|

| Bill Slim, A Soldier's Soldier, in World War II |

By James Patton

Field Marshal the Right Honorable William J. Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, (1891–1970), KG GCB GCMG GCVO GBE DSO MC PC, who much preferred to be known simply as "Bill" Slim, was a British and Indian Army soldier and the 13th Governor-General of Australia (1953–60). His military career spanned 36 years, including both World Wars. He was wounded in action three times, in 1915, 1917, and 1940. In 1948 he was called out of a brief retirement to succeed Viscount Montgomery as the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (1948–52), becoming the first British officer with Indian Army service to be so appointed.

In the beginning, Bill Slim was born to a middle-class family and educated at fee-based schools, finishing at Birmingham’s King Edward’s School (J.R.R. Tolkien was a fellow student).

Due to family business reverses, university was well beyond his means. Between 1910 and 1914 he taught in a primary school and worked as a foreman in a testing gang at an engineering works.

Although he was never a student at Birmingham University, in 1912 he was allowed to join their Officers Training Corps, which was affiliated with the 5th (Territorial) Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment. Due to his completing this course, he would ultimately be commissioned as a temporary 2nd Lieutenant in the 9th (Service) Battalion of the same regiment, a "K-1 New Army" formation, upon its creation on 22 August 1914.

|

| Cap Badge of Slim's WWI Regiment |

Some have disputed this story, but in 1945 Slim told a reporter that he “began at the bottom of the ladder” as a private in the 5th. On 4 August 1914, the 5th was at summer camp, and Slim with a lance-corporal stripe. A few days later, however, he was busted for allowing his section to take a drink on a long, hot and dusty march. A few weeks later, however, his commission and the transfer to the 9th came through.

In his book The Story of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, C.L. Kingsford tells what happened next:

On June 17, the 9th Royal Warwickshire, under Lieut.-Colonel C. H. Palmer, embarked at Avonmouth, and reached Mudros, in the island of Lemnos, on July 9. Four days later they landed on Beach V, near Cape Helles, where the ship 'River Clyde', from which a part of the immortal 29th Division had disembarked, still lay. For a fortnight they served off and on in the trenches, losing their colonel, who was shot by a sniper on July 25. Colonel Palmer had raised and trained the battalion, which owed much of its fighting spirit and efficiency to his unselfish enthusiasm and ability. A few days previously Lieut. Grundy had been killed, and Lieut. J. Cattanach (the doctor) mortally wounded. Of other ranks 9 were killed and 28 wounded. On July 29 the battalion returned to Lemnos, and on August 3 embarked again for Anzac Cove, where they were to take part in the impending great attack.

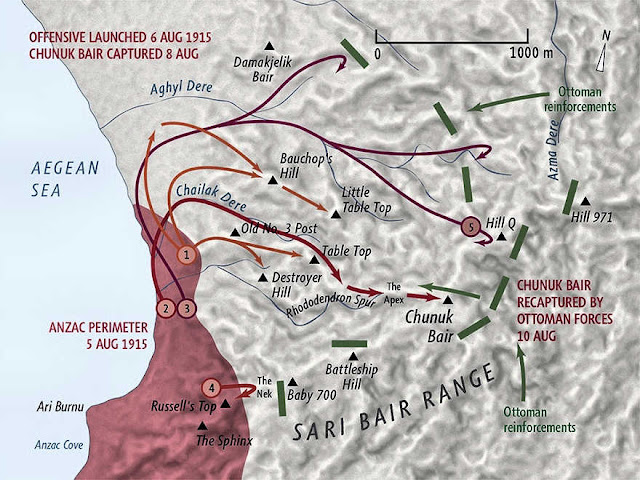

Sir lan Hamilton's plan was to endeavour to gain the heights of Koja Chemen (or Hill 971) and the seaward ridges by an advance from Anzac Cove, simultaneously with a new landing to be made further north at Suvla Bay. The whole ridge, of which Koja Chemen is the highest point, is called Sari Bair. Underneath it on the north lies a long spur known as Rhododendron Ridge, below which a wide water course, split into two forks, both called Aghyl Dere, leads up to Koja Chemen. The 9th Royal Warwickshire, under Major W. A. Gordon, landed in the early morning of August 4. During the first two days (August 6-7) of the attack they were in divisional reserve, but advanced up Aghyl Dere. On August 8 they crossed Bauchop's Hill to the ridge beyond, part going to relieve the 9th Worcester at the head of Aghyl Dere. The New Zealanders had captured Rhododendron Ridge on the previous day…

The main attack came on August 9 with the assault of Koja Chemen. Elements of three battalions- the 9th Royal Warwickshire, the 6th South Lancashire, and the 1/6th Gurkhas- reached the crest, whence they could look down on the waters of the Dardanelles and seemed to have victory in their grasp.

Click on Map to Enlarge

|

| Note Location of Hills Q and 971 |

This capture of heights at Sari Bair would mark the furthest point of Allied advance during the campaign. As part of the force detailed to capture Hill Q (Koja Chemen), 2nd Lieut. Slim, leading around 50 men, was attached to the command of Lieut. Col. Cecil Allanson DSO (1877–1943), of the 1/ 6th Gurkha Rifles, who was himself wounded in the assault. Slim was shot through the chest, suffering serious injury which would affect him for the rest of his life.

But the [Australians] on the right, through no fault of their own, were running late, and when the Turks counterattacked [led by Col. Mustafa Kamal], the assault battalions were forced back to the lower slope trenches. One company of the 9th Royal Warwickshire held on, till they were surrounded, and, as it is supposed, all perished. [This account doesn’t mention the friendly fire incident that required Allanson to move his men away from the downward slope of the ridge].

When at night the 9th Royal Warwickshire was withdrawn to reserve, no officers and only 248 men were left. Major Gordon had been wounded on 8 August, and Major A. G. Sharpe, who succeeded him, was killed two days after. During the four days five officers were killed, 9 wounded and one missing; of other ranks, 57 were killed, 227 wounded, and 117 missing. For their service on these days Majors Gordon and C. C. R. Nevill received the DSO.

The fact that the battalion had lost all its officers, [including 2nd Lieut. Slim], probably helps explain why at the time its share in reaching the crest of Sari Bair was not recorded. As for Bill Slim, he was successfully evacuated and ended up on a hospital ship bound for England and a long recuperation.

The Great War — Mesopotamia

The 9th was transferred to the trenches at Suvla Bay until 19 December, when they were withdrawn to Mudros. On 6 January 1916, they were rushed to Cape Helles to fend off the last Turkish attack, then evacuated three days later straight to Port Said, where they remained until dispatched to Mesopotamia on 12 February 1916 to join the Tigris Corps.

While convalescing in England, Slim accepted a proffered regular commission as a second lieutenant in the under-strength West India Regiment, the 2nd battalion of which was then serving in East Africa. Eventually, however, he cleared his medical boards in September 1916 and instead got himself named a replacement to the 9th in Mesopotamia.

|

| Key sites of the Mesopotamian Campaign |

As a part of Lieut. Gen. Stanley Maude’s (1864–1917) column late in that year, Slim and the 9th served in the capture of the Hai Salient, the capture of Dahra Bend and the Passage of the Diyala. On 4 March 1917, Slim was promoted to lieutenant, then made a temporary captain. The 9th was one of the first British units into Baghdad on 11 March 1917. They then joined Lieut. Gen Sir W.R. Marshall’s column and pushed north across modern-day Iraq, fighting at Delli’Abbas and Nahr Khalis. Crossing the ‘Adhaim and the fight at Shatt al ‘Adheim, Slim was wounded in the arm in late 1917 and evacuated to a hospital in Shimla, India. He was awarded the Military Cross on 7 February 1918 for his actions in Mesopotamia. Subsequent to his departure, the 9th was in action in the Second and Third Battles of Jabal Hamrin and then at Tuz Khurmathl in April 1918. In May 1918, they were attached to the North Persia Force, which found itself in Transcaspia (modern-day Turkmenistan) at the Armistice. Meanwhile, Slim was still in Shimla. For pay reasons, he had been provisionally transferred to the Indian Army, and he was made a temporary major in the 6th Gurkha Rifles on 2 November 1918. On 22 May 1919, he was permanently transferred to the Indian Army and made a permanent captain.

The Second World War — Southeast Asia

During the Second World War, Slim would lead the British 14th Army, the so-called "forgotten army" in the Southeast Asia Theater. With a peak fighting strength of 606,149 men (87 percent of whom were Indian soldiers), this juggernaut was the largest single Army (an Army is a group of more than one Corps) in British history. They fought in the jungles of Burma, kept the Ledo Road lifeline to China open and stopped the last Japanese offensive of the war at Kohima and Imphal in 1944.

Some have considered Slim to be the greatest British general of WWII, or even since the Duke of Marlborough. Historian and journalist Max Hastings has written of Slim: “In contrast to almost every other outstanding commander of the war, Slim was a disarmingly normal human being, … without pretension, devoted to his … family and the Indian Army. His calm, robust style of leadership and concern for the interests of his men, ... his blunt honesty, lack of bombast and unwillingness to play courtier did him few favours in the corridors of power.”

In the 1930s, in order pay for his children’s education, Slim wrote novels, short stories, and other publications under the pen name Anthony Mills, an activity which was proscribed by Indian Army rules. Later, he wrote a personal narrative entitled Defeat into Victory. First published in 1956, it has never been out of print. The prolific author John Lee Masters, an ex-Gurkha officer who had served under Slim in Burmese jungles, said that it proved that Slim was “an expert soldier and an expert writer.”

After Slim’s own autobiography, the next work about Slim was Ronald Lewin’s Slim: The Standardbearer (1977). Following Robert Lyman’s Bill Slim: Leadership, Strategy, Conflict (2011) there has been an outpouring of works on the subject including F.A. Baillergeon’s Field Marshal William Slim and the Power of Leadership (2012), Edward Egan’s Field Marshal William Slim: the Great General and the Breaking of the Glass Ceiling (2015), John Douglas’s Slim: Unofficial History (2016), and Russell Miller’s Uncle Bill. The Authorised Biography of Field Marshal Viscount Slim (2016). All of these works are available today.

Today there stands a life-size statue of Slim erected in 1990 in Whitehall, opposite the Ministry of Defense.

Slim was a good source of quotable remarks. Here are two examples:

I have commanded every kind of formation from a section upwards to this army, which happens to be the largest single one in the world. I tell you this simply that you shall realize I know what I am talking about. I understand the British soldier because I have been one.

The fighting capacity of every unit is based upon the faith of soldiers in their leaders; that discipline begins with the officer and spreads downward from him to the soldier; that genuine comradeship in arms is achieved when all ranks do more than is required of them. “There are no bad soldiers, only bad officers,” is what Napoleon said, and though that great man uttered some foolish phrases, this is not one.

Sources include The Burma Star Memorial, the War Time Memories Project and Rootsweb.com

If we'd had Slim with us, I wonder how Vietnam would have turned out. Just a thought. ---- Dick Coe

ReplyDelete