|

| Gatchina Gate in Catherine Park, 1910 |

Natalia Ivanova

On the eve of the First World War, 30 July 1914, the capital of the Russian Empire, St Petersburg, along with its surroundings, was declared under martial law. The Governor General had been granted broad powers. He was able to: make regulations relating to the prevention of violations of public order and national security; forbid either public or private meetings; shut down commercial and industrial enterprises; stop the publication of periodicals; banish individuals from the city; close educational institutions; impose, from the date martial law was declared, the sequestration of property and the seizure of movable property along with any income from such, remove officials of all departments from office. Violation of the regulations meant the threat of a fine of up to 3,000 rubles or incarceration for up to three months, and furthermore the perpetrator could be brought before a tribunal. On 31 July, the German Ambassador, Pourtalès, delivered a note to the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, S. D. Sazonov, declaring war. For the first time in the history of the country the order was given for general conscription and, on the same day, conscripts were sent to assembly points .

A popular slogan in the country was the struggle against “German domination.” St Petersburg was renamed Petrograd on 1 September. . . The German Embassy was taken over; an enraged mob on top of the building threw down a quadriga [statuary of a chariot drawn by four horses], and it sunk in the river. The next day, the United States’ Attorney came in protest to the Minister for Foreign Affairs, S. D. Sazonov, to protect German nationals and their property in Russia. In the town, urgent measures were taken to dismiss those “suspected” of being German or Austrian nationals from all agencies. German and Austrian citizens were stripped of their titles of commercial and manufacturing advisors. It was subsequently proposed that they all be deported to Germany via Sweden and Finland. All activity of German and Austrian societies was banned, as well as German language teaching at Lutheran, Catholic, and reformed schools.

|

| In Front of the Winter Palace on the Declaration of War |

For the entire period of martial law, censorship was imposed on the press. “White spots” appeared in the newspapers, caused by censorship edits. Bank branches in Riga as well as Libava and Vindava were closed, and all banking operations were planned to be conducted in Petrograd and Moscow. As a result of military action in the city, there was an increased interest in geographical maps and the prices for these rose by 20 to 30 percent.

[In a few weeks] the price of matches and other essentials had risen sharply. Angry buyers at one of the markets attacked sellers who were trying to punish looters. The incident was linked to the high cost of the first phase of high prices and was discussed at a meeting of the Duma. Limits were set on food prices. Those responsible for illegally raising food prices were placed under arrest for three months. Trade restrictions were imposed on strong spirits, and then sales of vodka were banned. More severe punishments were introduced for street demonstrations. Income tax rose and tariffs for passenger and goods transport went up by 20 percent.

To Petrograd came an increased influx of wounded from the battlefield and refugees from the occupied territories also flocked here. More and more infirmaries opened, and on opening they were blessed by priests. The various institutions created nursing courses for women and priests. In all the city churches, prayers were said “to award victory to Russian and Allied weapons.” Public organizations collected donations to help the wounded. Even in prisons the production of cotton wool was organized to assist hospitals.

However, many residents of Petrograd carried on their life as before. They continued to attend the city’s two racecourses, where turnover increased considerably. They attended football matches as the Football League opened its autumn season. Theaters continued operating in the city. At the end of August they were putting patriotic performances into their repertoire. Within the context of the struggle against “German domination,” there was a ban on musical performances and season tickets for the German composer Wagner. Normal life continued, and, in educational institutions, the next academic year began in universities and high schools. However, in the universities it became necessary to show evidence of trustworthiness and it was forbidden to accept German and Austrian nationals. In general education schools for girls, they organized hot breakfasts and introduced needlework courses; students were involved in the manufacture of linen for the wounded.

The start of the war highlighted the shortcomings and weakness of the Russian economy faced with the conditions of military action. Many businesses received materials from abroad and had no stock. Germany had been the almost exclusive supplier of raw materials for Russian industry. In addition, fuel prices increased significantly. Companies closed due to conscription, and output was reduced. And, as a consequence, the weakest manufacturers went into liquidation. As factories closed down, unemployment began to take hold. At the same time, however, new enterprises were established in Petrograd. For example, the “Russian Renault” car company opened with a capital of one million rubles. The International Commercial Bank made a significant profit.

In the context of the fight against drunkenness in Petrograd, a number of inns, restaurants, wine cellars, etc. were closed down, but wine was left for Church sacraments.

Refugees and many inhabitants from the countryside, whose husbands had left for the front, turned up in Petrograd, attempting to find positions as servants, nannies, cooks, or maids. To replace the men who had left for war, there were now women telegraphists. As many women were now starting to work, there was an increase in child neglect and consequently higher levels of juvenile delinquency. Cases of theft became more frequent. A theft of soldiers’ boots from a military warehouse provoked a strong response in the city .

Prisoners of war appeared in Petrograd, and an order was issued forbidding them to visit inns, restaurants, clubs, coffee shops, theaters, or circuses. Prisoners of war were only allowed into shops under escort. Whilst walking in the streets either in groups or alone, they were not allowed to associate with residents or hand anything over to them

At the end of 1914, the dismissal of Germans and Austro-Hungarians from companies and organizations continued. An order was issued to evict from Petrograd Austrian and German nationals aged 17 to 60 to a distance of 100 verst [1 verst = 1066.8m]. Those who failed to comply were condemned to permanent forced labor. At a meeting of the Duma, Deputy Levashov posed the question “about German domination,” and a Special Committee was set up to deal with this struggle. On 1 January 1915, publication of the German language newspaper Petrograder Zeitung ceased.

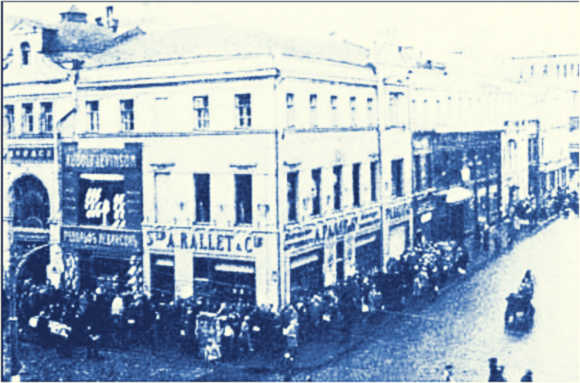

|

| Early War Food Lines |

In March 1915, at the front, the Russian army began to retreat, and life in Petrograd grew even worse. The political crisis in the capital intensified, economic collapse worsened and at the same time opposition and revolutionary sentiment within society increased. Disruption to the fuel supply made life very difficult within the transport sector. Inflation escalated. By the end of March, the prices of meat, sugar, and firewood had increased. Continuous shortages of flour and coal were recorded. At the same time, prohibitions for workers intensified: the game of billiards was banned, as were other gambling-related games.

The food crisis escalated in all areas of Russian society, and by autumn of 1916 it had reached its peak. This manifested itself in the collapse of food supplies, [inflation], and the accelerated breakdown of authority. Furthermore, the influence of the Bolsheviks on events in Petrograd became more open. The growing crisis demanded that the authorities take more decisive action, but they did not. [Revolution was coming.]

Source: "Petrograd: First World War (1914–1918)", Brusselse Cahiers 2014/1E

This is a most interesting and informative article.

ReplyDeleteAgreed!!

ReplyDeleteSome of the conditions in Petrograd at the beginning of World War 1 seem to resemble what is going on in Russia today, according to a Russian friend.

ReplyDelete