Corrected Text, 20 May 2014

[Editor's Note: Regular reviewer Jane Mattisson Ekstam will be examining works on the topics of pacifisim and conscientious objectors in her next several pieces. To start the series, she will provide some background on these general topics here on the eve of her first review.]

[Editor's Note: Regular reviewer Jane Mattisson Ekstam will be examining works on the topics of pacifisim and conscientious objectors in her next several pieces. To start the series, she will provide some background on these general topics here on the eve of her first review.]

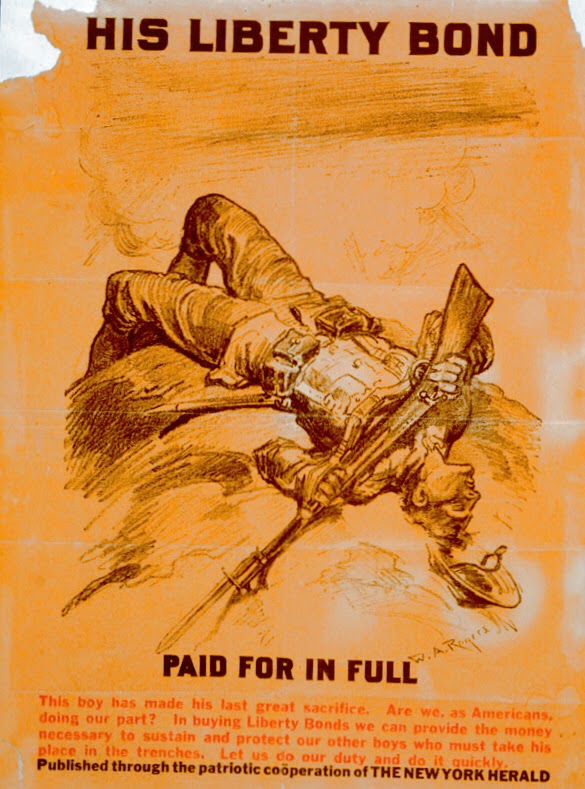

Conscientious objectors, or "conchies" as they were sometimes called, took the Lord's commandments at face

value. At a time when so many answered Lord Kitchener’s exhortation "Your

Country Needs You," many asked themselves, "Who were the pacifists, and why

were they held in prison and threatened with execution?" In total, there were approximately 16,300

British conscientious objectors in World War One, of whom 6000 served

varying sentences in prison. Thirteen hundred of the 6000, labeled "absolutists",

refused to compromise with the state in any shape or form.

|

| A Tribunal for British Conscientious Objectors |

As war fever hit the streets in 1914,

conscientious objection was regarded as both unpatriotic and cowardly. While

many conscientious objectors served as non-combatants in the trenches and were

prepared to die, they were unarmed and refused to handle munitions; as a

result, they risked being shackled to the wheels of a gun carriage or hung on

barbed wire. According to author Adam Hothschild, almost 50 conscientious objectors were shipped to France for possible execution for refusing to fight. Hothschild does not claim, however, that they were executed. [The original version of this article suggested that the 50 men were executed. We apologize for publishing this error. MH] And in 1916, just before the

Battle of the Somme, a group of war opponents at a British camp nearby refused

to bear arms. Threatened with the death sentence, they stood their ground. It

was only thanks to last-minute lobbying in London that their lives were spared.

Few at the time understood what it meant to be a conscientious objector.

Conscientious objection existed not

only in Great Britain but also in Germany and America. At the beginning of the war, for example, a handful of German parliamentarians opposed war credits.

Radicals like Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht later went to prison, as did

the American socialist leader Eugene V. Debs. Conscientious objection was

international and was here to stay. Indeed, as Will Ellsworth-Jones has noted, "the battle over conscience fought between 1914 and 1918 laid the groundwork

for the treatment of the conscientious objector both in the Second World War

and in the wars that have followed in Vietnam and Iraq." (We Will Not Fight. The Untold

Story of the First World War’s Conscientious Objectors. Aurum, 2008).

|

| COs Sentence to Work in a Quarry near Dartmoor Prison |

While historians have tended to

focus on combatants, histories of the conscientious objectors are relatively

rare. A few historians, like Felicity Goodall, are trying to correct the

balance, arguing:

To

stand against the tide of public opinion armed only with your beliefs; to be

divided from friends, family and even spouses by those beliefs; to be isolated

from the defining experience of your generation. Few people have the courage

not to follow the common herd. (We

Will Not Go to War. Conscientious Objection During the World Wars. The History Press, 2010)

The story of the conscientious

objector is a noble one. It involves people, events, and moral testing grounds

that are, as Adam Hochschild argues, "more revealing than any but the greatest

of novelists could invent." (To End All Wars. A Story of Protest and Patriots in the First World

War. Macmillan, 2011)

I will review all three books cited

here for Roads in the coming months, along with one novel, Edward Marston’s Instrument of Slaughter (2012), a riveting

tale about a group of conscientious objectors in London in 1916. My series of reviews begins tomorrow with Will

Ellsworth-Jones’s We

Will Not Fight: The Untold Story of the First World War’s Conscientious

Objectors.