On 1 July 1918, at 7:10 p.m., a catastrophic explosion tore through the National Shell Filling Factory at Chilwell, Nottinghamshire. The blast killed 134 workers and injured 250—the biggest loss of life from a single accidental explosion during the First World War. [This comment overlooks the Halifax ship explosion of 1917 in which nearly 2,000 died.] Eight tons of TNT had detonated without warning, flattening large parts of the plant and damaging properties within a three mile area. The colossal blast was heard 30 miles away. Eyewitness, Lottie Martin, a worker at the factory, later recalled: "…Men, women and young people burnt, practically all their clothing burnt, torn and disheveled. Their faces black and charred, some bleeding with limbs torn off, eyes, and hair literally gone…" Rapid action by the Works Manager, Arthur Bristowe—who tipped burning TNT from conveyor belt trays—prevented a further 15 tons of TNT being detonated by the spreading fires. In under half an hour, the fires were under control and emergency services from across the region were arriving.

Despite the workers’ extreme shock and the terrible destruction, repairs were swiftly carried out overnight enabling some of the next morning’s day-shift to start work again. The Home Office Committee of Enquiry published its report into the explosion on 7 August 1918. The police undertook a separate investigation into suspected sabotage. Neither enquiry could conclusively identify the cause of the explosion. The vast factory, which covered 194 acres (78 hectares), and eventually had 7,500 workers, was set up by Viscount Godfrey Chetwynd at the instigation of David Lloyd George, then head of the newly formed Ministry of Munitions.

Chetwynd, who came from the automobile industry, had no prior experience of explosives production. He was a maverick and self-publicist who loathed red tape. He demanded, and got, a free hand to design and create the factory without bureaucratic interference. Chetwynd chose the site at Chilwell because it had good rail and road links, was conveniently located between the raw material producers of the north and the supply ports of the south and could draw on the under-employed workers of the local textile industries.

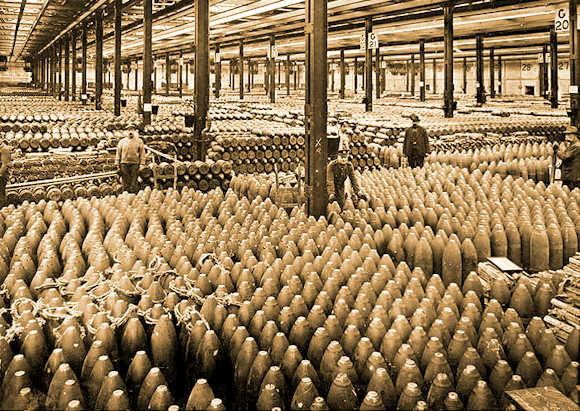

Against convention, he adapted existing machinery—for coal crushing, stone pulverising, sugar sifting—to prepare the ingredients for making TNT. In keeping with his individualist nature, Chetwynd literally stamped his mark on the factory with the distinctive, self-devised crossed Cs of the Chilwell crest, adding the Royal Crown to imply a royal association with the government-owned factory. Within a few months of the factory’s opening, it had filled a major proportion of the large-calibre shells used during the Battle of the Somme (1 July to 18 November 1916). On the first day alone 250,000 shells were fired by British guns. Women made up a large part of the workforce at the Chilwell factory. They were nicknamed "canaries", as handling TNT could stain skin yellow. Some even gave birth to yellow babies.

Toxic jaundice was dangerous, and 106 women died from it during the course of the war. As the potentially lethal effects of filling high-explosive shells became better understood, munitions workers were issued with overalls, masks and caps to mitigate the dangers, along with washing facilities and good food Despite the devastation of the explosion, the Chilwell factory became the most productive shell filling factory of the war. Just two months after the fatal blast, the factory filled 275,327 shells in one week,—a record number. By the end of the war it had produced more than 19 million shells—over half the total British shells fired on the Western Front—along with thousands of mines and bombs.

|

| Memorial at the Site of the Detonation |

Of the 134 dead, 25 were women. Only 32 of the fatalities could be positively identified. The victims were buried in a series of mass graves at the parish church, a short distance from the factory complex.

Source: Historic England, June 2018; British War Works Tokens

You might consider the Halifax explosion of 1917 when declaring worst disasters of WW1; which eclipses Chilwell by a very long shot!

ReplyDelete