|

| Going to War with the Lebel Rifle |

James Patton

The French rifle Model 1886 M93, universally known as the Lebel Rifle, was the first of a series of revolutionary designs whose firepower changed infantry tactics forever going forward. The Lebel had a ten-shot capacity, featured a "small" 8mm bore (the rifle that it replaced was 11mm) and it used a revolutionary smokeless, high velocity, flat trajectory cartridge. In the arms race of the day it was followed by the Russian Moisin-Nagant in 1891, the British Lee-Enfield and the Austrian Mannlicher in 1895, the German Mauser in 1898, and the U.S. Springfield in 1903 (which is a licensed version of the Mauser). Among these, the Lebel proved to be a durable weapon that stood up well under the field conditions of WWI.

The task of developing a new rifle and cartridge was given to the ad-hoc Commission de Ármes a Répetition ("commission for repeating arms") led by General Baptiste Tramond (1834–1889), who was the commandant of the military college at Saint Cyr and an avid marksman. It was comprised of the Inspecteur de Manufacture Nationale d’Armes de Châtelleraut Col. Basil Gras (1836–1901), the designer of the previous rifle, the Model 1874, the Commandant de l’Ecole Normale de Tir at the Camp de Châlons Lt. Col. Nicolas Lebel (1838–1891), the Directeur de la Pouderie du Bouchet Col. Jules François Marie Bonnet (1840–1928), Col. Pierre Jean Castan (1817–1892), Chef du Service de Armes Portatives se la Section Technique de l’Artillerie Col. de Tristan, Capt. Désaleux and Paul Marie Eugene Vielle (1854–1934) from the Laboratoire Central des Poudres et Salpetres, the inventor (1884) of nitrocellulose-based propellants.

The new rifle was designed at the Chatellerault state armory by Bonnet and Gras with the help of a civilian named M. Verdin. Lebel developed the flat-nosed metal jacketed bullet for the new 8x50 mm cartridge. Initially his name was only attached to this bullet rather than its official title “Balle M,” but later his name stuck to entire system, most probably because Lebel oversaw the firing trials of the new rifle.

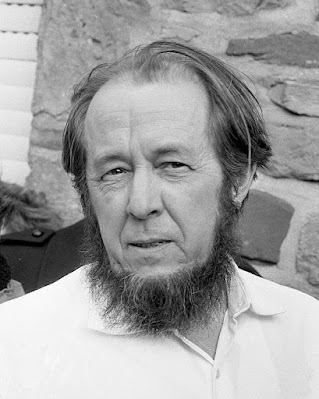

The Lebel has a manually operated, rotary bolt action, with a multi-part bolt that has a head that is attached to the body by a cross screw. When locked in firing position, the bolt is horizontal to the receiver, differing from the Mauser and others, where the locked bolt is snug against the stock. The feed is from a tubular magazine, located below the barrel and protected by the wooden fore stock. The cartridges are moved from the magazine to the loading position by a swinging lifter, operated by the bolt. There is a magazine cutoff on the right side of the action, which when engaged blocks the loader and turns the rifle into a single-shot. The magazine capacity is eight rounds, plus two additional rounds can be carried in the rifle—one in the chamber and one in loading position in the lifter. The combination "iron" sights included a fixed "combat" blade for 250 meters range and tangent-type adjustments for ranges between 400 and 800 meters. For ranges between 800 and 2000 meters, the rear sight has to be elevated.

|

| Breech Detail |

The Lebel rifle had a grenade launching system, called the Tromblon Vivien-Bessières (or “VB”), which entered service in 1916, invented, as its name implies, by Messrs. Jean Vivien and Calix Gustave Bessières (1881–1942). The grenade was cylindrical in shape with a circular central channel. To fire it, the grenade was placed in a cup-like device attached to the end of the barrel and the rifle was placed with its butt on the ground, canted at the appropriate angle, and, using a live round, the gun was fired. The grenade was expelled by the force of the explosion, the bullet traveling through the central channel where it hit a metal striker, which in turn set off the detonator igniting the fuse.

The range of the VB was around 150 meters and the fuse delay was five to eight seconds. It was quite effective—one of the best setups of its type used during the war. Versions of the VB were adapted for use with the American M1903 Springfield and M1917 Enfield rifles.

The Lebel had drawbacks, particularly when compared to its rivals:

The tubular magazine was hard to reload—the others had box magazines which could be recharged by using stripper clips.

The tubular magazine added weight to the barrel which changed with every shot fired.

The sights were hard to align and subject to damage from careless handling.

The cartridge was 50mm long, compared to the Mauser’s 57mm or the Springfield’s 63mm. Thus, the size of the charge was smaller and so the muzzle velocity was lower. Because the Lebel had a tubular magazine, the length of the cartridge affected the capacity of the magazine—with a 57mm cartridge the magazine could have held only seven.

There was no manual safety. Soldiers were taught that the rifle would always be carried with no round in the chamber (thus reducing the combat load to nine bullets).

Field-stripping was more difficult because the Lebel required a screwdriver.

The receiver was a medium slab-sided milling which was more time-consuming to machine and added weight to the rifle as compared to its contemporaries.

Due to the size of the receiver, the Lebel used a two-piece stock, so the top of the barrel was completely exposed – in rapid fire the user could be burned by the hot barrel.

With minor modifications, the Lebel rifle served with the French army and its colonial forces until WWII, and the three-shot carbine version was used up to the Algerian War of 1960. In 1916 the reorganized Serbian army was equipped with the Lebel when they were serving alongside the French at Salonika. During the WWI era three manufacturers produced more than 2.5 million rifles. In 1968 I could’ve bought one at an estate sale in Ardsley, NY for $15. Today Lebels in firing condition list for around $1,500 on the internet. Should’ve bought it.