|

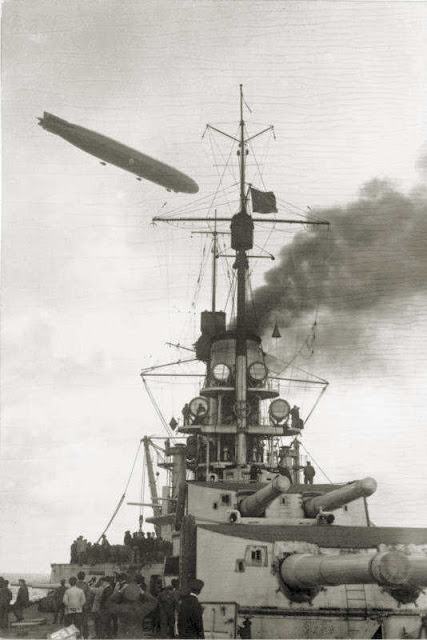

| A Naval Dirigible Flies Over a German Battleship During Operation ALBION |

By Richard Dinardo, USMC University

For far too long, the eastern front in World War I has remained, in Winston Churchill’s words, “the unknown war.” Despite the best efforts of Dennis Showalter, Holger Herwig, Norman Stone, and others, the course of affairs in the east is still largely a blank slate, especially in the period between Tannenberg and the Russian revolutions. This article will attempt to address this gap by covering German air operations on the eastern front, focusing in particular on operation ALBION, mounted to seize the Baltic islands of Oesel, Moon and Dagö in October 1917. [The original article also addressed the 1916 campaign in Rumania.]

After the Romanian campaign, the scene of action on the eastern front shifted to the north, specifically to the Baltic. With Russia crumbling internally, OHL sought advanced positions from which to launch a possible thrust at Petrograd. The most notable of these was Riga, which General Oskar von Hutier’s Eighth Army seized on 1 September 1917, using the tactics that would later bear his name.

In order to make Riga useful both logistically and as a naval base for light forces, however, it was necessary to occupy the islands of Oesel, Moon and Dagö, which controlled access to and from the Gulf of Riga. Both OHL (in reality, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff) and the head of the German Admiralty’s staff, Admiral Henning von Holtzendorf, agreed on 13 August 1917 to undertake the operation against the islands after the capture of Riga.

The invasion force would consist of some 300 ships, including ten of the Navy’s newest battleships, wrested away from Admiral Reinhard Scheer’s High Seas Fleet by the German Admiralty. The landing itself would be left to the XXIII Reserve Corps, in effect the heavily reinforced 42nd Infantry Division plus some corps-level assets, a total of about 24,000 men.

Supporting these forces would be Army Captain Holtzman’s 16th Air Detachment (6 aircraft) and Detachment Baerens (8 seaplanes and the seaplane tender St. Elena, commanded by Navy Lieutenant Baerens). The Navy also committed six zeppelins (ranging from the older L 30, L 37, LZ 113, and LZ 120, to the newer SL 8 and SL 20) to the operation. Also supporting the operation were aircraft detachments at Windau and Libau. Calculating the number of aircraft involved in the operation is difficult, as the numbers vary. One source gives the number of aircraft (not including zeppelins) as 101, although the total number of operational aircraft available on any one day of the operation probably did not exceed 65. Aside from Holtzman’s unit, all of the aircraft (regardless of service) and zeppelins came under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, the commander of the 2nd Scout Group.

|

| Operation ALBION |

Despite their small numbers, aircraft undertook a variety of roles before and during ALBION. As always, the first of these was reconnaissance. Aircraft tried to provide information on the dispositions of the Russian garrison on the island, as well as those Russian Navy units positioned in Moon Sound that might threaten the invasion force. German aircraft and zeppelins were also used to bomb various parts of the island, with varying degrees of success. Under no circumstances, however, were German aircraft to drop bombs near the landing sites, especially Tagga Bay, the principal landing area. It was feared that any kind of bombing attacks against the Russians there would tip them off as to the location of the landing sites, thus forfeiting the element of surprise.

Weather severely hindered the ability of aircraft to make much of an impact on the operation. On the day of the landing, for example, weather precluded any kind of activity by the zeppelins. Just as worrisome for the zeppelins was the increasing shortage of hydrogen gas. The Baltic Airship Detachment had to use a mixture of air and hydrogen, which increased the risk of fire. This danger eventually caught up with the Germans on 16 October 1917, when L 37 returned to its base at Seerappen having sustained heavy damage in a mid-air fire after a bombing mission.

Fixed wing aircraft also suffered at the hands of the weather. Just as zeppelins were grounded on 12 October 1917, weather limited German aerial coverage of the landings to a pair of artillery spotter aircraft and one bomber during the first hour of the landing, followed in the second hour by one bomber and one reconnaissance plane. The 42nd Infantry Division regarded this as completely inadequate. On the 13th, rain and snow precluded effective reconnaissance flights, and although three seaplanes did make brave attempts at flying reconnaissance, two of the three aircraft were damaged upon landing, killing Naval Lieutenant Anton Priemes.

|

| The Gotha WD-11 Torpedo Bomber Proved Unsuccessful During the Naval Battle |

Despite the adverse conditions, aircraft did make some positive contributions to the conduct of ALBION. Aircraft operated with infantry units as “infantry aircraft,” as prescribed by German doctrine at the time. When the weather allowed, these aircraft did conduct a number of reconnaissance missions. When the breakdown of wireless radio communications prevented passing the information to the ground forces via radio, pilots resorted to the time-honored back up method of tying messages to strips of cloth and then dropping them next to the units. At times this procedure involved aircraft having to fly through Russian ground fire several times. Aircraft would also “lead” infantry columns, circling around and then flying off in the direction the infantry was supposed to march.

The Germans were certainly fortunate that Russian air opposition during ALBION was negligible, although Russian anti-aircraft fire could pose problems for planes. The only known Russian air activity was on 14 October, when a German naval aircraft was attacked by three Russian Nieuports. When Holtzman’s 16th Air Detachment moved to an airfield next to Oesel’s largest town, Arensburg, all they found were four Nieuports the Russians had destroyed and abandoned

What insights can we draw from these operations? The first thing we can draw from the air operations described here is that although they were on a far smaller scale than those on the western front, they nonetheless illustrate nearly the full scope of flexibility inherent in airpower. With the exceptions of air superiority and the then still nascent concepts of aerial re-supply and rescue, German aircraft in [ALBION] undertook every other kind of operation associated with air warfare. In addition, the Germans took advantage of the relatively benign conditions in the east as an opportunity to test newly fielded aircraft, especially bombers.

Much of the German air effort was spent flying reconnaissance. . . Although ALBION did not require much in the way of bombing, German aircraft undertook a large number of reconnaissance missions, although success in these varied considerably, partly because of the weather, but also for other reasons that will be discussed momentarily. The most intriguing aspect of airpower here was the use of aircraft as a means of communications, particularly as a replacement for wireless radio.

|

| An aerial view of Arensburg (Kuressaare) flying station on the island of Osel (Saaremaa) The hangars were destroyed by bombs dropped by a German flying boat, October 1917. |

The German expectation was that the majority of wireless radio message traffic, both land and naval, would be handled through the wireless radio station aboard the invasion force’s flagship, the battle cruiser Moltke. Once collected, information would then be passed on to General von Hutier, the overall commander, who was at his headquarters in Libau. In some cases individual aircraft were tied into specific ships by wireless radio for purposes of artillery spotting. In addition, a system of colored ground signals and signal flares was set up to facilitate communications between aircraft and ground troops.

Actual experience showed many of these expectations to have been overly optimistic. To be sure, there were instances when the combination of aircraft and wireless radio paid dividends, such as when the aircraft spotting for the torpedo boat G-104 was able to provide the information needed for the boat to knock out a Russian field battery. Too often, however, radio communications were simply overwhelmed by the sheer volume of traffic. With some 300 ships to command, not to mention Army traffic, the Moltke’s wireless radio station was quickly overloaded. This also applied to the command ships of the sub-elements of the invading force. Some of the Army’s after-action reports noted the need for the Army to establish its own communications system as rapidly as possible once the ground forces were ashore. German air doctrine stressed this for the air forces as well, even before ALBION was undertaken.

The communications problems described above severely impacted German air operations in ALBION. Even when zeppelins were able to fly reconnaissance and bombing missions, the overloaded wireless radio communications prevented the immediate reporting of their results, thus rendering the information gained useless. This applied to fixed wing aircraft as well. Fixed wing aircraft did have the alternatives of either dropping written messages on the units they were supporting, or literally landing by the headquarters of the units and delivering the information personally. Given the difficult weather and at times unsuitable ground on Oesel, however, the latter method increased the chances of aircraft suffering damage when landing, as occurred a few times during the operation. Nonetheless, the combination of airpower and wireless communication held great promise for the future.

|

| Infantry Heading for Shore—ALBION Was the Most Successful Amphibious Operation of the War |

One aspect of operations in general the Germans should have brought away from this experience concerned joint operations. One of the senior German naval commanders in the Baltic, Rear Admiral Albert Hopman, wrote to his wife on 19 September 1917 that “our army commanders have no idea of naval warfare.” The reverse was true in ALBION at the lower levels, at least in terms of the support provided to the Army by naval aircraft. The 42nd Division’s after-action report on the operation complained that many of the reconnaissance reports from naval aircraft were either inaccurate or simply false, owing to the fact that naval aviators were unfamiliar with land warfare. The report also called for Army and Navy pilots to be trained for joint operations. . .

In this case, the Germans generally failed to learn from ALBION. . . Organizationally, [for the next war] one thing the Germans should have brought away from ALBION was the need for a robust naval air arm. . . For the Germans, however, the idea of a strong naval air arm never came to fruition. Although plans for German naval expansion did call for the building of an aircraft carrier, the projected Graf Zeppelin, it never reached completion. Nor did Germany’s top naval commander, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, consider the aircraft carrier to be anything more than a prestigious adjunct to the battleship.

Source: "From Bucharest to the Baltic German Air Operations on the Eastern Front, 1916-1917," Chronicles Online Journal, Air University, 2007

Very interesting dive into a fascinating campaign.

ReplyDelete