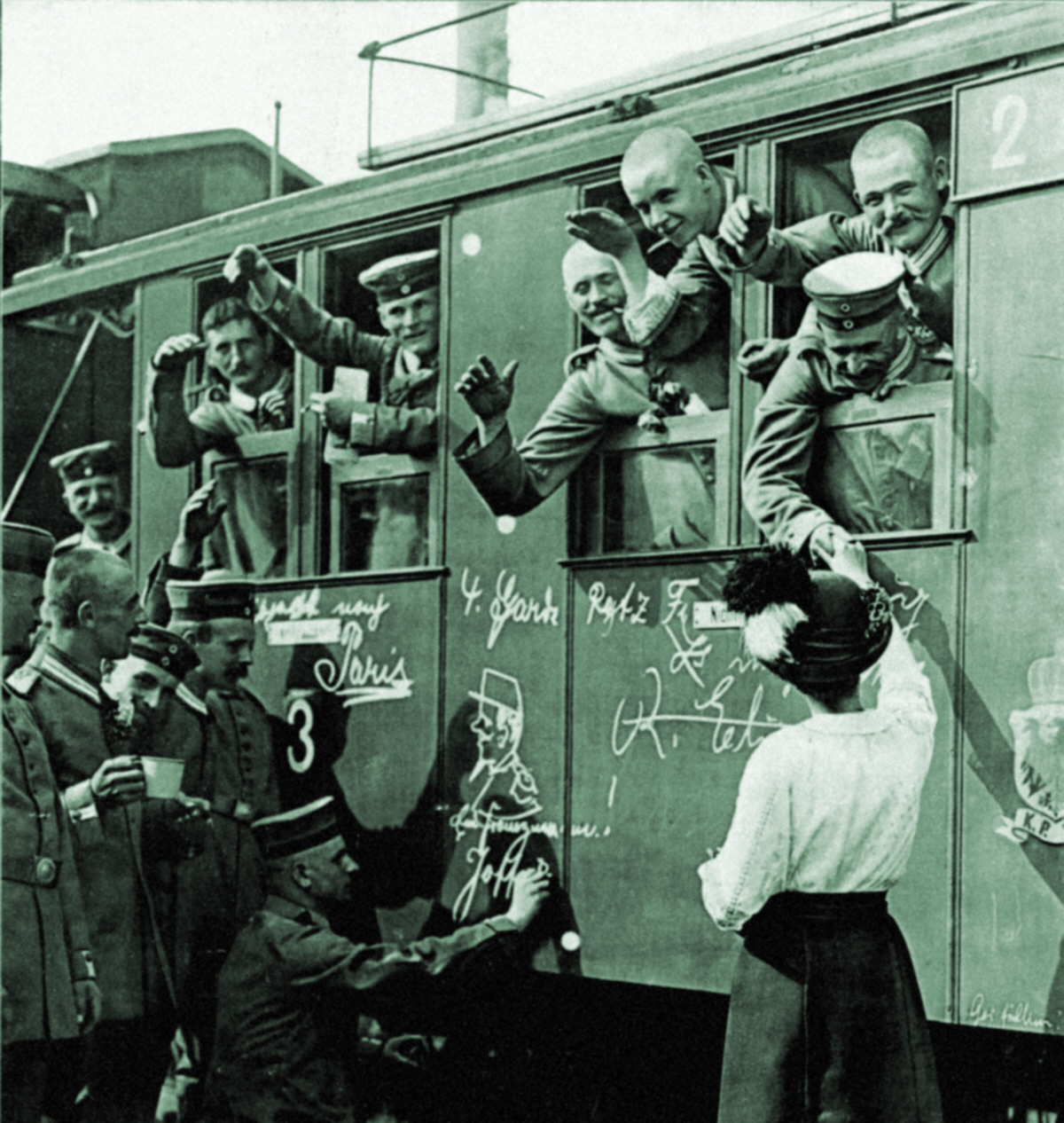

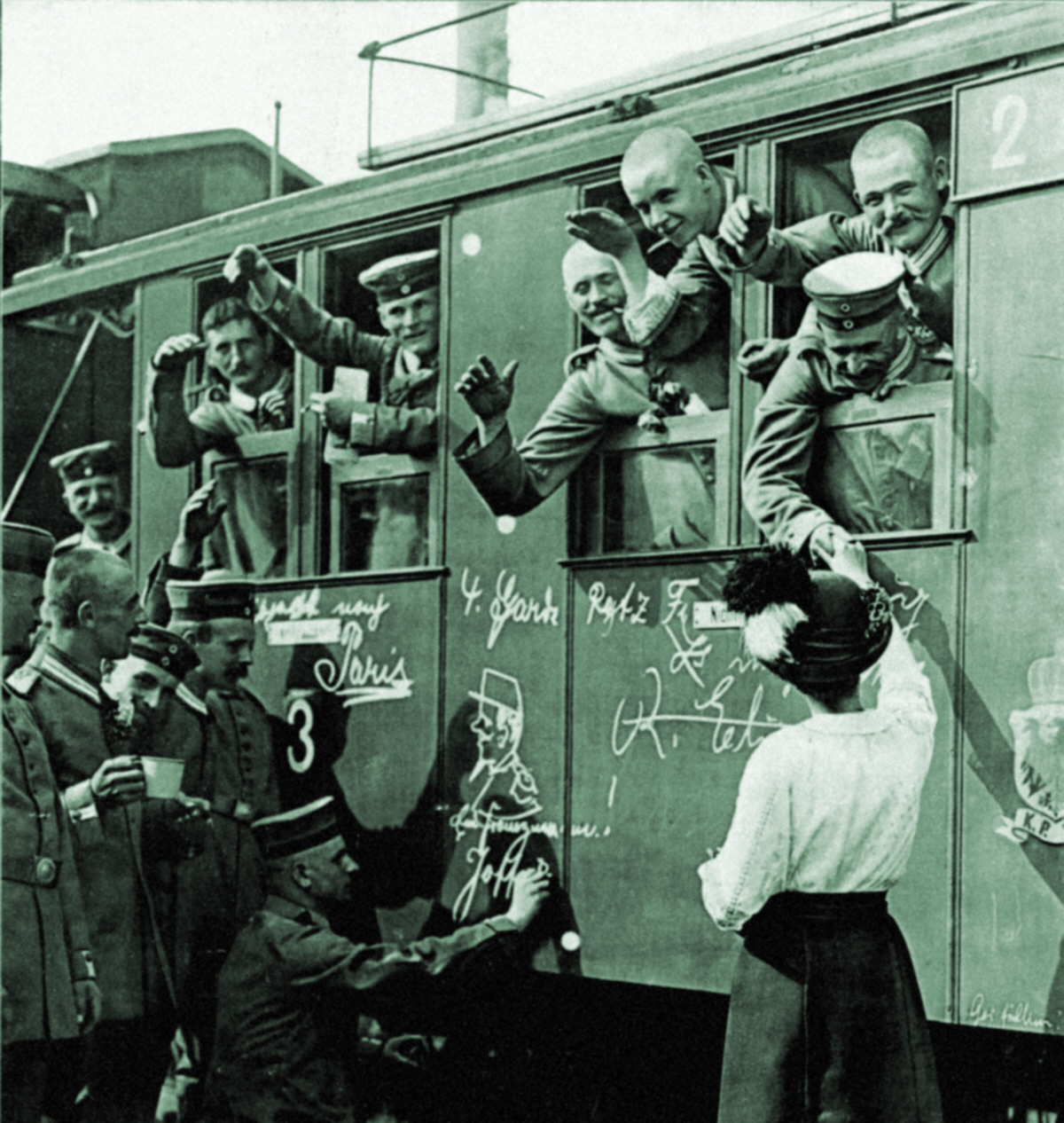

Click on Image to Expand

German Troops Departing Berlin, August 1914

Dr. Clark in great detail reconstructs the various threads that went into the making of each of the protagonists' foreign policies and world outlook. He does an outstanding job of considering all of these factors, including internal politics, imperial rivalries, institution limitations, and the personalities of the decision makers. The author contends that the diplomatic crisis erupting in the summer of 1914 was one of the most complicated in history. This complexity was compounded by the fact that each of the major powers often spoke with competing or conflicting voices that sent mixed messages to opponents, creating confusion that would lead to misreading of intent during the July crisis.

The author rejects the premise that Austria-Hungary was on its last legs. He presents statistics indicating the empire was rapidly industrializing and experiencing sustained economic growth. That is not to say that he ignores the ethnic challenges facing the Dual Monarchy, but he finds it ironic that the man whom he felt was best placed to deal with these problems was the doomed Archduke.

The assassination is presented as part of a series of terrorist actions aimed at the destruction of Hapsburg authority in the Balkans and the creation of a Greater Serbia. The small group of young pro-Serbian zealots, the equivalent of modern suicide bombers, if not sponsored by the government of Serbia, were at the very least trained, equipped, and infiltrated into Bosnia by officials of that government.

Dr. Clark feels that Austria had a just cause for war against Serbia. The problem was that it took Austria too long to secure the backing of Germany and to gain a consensus with Hungarian leaders before it could issue its ultimatum. Outrage over the assassination had subsided, and Russia had time to build a case that Serbia was not involved in the assassination, thus putting the onus of aggression on Austria.

The author rejects the idea that the German high command used the crisis to engineer a preventive war against Russia. In fact, Dr. Clark contends that Germany was the least involved of the powers until the last weeks of the crisis. In another point of revision, he claims that the Serbian reply to Austria's ultimatum, rather than a near complete capitulation, was instead, a "highly perfumed rejection on most points."

Order Now |

So the crisis moved on toward war. Dr. Clark points out that while Germany is often blamed for giving Austria a blank check, France gave Russia the same assurances just before the crisis.

The author believes that war occurred in great part because of a mind-set shared by the decision makers of 1914. Previous crises had taught them to hold firm and not back down. Allies had to be fully supported. While no one wanted war, each of the major players viewed their own actions as defensive and that the decision for war or peace lay with their opponents. Only this time there was no bluff to be called and no one would throw in their hand.

This is a provocative book challenging much of the standard accounts of the beginning of the war. It is well researched and colorfully written. The author does an exceptional job portraying many of the characters in this tragedy, from the aloof and diffident Sir Edward Grey to the bombastic Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Austrian chief of staff who had counseled war during each crisis but, when finally given the green light to go to war against Serbia, had to admit that his army was not ready to fight. This publication deserves a place on the bookshelf of every student of the approach of the Great War.

Clark Shilling

The author believes that war occurred in great part because of a mind-set shared by the decision makers of 1914. Previous crises had taught them to hold firm and not back down. Allies had to be fully supported. While no one wanted war, each of the major players viewed their own actions as defensive and that the decision for war or peace lay with their opponents. Only this time there was no bluff to be called and no one would throw in their hand.

This is a provocative book challenging much of the standard accounts of the beginning of the war. It is well researched and colorfully written. The author does an exceptional job portraying many of the characters in this tragedy, from the aloof and diffident Sir Edward Grey to the bombastic Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Austrian chief of staff who had counseled war during each crisis but, when finally given the green light to go to war against Serbia, had to admit that his army was not ready to fight. This publication deserves a place on the bookshelf of every student of the approach of the Great War.

Clark Shilling

Excellent review! I've had the book on my shelf since it was published, as I knew it would be a fascinating read!

ReplyDeleteThank you for your kind words. Yes, it is a fascinating read. There are several other books that have come out recently about the start of the war I have not had a chance to read. One has been reviewed on this blog. I like Dreadnought by Robert K. Massie and Europe's Last Summer by David Fromkin, as well as the classic Guns of August.

DeleteComment from Donald Conrad:

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately, the author fails to identify the major ECONOMIC problem that existed between England and Germany. Consider the need to remove German competition against a sagging English economy. England could not do it alone. Enter France. A chance to gain revenge for the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. Bring in Russia, in spite of its lost to Japan, and provide her with millions of franks to build her military might. They knew that Germany had made a weak alliance with Italy and Austria-Hungary. One spark in the Balkans could bring the forces, except Italy, into a two front war. A victory for the Allies would reduce Germany to its pre-1872 existence. Their is a major need for a psychological understanding of all the leaders.

Donald, thank you for your comment. It appears to me that there was no overall plot to launch a war for whatever reason, but certainly not for economics. I think that is the overall message of Sleepwalkers - all the statesmen were running around making commitments and pushing thier allies, but no one ever stopped to think through where was all of this leading. As far as economics, if that was the driving force for Britian, then why did they not feel threatened by the United States, who was as much an economic threat as Germany, and who under Roosevelt was building a large navy?

DeleteExtremely thin wold view for a university professor... Even a shallow look into Serbia in those days gives you a sad, under-developed country, exhausted by several wars, and a big loss of population. Certainly not a fire-starter with a gigantic neighbor. Investing so much energy in blaming them for something much much bigger is really an underachievement.

ReplyDeleteAs many crazy things, if you pretend this is plausible, that this weak country with zero military capacity decided to bring down Austria to its knees, everything else can be retro-fitted into some plot. But, again, for a PhD, and a professor, an underachievement.

As for its literary value - a nice read, though...

Thank you for the post! I'm starting to learn about these things in history class and I think that this is helpful to know. It brings in a good perspective for me.

ReplyDelete