This initially appeared on Trenches on the Web in 1997.

|

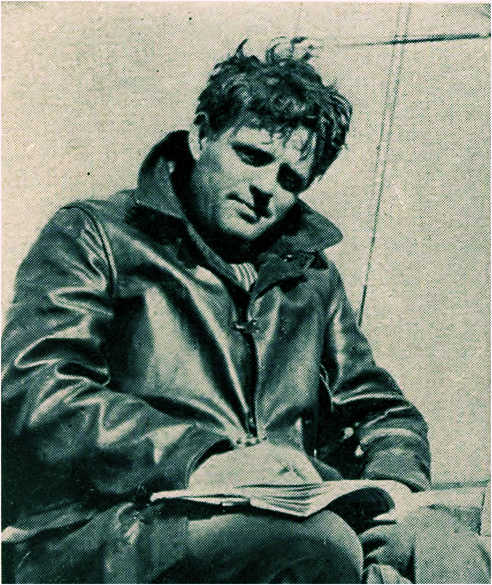

| Jack London, 1915 |

Jack London on the Great War

By Michael E. Hanlon

The world has turned many times since the day my father sold Jack London a newspaper at some boxing venue in San Francisco and the famous author and newspaper correspondent goodnaturedly chatted with him briefly. That chance meeting long-ago, insured that London's works would be well represented in my early reading. When I escaped the childrens' department and made my initial visits to the adult section of our neighborhood library, Dad came along to help me select my books. THE SEA WOLF was the second 'adult' volume I ever read. [For some reason lost in memory, Dad's first pick was Zane Grey's RIDERS OF THE PURPLE SAGE.]

Subsequently, I went through a long period devouring every volume the library possessed of Jack London's works. I recall enjoying the Alaskan adventure yarns a lot more than, say, the SCARLET PLAGUE in which a worldwide pandemic was prophesied, or the IRON HEEL, which projected war between Germany and the United States as well as the rise of a totalitarian reaction to a successful socialistic revolution. But in those days I had yet to hear of the Spanish Flu or the rise of fascism, so I had no appreciation of how "cutting-edge" Jack London could be when inspired.

In college, I experienced another phase learning about him in his roles of journalist and social critic. George Orwell, I had read, considered THE ROAD, London's memoir of his hobo, vagabond days as his greatest work. This started me reading all the author's nonfiction works including the truly excellent despatches from the front lines of the Russo-Japanese War.

At some point, I moved on from Jack London's literature, and eventually developed my abiding interest in history and in the Great War of 1914–1918. For a long time, I parked Jack London and World War I in different stalls in my memory garage. Then one day recently, I saw a reference to London's last assignment as a war correspondent—he had accompanied the U.S. forces on their punitive mission to Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914. Something clicked and I started asking myself what London, who died on 22 November 1916, might have done in the way of reporting [or at least commenting] on the first two years of the war in Europe.

My researching efforts were not very successful at first—his biographers are sketchy on this subject—but finally, the historian at Jack London State Park in Glen Ellen, California, steered me in the right direction. He put me in contact with Winifred Kingman, operator of the nearby Jack London Bookstore, whose late husband Russ was a London biographer and authority. Winifred agreed that World War I was just too big of an event for a dynamic and curious individual like Jack London to ignore. She was kind enough to search through the indexing of her husband's 50,000 [!] reference cards and discovered some revealing material. It required only some minor editing to organize things and to cull-out London's occasional ventures into Nietzschean and socialistic theorizing. What emerged is the same eclectic mixture of incisiveness and intellectualizing that characterized most of London's work.

Rather than supply full commentary, I have decided to take a documentary approach for the rest of this piece, using the best of the material supplied by Winifred Kingman. Here is Jack London, with minimal annotating by me, discoursing on the coming and early years of the Great War:

EARLY PREDICTIONS ON WAR IN THE 20TH CENTURY

"Soldiers [in the future] will be compelled to creep forward, burying themselves in the earth like moles...

"Future wars must be long. No more open fields; no more decisive victories; but a succession of sieges fought over and through successive lines of widely extending fortifications. The defeated army — supposing that it can be defeated — will retire slowly, entrenching itself step by step, and most likely with steam 'entrenching machines.'

"The artillery has come to be greatly relied upon. Competent military experts hold that French artillery has increased in deadliness in the past thirty years one hundred and sixteen times. This has been made possible by the use of range-finders, chemical instead of mechanical mixtures of powder, high explosives, increase of range, and rapid fire."

From OVERLAND MONTHLY, March 1901

[Despite the accuracy of these predictions, the completed article somewhat illogically forecasted the end of large-scale warfare.]

|

| Vera Cruz Mexico, 1914: Correspondents (L-R) Jimmie Hare, London, Frederick Palmer, Richard Harding Davis |

GETTING TO THE FRONT

"Jack London to Go to War Scene! — Just Waiting for Big Battle — Preparing to Leave"

Headlines, San Francisco Call, August 14, 1914

In October 1914, Colliers Magazine offers to hire London as a war correspondent, but he declines upon learning it is impossible to get to the front without being arrested. [Russ Kingman Note, source unknown]

"I am looking forward, however, soon or late to going to Europe (soon as reporters [are] allowed to go to front.)

Letter to Dear Friend Braam, December 11, 1914.

Jack London, however, never made it to the Western Front. He would spend about two-thirds of his last 18 months visiting Hawaii trying to regain his failing health.

ON PREPAREDNESS

"Get a Gun! Says London"

Headline, San Francisco Bulletin, August 31, 1915

"I may add to my views on War that I think our National Guard a silly effort at preparedness; and that I believe in compulsory universal military service for our country for as long as there are gun-fighting nations liable to shoot at us." J.L.

Inscription in Lt. Willson's copy of LOVE OF LIFE

ON THE WAR IN EUROPE

"Warn the Kaiser...[of]..."The inevitability of war [with America]"

Letter to George Sterling, January 13, 1915.

"All I have to say about Germany is: Germany [is like] a big, stupid, blundering child that thought it thought like a man."

Letter to Mr. Mills, June 8, 1915

"I wish to tell you that I am profoundly pro-ally. I believe that the present war is a war between civilization and barbarism, between democracy and oligarchy...War is a silly nonintellectual function performed by men who are themselves only partly civilized, or by men who are really civilized and who must [face?], in battle, the barbaric attack of barbarians."

Letter to John Malmsbury Wright, September 7, 1915

" I believe the world as far as concerns not individuals, but the entire race of man, is good. The world war has compelled men to return from the cheap and easy lies of illusion to the brass tack and iron facts of reality. It is not good for man to get too high up in the air above reality. The world war has redeemed [humanity] from the fat and gross materialism of generations of peace, and caught mankind up in a blaze of the spirit. The world war has been a pentecostal cleansing of the spirit of man."

Comments to Pathé Exchange, June 16, 1916

[This intellectual's view that is slightly weird sounding today was by no means exclusively London's. The Italian critic Benedetto Croce made similar points in urging his country to declare war in 1915.]

Jack London, who once wrote, "So much of the game has been gain, though the gold of the dice has been lost," lost his life, possibly at his own hand, November 22, 1916.

Russ Kingman's PICTORIAL BIOGRAPHY OF JACK LONDON and a visit to Jack London State Park, Glen Ellen, Valley of the Moon, Sonoma County, California, are recommended to all. My favorite works by London include all of his short stories and reporting, his semi- autobiographical works MARTIN EDEN and JOHN BARLEYCORN, and that novel about the tyrannical sea captain Wolf Larsen that my father, the former newsboy, handed me at the Mission Branch of the San Francisco Public Library once upon a time.

With thanks to the rangers of Jack London State Park and Winifred Kingman.

London was right about his inability to get to the front in 1914...or ever, really. Both the French and British severely limited war correspondents until 1917, after London had passed.

ReplyDeleteThank You for your informative article on Jack London. I will be studying his work because of this article. His writing style would have influenced societal and literary perspectives on international conflict, human nature, and the human cost of war. His insights would have been interesting concerning international relations, nationalism, and imperialism, depicting the complex web of alliances and animosities that characterized the war. Thank You again.

ReplyDelete