Orders to mobilize came in code on 6 April 1917 at 9:15 p.m., just hours after the United States Congress declared war on Germany. It was Good Friday, and USS Wolverine Commander William Leverett Morrison had been waiting for the call in the Pennsylvania Naval Militia office at Erie’s Federal Building. America was at war, and his crew would be the first men in Erie County to see active service in the Great War. Divisions C and D of the Naval Force of Pennsylvania had been drilling all week in anticipation of the news. It could be argued that they had long been training for this—in August of 1915, just a few months after the sinking of the Lusitania, the Wolverine hosted preparedness exercises on Lake Erie for all of the Great Lakes states’ Naval Militia ships. When America went to war, Navy men would be ready.

|

| USS Wolverine (Formerly USS Michigan) Patrolling Lake Erie |

The crew was ordered to report to the ship, in her usual berth at the Public Steamboat Landing, most often known as the Public Dock, by noon on Saturday 7 April. From that point forward, most of the crew lived aboard until departure orders came, thus sacrificing an Easter holiday with loved ones while they waited.

On Tuesday 10 Apri, over a hundred sea gulls, considered by sailors an omen of good luck, flocked around Wolverine all day as her crew had dinner together on board and made ready to depart. At 6:00 p.m., their sea bags already loaded on the train, the crew lined up on the dock opposite their ship. Commander Morrison gave the order, “Forward, march!” and they were on their way. A special train bound for League Island Navy Yard (Philadelphia) awaited them at Union Station, ready to depart right after the regular 6:45 train left.

All but the most recent recruits were smartly turned out in uniform, and all wore a look of determination that belied the emotions they felt as they marched up State Street. At Second and State they acquired an escort that included the Power Boat Squadron captains and Erie Yacht Club crews, a personal compliment to Commander Morrison, who was instrumental in organizing those groups. Civic leaders, including Mayor Miles B. Kitts, local fraternal orders with their bands, and the Citizens’ Protective Association all fell in to honor the crew. The previous day, the association had presented the departing sailors with four gross of tobacco, matches, and shoe polish. Crowds lined both sides of the street the entire way, with even more people shouting their best wishes from upper floor windows of State Street businesses. The newspaper estimated the crowd to be 5,000 people. At the head of the march, Lt. Cmdr. William L. Morrison led Division C, along with Lt. Armand Kessler and Surgeon J. T. Strimple. Ensign Peter Schaaf, Jr., led Division D, as Lt. N.R. Wilbur was unable to march due to illness.

|

| Wolverine Crewman Grant Floyd Cowley Would Be Assigned to the Battleship USS Iowa and the transport USS Artemis |

The columns marched amidst cheers and flag waving all the way to Turnpike, where the “tars” turned right to the train station. Their escort lined up and saluted them as they passed on their way down to the south platform, where they broke ranks to receive final handshakes, small packages of “eats,” and teary farewell kisses from mothers, wives, and sweethearts. Bands kept things lively, playing patriotic airs while they waited. The Star-Spangled Banner finale was prematurely played in the confusion when the regular 6:45 train departed. Delays held the special until it finally departed at 7:30. Erie’s “jackies” were scheduled to de-train within a block of the Navy Yard the next morning at 8:00.

Though they left together, once in Philadelphia they were assigned to cruisers and gunboats of the United States reserve fleet to fill out the complement of enlisted men. They would now be in the “blue water Navy.” Several Wolverine crewmen, such as African-American brothers Fred and Robert Vosburgh, were assigned to USS Iowa. This receiving ship spent six months in Philadelphia, then went to Hampton Roads, training men and guarding the entrance to Chesapeake Bay for the remainder of the war. Specialists in what was then cutting-edge technology (electricians and radio operators) found more adventurous service as overseas transport in USS Artemis or in USS Chicago at the submarine base at New London, Connecticut. While many were fortunate to find an old mate in their new assignments, the Wolverine crew did not serve again together as a unit during the war.

|

| USS Iowa—Stopping Off Ship for Some Wolverines |

Although he marched to give his crewmates a good send-off, Ensign John P. Smart remained in Erie in command of Wolverine. Along with Chief Boatswain’s Mate F.S. Poole, he was tasked with recruiting new men to fill Divisions C and D again, and take them, with Wolverine, to United States Navy Great Lakes Training Station in North Chicago. Before accepting volunteers for the reserve force, however, they recruited and sent men directly into Navy service, dispatching those not accepted in time to leave with Wolverine’s crew to Buffalo for assignment. Navy enlistments in Erie surpassed the Army, nine sailors to every one soldier, in the weeks around the declaration of war, and Polish-Americans surpassed all. Poole is quoted in the Erie Dispatch on 11 April, “Poles are the best Americans we've got. I never knew it until I came to Erie. I never saw such a bunch eager to get into this fight in my life.” Of the 45 applications for enlistments in the Navy that week, more than 50 percent were men of Polish descent. Sent to Buffalo that day were Joseph W. Gdaniec, John J. Kudiak, Walter K. Kuczynski, and Roy P. J. Kriquelstive, all from Erie; also Russell G. Shearer, Cambridge Springs, and James J. Burke, Dunkirk, Chautauqua County, New York.

Several of Wolverine’s previous crew were called up or reenlisted as well. Ensign Landis E. Isaacs had already been assigned to USS Connecticut, where he would ultimately earn promotion to lieutenant, then serve as Navy inspector at Erie Forge. Twelve-year Navy veteran William Henry Stine reenlisted in March 1918, then sent to serve as coxswain on USS Shawmut, part of Mine Squadron One on its way from Boston to the North Sea. A most hazardous operation, Naval staff referred to these men as “living on the edge of eternity,” because they went to sea in ships packed with high explosives. In five months, they planted 56,571 mines in the 250-mile North Sea Strait between Scotland and Norway.

Notably, two of the men who marched with Erie’s first to serve in World War I answered our nation’s call again in World War II. Charles Blake Alloway served in the United States Army in WWII, retiring as a U.S. Army major. Frank Grucza tried to join the Navy in 1942 but was rejected as too old, so he joined the Merchant Marine. He was awarded the Merchant Marine Combat Bar, the Atlantic War Zone Bar, and the Mediterranean Middle East War Zone Bar for his service in WWII.

--------------------------------------

About Answering the Call

|

| The Erie County WWI Centennial Committee Who Produced Answering the Call |

This article is simply one of over 40 different perspectives of Erie County, Pennsylvania's participation in the Great War collected in Answering the Call, a wonderful piece of Americana. It profiles fully the efforts, sacrifices, and adventures of the citizens of one of America's 3,140 counties during the Great War. Proceeds for the sale of this book will be used for the preservation of the World War I Memorial at Erie County Veterans Memorial Park.

|

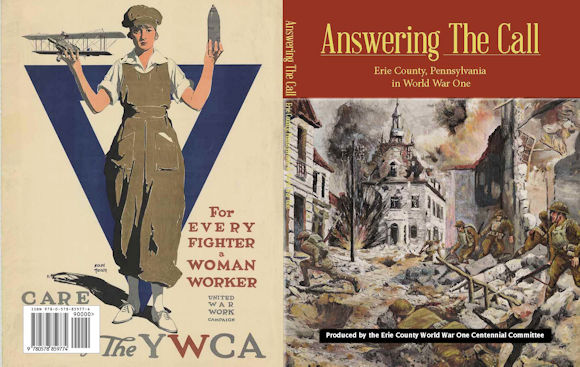

| Cover Art |

For Purchasing Answering the Call: Erie County, Pennsylvania in World War One:

· $22 per softbound copy, plus $5.00 shipping, with all proceeds going toward the maintenance and upkeep of the World War I memorial at Erie County Veterans Memorial Park.

· For information on the book, or to request a copy, email eriecountyww1@gmail.com or call 814-868-2225.

I have read that the Detroit Yacht Club purchased a small steamer, had a cannon mounted and patrolled off Cuba during the Span Am.War This is off topic but Great Lakes involvedz, Anyone know of any lite

ReplyDelete..any literature with an account of this affair?

ReplyDeleteThank you..

Lee, the story was drawn from newspaper accounts published primarily in "The Erie Dispatch", April 3 through 13, 1917, and subsequent research done on the men whose names were listed in the articles. Information on a couple of the men's service came directly from interviews with their grandchildren.

ReplyDelete