|

| John Galsworthy (1867–1933) |

With the outbreak of World War I, the novelist and playwright John Galsworthy, best known for The Forsythe Saga and for later receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature, was a strong supporter of the war in 1914 and considered the invasion of Belgium an outrage against an innocent nation. His attitude about the war shifted as he experienced it. During the First World War he worked in a hospital in France as an orderly, after being passed over for military service, and in 1917 turned down a knighthood, for which he was nominated by Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

By this time, Galsworthy was struggling to comprehend its "monstrous calamity and evil" and to decide what his further role in the war effort should be. He confided to his diary that "the heart searchings of this War are terrible. . .I think and think what is my duty."' For the next four years, Galsworthy tried to answer this question. The mangled and immobilized bodies he had seen on the front and wer returning home seemed to mock his conviction that the Allies were fighting a war to defend freedom and played powerfully on his imagination and conscience.

In the spring of 1918, he finally found a way to reconcile his hatred for war with his duty to serve his country: he agreed to edit a small journal for the Ministry of Pensions about and for disabled soldiers, Recalled to Life, which he renamed Reveille. He would use it to awaken the nation to its obligations to the war wounded.

|

| First Issue |

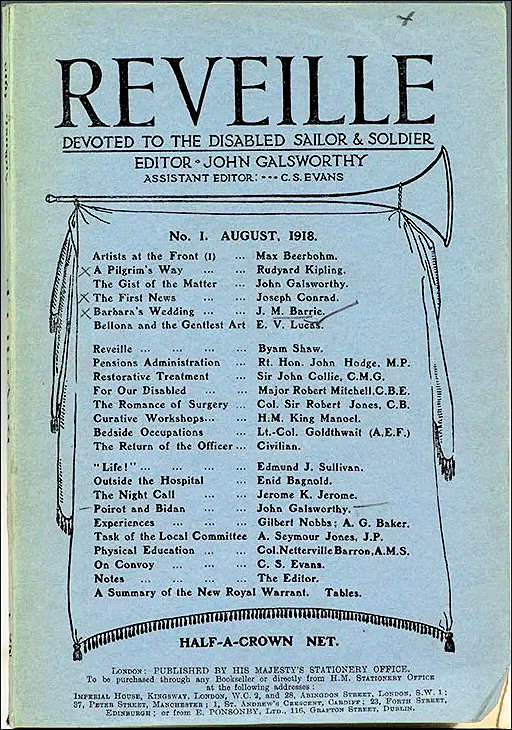

Granted complete editorial liberty (or so he believed) and generous funding by the ministry, Galsworthy was determined that Reveille would be no mere mouthpiece to disseminate reassuring platitudes. In addition to soliciting articles by experts on disability, he enlisted an extraordinary array of artistic talent and transformed the publication of an obscure technical journal on military orthopedics and disability pensions into a minor literary event. Contributors included Max Beerbohm, Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad, J.M. Barrie, Enid Bagnold, and Jerome K. Jerome.

Galsworthy's passionate introductory editorial is perhaps the journal's most remarkable document, not the least because of its bleak candor at a time when the war's outcome was still uncertain. He observed:

In every Street, on every road and village-green we meet them-crippled, half crippled, or showing little outward trace, though none the less secretly deprived of health. Those who encouraged such men to "drift" into shiftless despair were "guilty of ingratitude, and will be the first to show impatience and heartlessness, when, five or ten years hence, we see him cumbering the ground, hopeless and embittered, often out of work, and always an eyesore to a nation which will wish to forget there ever was this war.

For Galsworthy, the fate of Britain's disabled war veterans was linked to the intertwined politics of remembering and forgetting the war itself. He keenly appreciated the fact that the maimed bodies of countless soldiers signified the ambiguities of the end of war for victors and losers alike or, rather, that the official cessation of hostilities between nations did not coincide with the end of war's consequences for its victims.

|

| A Photo from an Issue of Reveille |

In what proved to be the last issue of Reveille, Galsworthy returned to these themes.

The State, like the humblest citizen, cannot have it both ways. If it talks-as talk it does, with the mouth of every public man who speaks on this subject-of heroes, and of doing all it can for them, then it must not cheese-pare as well, for that makes it ridiculous. Britain has climbed the high moral horse-as usual-over the great question of our disabled; she cannot stay in that saddle if she rides like a slippery lawyer.

It is not difficult to understand why many officials at the Ministry had grown uncomfortable with their celebrated editor. With the signing of the armistice and mounting pressure of censorship by ministry officials on him, Galsworthy resigned his duties, and the journal closed down. Yet, Galsworthy's words were prophetic of developments in the 1920s and 1930s.

Sources: Adopted from "John Galsworthy and Reveille," by Susan Neeson in the February 2006 St. Mihiel Trip-Wire, which included excerpts from: "Remembering and Dismemberment: Crippled Children, Wounded Soldier, and the Great War in Great Britain," by Seth Koven from American Historical Review, October, 1994

Fascinating story. He was nearly 50 in 1914 and still wanted to go.

ReplyDeleteWhat a literary lineup in that first issue!