Voices from the Front: An Oral History of the Great War

by Peter Hart

Oxford University Press, 2016

Peter Hart is oral historian with the Imperial War Museum (IWM). In that capacity he interviewed 183 British Great War veterans in the 1980s and 1990s, at a time when their numbers were quickly diminishing. Because the interviews took place more than 65 years after the end of the war, it's not surprising that quite a few of the men were under-age enlistees, with a few enlisting as young as 15. In this book, Hart's interviews are augmented by others conducted by fellow oral historians at the IWM and by interviews conducted by the British Broadcasting Corporation in the 1960s.

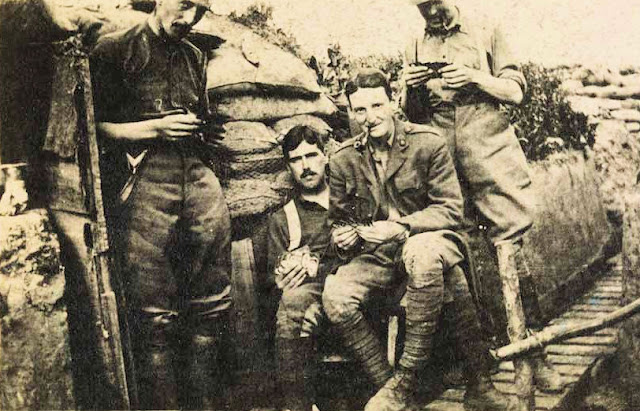

In his introduction Hart outlines the advantages of oral history. He is not, of course, unmindful of the limitations of oral history. Because of some of these limitations, oral history is often more valuable in learning what it was like to be a soldier in the war, versus presenting an accurate account of events. How did the soldier feel when he enlisted and went through training? What did it feel like to advance to the front and, finally, to go "over the top?" What did the soldiers carry into battle? How was life in the trenches? Oral history can help us answer these questions.

Hart's chronological narrative serves as the framework onto which he hangs the interviews. This arrangement is interspersed with digressions to cover the war in the Middle East ("nightmarish" does not begin to do it justice), the naval war, the air war, life in the trenches (my favorite chapter), and the aftermath of war. This layout serves Hart's purpose well; his proportions of narrative versus oral history are appropriate because he wants to concentrate on the men's experience in the overall context of the war.

A sampling of the interviews illustrates events that, more than 60 years later, still left impressions on the veterans.

Of course, most of the men were octogenarians or nonagenarians when they were interviewed. When one considers what Private Alex Thompson of 2nd King's Own Scottish Borderers, experienced at Ypres in 1915, one wonders how any of these men survived at all: "I'd got an explosive bullet in the left arm, it split my left arm…another bullet just above my wrist did for my thumb—it cut the sinews. Then I got another one in this side—a shell burst—shrapnel. I got a hole here in the lefthand side of the stomach and that was running with blood. Shrapnel in the shoulder up here. All in seconds, all in a bunch one after the other. I was knocked right upside down" (p. 70).

Engine Room Artificer Ernest Amis, HMS Kent, described his ship's sinking of the German cruiser Köln: "Our last salvoes fired into her at about 400 yards range. She was on fire. Some of them [German sailors] were jumping into the water on bits of wreckage so as to try and get to us, but the seas were icy cold. The sea was not calm then; it was a choppy sea…We tried to save some, we hauled some aboard, but they were too numb; they eventually died and we simply put them back into the drink again. There was no time for any ceremony. We didn't know whether there would be any other German ship about ..." (p. 164).

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, serving ashore near Gallipoli, recalled a young sailor named Horton going to the aid of a fellow sailor who had been wounded: "...a bullet struck him dead centre of the brow, went clean through his head and took a bit out of my knuckle. Poor old Horton. He kept crying for his mother. I can see him now. Hear him at this very moment. He said he was 18, but I don't think he was 16, never mind 18" (p. 99).

Of course there's humor here, too. Private Harold Hayward, 12th Gloucestershire Regiment, was wounded in the scrotum and hospitalized. A well-meaning female visitor persisted in asking Hayward about the nature and location of his wound. Hayward's final answer to her is priceless. And Corporal Donald Price, 20th Royal Fusiliers, developed a bad boil on his inner thigh. His description of a medical officer's examination of him while in muddy, slimy trenches is evidence that funny episodes can happen in horrible circumstances.

There are no photographs, illustrations, or maps in the book and, frankly, they are not needed.

I have some limited experience in oral history (Italian American World War II veterans), and this is the kind of thing that is valuable and important. It is a pity that more historians and institutions did not think to collect interviews with Great War veterans until it was almost too late. Thankfully, Hart and the IWM preserved these voices for us and future generations.

by Peter Belmonte

Hart's chronological narrative serves as the framework onto which he hangs the interviews. This arrangement is interspersed with digressions to cover the war in the Middle East ("nightmarish" does not begin to do it justice), the naval war, the air war, life in the trenches (my favorite chapter), and the aftermath of war. This layout serves Hart's purpose well; his proportions of narrative versus oral history are appropriate because he wants to concentrate on the men's experience in the overall context of the war.

Order Now |

Of course, most of the men were octogenarians or nonagenarians when they were interviewed. When one considers what Private Alex Thompson of 2nd King's Own Scottish Borderers, experienced at Ypres in 1915, one wonders how any of these men survived at all: "I'd got an explosive bullet in the left arm, it split my left arm…another bullet just above my wrist did for my thumb—it cut the sinews. Then I got another one in this side—a shell burst—shrapnel. I got a hole here in the lefthand side of the stomach and that was running with blood. Shrapnel in the shoulder up here. All in seconds, all in a bunch one after the other. I was knocked right upside down" (p. 70).

Engine Room Artificer Ernest Amis, HMS Kent, described his ship's sinking of the German cruiser Köln: "Our last salvoes fired into her at about 400 yards range. She was on fire. Some of them [German sailors] were jumping into the water on bits of wreckage so as to try and get to us, but the seas were icy cold. The sea was not calm then; it was a choppy sea…We tried to save some, we hauled some aboard, but they were too numb; they eventually died and we simply put them back into the drink again. There was no time for any ceremony. We didn't know whether there would be any other German ship about ..." (p. 164).

Ordinary Seaman Joe Murray, serving ashore near Gallipoli, recalled a young sailor named Horton going to the aid of a fellow sailor who had been wounded: "...a bullet struck him dead centre of the brow, went clean through his head and took a bit out of my knuckle. Poor old Horton. He kept crying for his mother. I can see him now. Hear him at this very moment. He said he was 18, but I don't think he was 16, never mind 18" (p. 99).

There are no photographs, illustrations, or maps in the book and, frankly, they are not needed.

I have some limited experience in oral history (Italian American World War II veterans), and this is the kind of thing that is valuable and important. It is a pity that more historians and institutions did not think to collect interviews with Great War veterans until it was almost too late. Thankfully, Hart and the IWM preserved these voices for us and future generations.

by Peter Belmonte

I am somewhat mystified by the ships in the naval battle mentioned here.

ReplyDeleteSMS Koln was sunk at the battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914, but as far as I can tell HMS Kent was not involved; Koln was sunk by battlecruisers. Kent played a major role in the battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December that year, and she sank SMS Nurnberg. The description that the veteran ERA Amis gives matches the sinking of Nurnberg - some German sailors being pulled on board but most dying soon afterwards.

Did Amis make a mistake and Hart not check it, or did Belmonte make a typo?

You'll find errors like that in oral history. It's part of the charm. As the review says, you don't read oral history for the facts but for the emotions.

DeleteAnother great book of oral history is Veterans: Last Voices of the Great War by Richard van Emden. The wonderful old guy who was still working and driving at the age of 108 will be in my memory for life.

ReplyDeleteAdrian and Tom, I rechecked the information, and it is indeed as posted above. And, as stated, such is oral history. Also, the crew member is identified as being on the HMS Kent, but it's possible that he was on a different ship during the sinking of the Koln and transferred to the Kent later.

ReplyDeletePete

If you are interested in seeing men "in person" talk of their experiences, I highly recommend the documentary "The Last Voices of WWI". It is deeply touching to see the emotion in their faces as they talk about the war. My grandfather served at Meuse-Argonne and passed away two years before I was born. I'd like to think I know him just a bit through these men's stories.

ReplyDelete