From: "Ernst Jünger: Our Prophet of Anarchy"

Originally Presented in Unherd of The Post

By Aris Roussubis

|

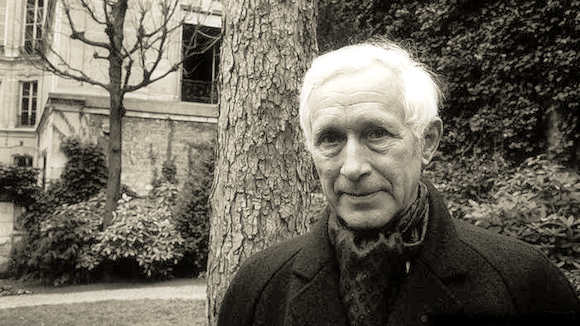

| Ernst Jünger in Paris, 1941 |

It sounds like Jünger's second World War may have been as dangerous for him as his first when he was wounded 14 times. MH

With its modern themes of detachment and alienation, the recent revival of Ernst Jünger’s early work by the internet dissident Right is an understandable urge. When I was a younger man, Jünger’s Storm of Steel, his hallucinatory account of his experiences as a stormtrooper commander in the trenches, was, like Malaparte’s Kaputt and Graves’s Goodbye to All That, a major formative experience in my desire to experience war and, callow though it now sounds, prove myself in it.

Perhaps it’s natural, then, that in later life, the sombre reflections of the middle-aged Jünger as expressed in his recently translated wartime diaries, a husband and father disenchanted with the modern world around him, now seem so compelling.

The diaries open in 1941, with the 46-year-old Jünger serving in an administrative capacity on the general staff of the German army occupying Paris. Initially feted by the Nazi party for the proto-Fascist tone of his early works, Jünger publicly rejected the regime’s advances and came under suspicion as a result, his house searched by the Gestapo and the threat of persecution always hanging over him. A central figure in Germany’s interwar conservative revolution, Jünger, who stated he “hated democracy like the plague,” had come to despise the Nazi regime at least as much. Ultimately, he was far too rightwing to accept Nazism.

Jünger’s intellectual circle had aimed to transcend liberal democracy through fusing Soviet Bolshevism with Prussian militarism, yet the illiberal regime that actually came to power was wholly repugnant to him. “The Munich version—the shallowest of them all—has now succeeded,” he wrote, “and it has done so in the shoddiest possible way,” filling him with dread that Hitler would drive Germany and Europe toward disaster and discredit radical alternatives to liberalism for generations to come.

Jünger’s two closest friends, the National Bolshevik Ernst Nieckish and the philosopher of law Carl Schmitt, each met different fates under the new Nazi order: Nieckish jailed as a dissident until his liberation by the Red Army in 1945 and Schmitt as the regime’s foremost legal theorist. Jünger remained friends with both. For Jünger, the internal exile, dissidence would come in the veiled form of his dreamlike novella On the Marble Cliffs, published on the cusp of war in 1939, in which he predicted the disaster and bloodshed the Nazis would bring in their train. Carefully monitored and shunted off to a desk job in France, Jünger spent his war as a flâneur along the quais of Paris, buying antiquarian books, conducting numerous love affairs, and recording his impressions of the city he loved.

|

| Ernst Jünger at 100 |

A feted intellectual, and a lifelong Francophile, he befriended the city’s cultural elite, socialising with Cocteau and Picasso as well as the collaborationist French leadership and literary figures such as the anti-Semitic novelist Céline, a monster who “spoke of his consternation, his astonishment, at the fact that we soldiers were not shooting, hanging, and exterminating the Jews—astonishment that anyone who had a bayonet was not making unrestrained use of it”. For Jünger, Céline represented the very worst type of radical intellectual: “People with such natures could be recognised earlier, in eras when faith could still be tested. Nowadays they hide under the cloak of ideas.”

While listening to Céline’s ravings about Jews with polite horror, Jünger was embroiled in an affair with Sophie Ravoux, a German-Jewish doctor, and helping to conceal other Jews in hiding, as well as warning the French resistance about imminent deportations. He records the first reports of mass executions in the east, shared among the army leadership, initially with disbelief and then with horror, disgust, and shame. Generals back from the east recount meetings with figures like “a horrifying young man, formerly an art teacher, who boasted about commanding a death squad in Lithuania… where they butchered untold numbers of people,” or share third-hand rumors about “men who have single-handedly slain enough people to populate a midsize city. Such reports extinguish the colours of the day. You want to close your eyes to them, but it is important to view them like a physician examining a wound.”

Continue reading the article HERE.

No comments:

Post a Comment