From In Their Own Words at the Doughboy Center

Nearly every fellow's parents and sweetheart were down to the train to see us off. Will, Del, and myself rode down with Art in his machine. The send off we received was a royal one and gave us a thrill we will long remember. Bill, Del, Ensley, and I were put into different cars but we managed to get to-gether despite specific orders not to leave our coaches. After four different officers had counted us to see that none were missing we finally pulled out for a destination unknown. As soon as we passed Delray and crossed the Pere Marquette tracks I knew that we were on the Toledo division and were going around Lake Erie. Donations of tobacco and gum that had been given us were passed around and we settled ourselves for a long journey passing the time in various ways; some playing cards, others shooting craps, and still others singing and playing string instruments which they had brought along.

Pvt. Hazen S. Helmrich, Base Hospital 17

Diary

|

| Departure |

Dear Aunt,

Well we are in NY. At last we arrived last night about nine o clock we are now on the Hudson river about 20 miles from NY on the New Jersey side. We are going to be here tell they get us every thing for over seas service. That will take about two or three days. We have to be examined again before we leave.

Well Minnie I never had a better time in my life than I did on this trip. We were yelling at everything even like hills and trees. When we went through a city we were all hanging out the windows and yelling with all our might we were met at every station by people they were sure glad to see us they waved flags and thrower kisses at us at home the people are nothing like the people here they are more connected with the war. When we arrived at new Jersey City We were met by a lot of girls some of the boys went a little strong on there talk those who behaved there selves were treated fine. I kissed a hundred girls and some of them two or three times; there was one little girl who I would of liked to take along. She was a little basfull but when she came to me she said I was a pretty nice boy I had one of the boys hold my feet and hung out the window and she loved me something offel [awful].

. . . [T]ell all the boys at home to get into there fighting cloths and be ready to back us up and tell the girls that there is a very important duty for them that is to keep the boys in good humer [humor] and not be stuck up. . .[and] tell everybody that I am on my way and am going to keep going till I get to Berlin.

Pvt. Joseph Reisacker, 356th Infantry, 89th Division

Letter

Dear Folks,

...As to leaving, we hear rumors and rumors and then some more rumors, but I have it directly and on the very best of authority that tonight is the night... All I can say is when letters stop, I've left here.

Private Gerald Keith, 74th Artillery

Letter

Weds. 2nd - Got paid, and left Camp Devens at 2:30 P.M. and finished the day in New York...

Thurs.- 3rd Took ferry at Harlem & got off to go aboard transport -- Hamburg American liner "Amerika." Located in the third bunk from the deck... rotten bed tonight, but the first one in 28 hours.

Fri.- 4th Pulled out of dock at 2:30 P.M. and lost sight of lights at 9 P.M. Lt. Morris & Sgt. Lawrence worked hard to get us fed and did very well. No lights or smoking on deck.

Sgt. Edwin Bemis, 29th Engineers

Diary

|

| Onboard Ship |

On July 15th, we started our voyage, at 7 am, on the transport Northern Pacific. The first day was quite thrilling with the destroyers dashing around us and a dirigible balloon and seaplane above.

But the second day -- wow ! Sick isn't a strong enough word. There were [also] a bunch of negro engineers on board from the deep south, a new experience for me.

Our convoy left us and our boat and the sister ship, Great Northern, were hitting it along at a great rate. I was called upon to furnish two shifts or reliefs of twenty-four men each for watch guard. From then on to the end of the trip I was busy day and night, roosting reliefs and on the watch for submarines. At nite we slept on the deck and the guard was fortunate as the poor fellows who were sleeping below nearly suffocated. I got sick whenever I went below, but felt OK while I was on deck.

Sgt. Edwin Gerth, 51st Artillery

Diary

...At 1:15 PM the alarm bells sounded while we were attending a lecture. We hurried to our berth compartments as the guns boomed, and then on deck. The sub was a porpoise.

Pvt. Otis E. Briggs, 1st Division

Unpublished manuscript, A COMMON SOLDIER

|

| Arrival Over There |

About 2:30 in the morning we entered Havre, France. The cries and shouts of greeting of the boatmen and boatgirls woke us up. We gathered by the rail and gazed for the first time at the brilliantly lighted harbor and realized that we were in France. We could distinguish many shouts of Le Americaine out of the hubbub of French that was shouted at us.

At ten in the morning while we were waiting on deck with our full equipment on, a trainload of 500 wounded came in on the wharf beside us. They were brought on board at once. About half of them were suffering from gas poisoning. Their skin was yellow and their eyes were protected from the sun by paper shades. Many had both legs amputated. A few were Germans who were put in the lowest ward below the water line. The harbor was jammed with warships, transports and hydro aeroplanes.

We marched two miles to a British rest camp. We passed hundreds of German prisoners being marched to and fro from work. They were a dirty hard looking lot. They all examined us minutely and I would have given a lot to know what they thought.

Pvt. Hazen S. Helmrich

Base Hospital 17

|

| Red Cross Canteen, Somewhere in France |

About dusk we got into Chalons sur Marne... We left men on the train while we got off and attempted to inquire at the station where the American headquarters were. The French looked very blank for a while and then suddenly had an inspiration. "Ah, oui," they said, "les dames Americaines", and to our great surprise took us into a large waiting room where the American Red Cross had been running a canteen for two years... They served [us] chocolate, soup and little crackers.

Lt. Birge M. Clark, Balloon Observation Corps.

Unpublished manuscript, WORLD WAR I MEMOIRS

Mother -

There are so many women [in France] wearing black and the other [women] show what a strain they have been thru. There are scarcely any young men seen except those who have returned minus some part of their anatomy or else in such a physical condition that they are almost helpless. All the men working are over fifty and then there are lots of boys...

Pvt. Allan Neil, USMC, 2nd Division

Letter

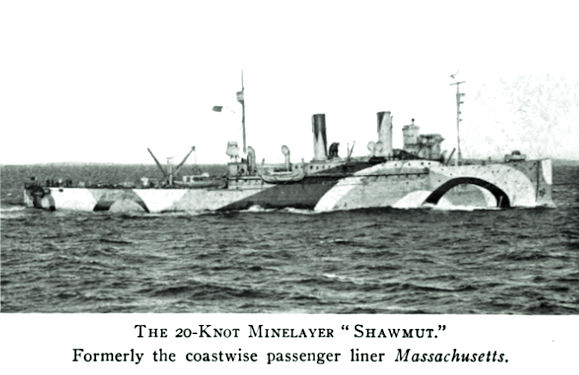

Before the United States entered World War I in April 1917, German U-boats sunk more than 880,000 tons of shipping—a wartime peak that reduced British grain stores to a six weeks’ supply. The success of these U-boats threatened the arrival of American forces in Europe and the Allied ability to maintain supply lines and the movement of troops. To combat this, American naval leaders encouraged convoy and escort systems at sea. While this proved a significant deterrent to enemy submarines, some British and American naval leaders felt this wasn’t enough.

Before the United States entered World War I in April 1917, German U-boats sunk more than 880,000 tons of shipping—a wartime peak that reduced British grain stores to a six weeks’ supply. The success of these U-boats threatened the arrival of American forces in Europe and the Allied ability to maintain supply lines and the movement of troops. To combat this, American naval leaders encouraged convoy and escort systems at sea. While this proved a significant deterrent to enemy submarines, some British and American naval leaders felt this wasn’t enough.