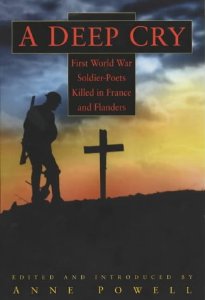

A Deep Cry: First World War Soldier-Poets Killed in France and Flanders

By Anne PowellPublished by Sutton Publishing, 1998

When you come across a poem such as “To My Daughter Betty, The Gift of God” in Anne Powell’s anthology A Deep Cry, you can’t help being poignantly reminded of the book’s subtitle: First World War Soldier-Poets Killed in France and Flanders. Every poem in this 470-page anthology in a sense represents a great loss—of a man and of talent that might have produced so much more, as well as the loss of a father, husband, brother, or son.

Sixty-six British poets are represented in this collection. Not only were they all killed on the Western Front, but all were already published poets. Some were aristocrats, some were working-class, and many were somewhere in between, but all help confirm that for the first time Britain was fielding an army possessing a high level of literacy. Some, such as Sergeant J.W. Streets or Captain E.F. Wilkinson, MC, may never have been heard of by most of us, while others such as Wilfred Owen or Charles Sorley are well known as war poets.

In this remarkable book Powell presents each poet chronologically in order of their deaths and gives brief backgrounds of their lives, a description of the battle in which they died, and relevant excerpts from their letters and diaries. She also provides maps and lists of the cemeteries in which they lie (or the memorial on which they are named), all providing us with a touching picture of the poet as a human being.

As we read through Powell’s collection, first published in 1993, we see evidence of the truth behind Paul Fussell’s claim in 1975 that the Oxford Book of English Verse “presides over the Great War in a way that has never been sufficiently appreciated [1].” So many of the poems in Powell’s book show the writers not only to be familiar with the best of English poetry through the ages but also quite willing to emulate, borrow from, and even caricaturize it. Medieval literature is echoed in a few short poems, while Shakespeare and Milton are reflected in several sonnets. One poet admits to writing in the style of Kipling while another parodies Yeats (“I will arise and go now, and go to Picardy,/ And a new trench-line hold there…”). A.E. Housman is present if only because an officer of the Royal Naval Division used blank pages in his copy of A Shropshire Lad to write some of his own work on.

Anne Powell has done an admirable piece of work by selecting, organizing, and editing this book. For me, part of the effect comes from the context in which the poetry is presented. Powell does not give us some sort of Dead Poets’ Society publication. Instead she provides an outpouring of poetic expression from young men who well knew what death was all about and who, as they called on their Muse in trench, dugout, or hospital, knew that they may well be writing their last lines—as indeed they were. But all had the same hope (why else bother to write anything?) even though that hope was not to be realized:

David Beer

Sixty-six British poets are represented in this collection. Not only were they all killed on the Western Front, but all were already published poets. Some were aristocrats, some were working-class, and many were somewhere in between, but all help confirm that for the first time Britain was fielding an army possessing a high level of literacy. Some, such as Sergeant J.W. Streets or Captain E.F. Wilkinson, MC, may never have been heard of by most of us, while others such as Wilfred Owen or Charles Sorley are well known as war poets.

|

As we read through Powell’s collection, first published in 1993, we see evidence of the truth behind Paul Fussell’s claim in 1975 that the Oxford Book of English Verse “presides over the Great War in a way that has never been sufficiently appreciated [1].” So many of the poems in Powell’s book show the writers not only to be familiar with the best of English poetry through the ages but also quite willing to emulate, borrow from, and even caricaturize it. Medieval literature is echoed in a few short poems, while Shakespeare and Milton are reflected in several sonnets. One poet admits to writing in the style of Kipling while another parodies Yeats (“I will arise and go now, and go to Picardy,/ And a new trench-line hold there…”). A.E. Housman is present if only because an officer of the Royal Naval Division used blank pages in his copy of A Shropshire Lad to write some of his own work on.

Anne Powell has done an admirable piece of work by selecting, organizing, and editing this book. For me, part of the effect comes from the context in which the poetry is presented. Powell does not give us some sort of Dead Poets’ Society publication. Instead she provides an outpouring of poetic expression from young men who well knew what death was all about and who, as they called on their Muse in trench, dugout, or hospital, knew that they may well be writing their last lines—as indeed they were. But all had the same hope (why else bother to write anything?) even though that hope was not to be realized:

| Oh! When shall I know the sweet joy of returning, Mother and sweetheart to welcome me in, Forgetful of suff’ring – Death and the fighting Happy once more in the midst of my kin.

(Private John Baker, d. 8 August 1918, age 21)

|

[1] Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory, OUP, 1975, p. 159.

A Shropshire Lad is A. E. Housman not Hardy.

ReplyDeleteThanks for that. Correction posted. MH

ReplyDelete