Le Journal des Tranchées

|

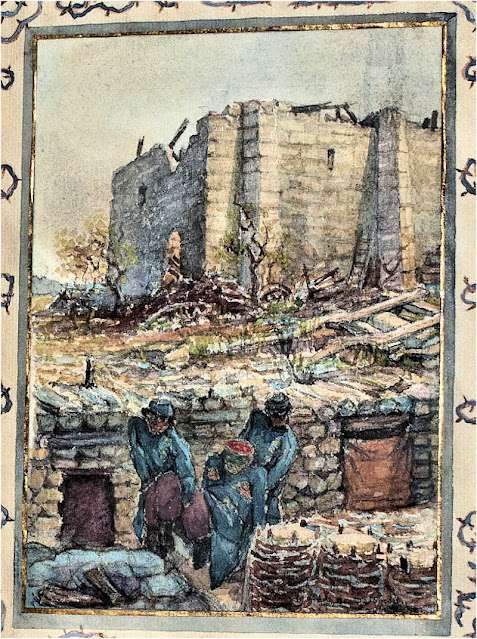

| Working on Trench Defenses |

By John Anzalone

French historian Laurent Gervereau notes the paradox inherent in the fact that soldier-artists seeking to bear witness to their war service often resorted to images that represented a quiet, humdrum war, without reference to real combat. In his record of his year and a half of front line service, Maréchal most frequently refers to simple experiences that readers of soldier memoirs will quickly recognize. He is hungry, always. He sleeps poorly and never enough. When not bored by the tedium of war, he confronts grave danger and fear, always with a quiet stoicism. Rarely moved to high emotion he speaks about violence and death in the matter of fact way of those for whom it has become a fact of life, and his text is accordingly discrete.

But violence and death loom large and when they do appear in the narrative, Maréchal’s very reticence rises to an unusually resonant form of understatement. Here are two examples. In his first encounter with the enemy, there is the terse account of the cadaver of a dead soldier (identified as Old Mayer in the watercolor's inscription below) first seen under a walnut tree then buried the next day.

|

| The Corpse Under the Old Walnut Tree |

The ruins give off a charred odor. And there’s another, more horrid smell, that of the corpses of those who were the first to fall, the soldiers of the 92nd. They are all around us, one in particular near the great walnut tree at the farm near Carmoye: he must have been on lookout behind that tree, but a bullet took him down. He fell with his backpack still on and his rifle in his convulsed hands. The poor devil is swollen and blue, with flies buzzing around him. In the fields that spread out behind us, we can see here and there splotches as red as poppies: the bodies of the dead, in their red trousers.

9th October, Friday night—at nightfall we are ordered to collect the bodies of two soldiers of the 92nd. One is the man under the big walnut tree, the other lies in the road just out in front of our trench. This is one of the most unpleasant chores. … We take all the pains in the world to load the bodies onto the stretchers using poles; given their advanced state of decay nobody wants to touch the corpses with their hands. Burial pits dug ahead of time receive the dead, all of them fully equipped—backpack, bayonet, cartridge belt around their mid-sections. We couldn’t take anything off of them because they were so bloated. I can still hear the sound—the metallic clatter—they made when they landed in their final resting place.

The text relies for its evocative effect on color and sound: first the touches of red—that of the traditional “rouge garance” trousers—that help Maréchal discern the location of many more dead soldiers strewn across the fields; and then the metallic clatter the still fully equipped, bloated body makes as it is dropped into the makeshift grave.

A second episode recounts the death during an artillery bombardment of a soldier named Salomon:

|

| Site of Salomon's Death |

Once the bombardment is over, after 24 blasts and two double-blasts (I had time to count them), Boudon arrives; on his way to us he noticed the body of a comrade killed in a small dugout that had been gutted by a shell. He goes back to get a few men to help free the body of the unfortunate Salomon. The somber procession arrives, advancing clumsily down the narrow trench.

From far away I see a big red stain; the closer they get, the more the dreadful spectacle becomes clear. As they crowd in I manage to see the appalling scene close up. The whole top of the head has been sliced off horizontally just at the level of the eyebrows and the ears, as if with a saw. The inside of this poor head is completely empty and looks like the bottom of a red bowl! The face is completely blue, its deep creases filled with dust. The eyes are closed from the explosion.

I will never forget this spectacle, this poor face masking such emptiness…a pitiful mask and a gruesome image of war.

My comrade Wasseux, one of those who bore his body back, did something remarkably sensitive. He removed his long blue scarf and wrapped Salomon’s head in it, an act of decency to hide the horror.

|

| Never Pass—Engraving at the Quarry by a French Soldier |

This account too concludes with the similarly vivid details of a long blue scarf used to hide the horrific spectacle of the blood-stained, empty skull. Poignant details of this kind are scattered throughout the text; like shrapnel fragments, they tear holes in the “relative quiet” of quotidian routine. Maréchal possesses above all the ability to bring his written narrative alive in the interplay of the narrative and the watercolors. These were executed on the spot fulfilling a goal he had set himself when he was mobilized:

Compelled by the urge to draw, I brought along a small box of watercolors, pencils and a paintbrush. They made the entire Campaign with me and I never regretted having taken them; they allowed me to record my memories and gave substance to my notes by more accurately translating their spirit. What little I saw I described in writing, then I drew what I saw.

|

| Sentry |

Images then, are no mere accompaniment to the journal—they are its raison d’être. Maréchal sees his war as a series of pictures, in terms of colors, of moments, and especially of place, space and volume. Except for one extraordinary page in the manuscript devoted to mates from his unit, of whom he provides a set of expressive vignette portraits, individuals are usually seen from a distance, without identifiable physical or facial traits.

Nor are there depictions of actual combat: the closest we come to a scene of warfare is in one of the nocturnal scenes at which Maréchal excels: the posing of a defensive wire structure known as a cheval de frise athwart a trench at the dramatic moment when a German flare has gone up.

The majority of the drawings are of places, and these are rendered with such fidelity that local historians in the region of Montigny have been able to identify their exact locations, and to reconstruct from them Maréchal’s precise itinerary across the Oise sector until early 1916 when the manuscript abruptly comes to an end. The Machemontoise society now offers tours of that itinerary.

Next: In Part III of this series, to be presented on 4 April 2025, the aftermath of Maréchal's war service will be examined.

Part I of this series can be found HERE.

3 April 25 NEWS! The entire manuscript of Journal Des Tranchées can now be viewed online HERE (in 4 sections) thanks to JSTOR.org.

About Our Contributor

John Anzalone is Professor of French and Media/Film Studies, Emeritus, at the Department of World Languages and Literatures, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY

Contact John at: janzalon@skidmore.edu

Fascinating details about memory and representation. The quiet scenes seem to me filled with longing and regret.

ReplyDelete